We need to measure the impact of complex service changes to understand if they have made any difference or not. This will help maximise benefits for patients and minimise costs, Liz Mear and colleagues write

Take two services to reduce admissions for frail elderly people. Both are promising initiatives.

One is developed locally but fails to attract longer term investment and support. Another is enthusiastically adopted by word of mouth across the region and beyond, with support from charismatic champions.

But without some form of assessment, it is hard to know which will really deliver and how to generalise from local successes.

‘We need to understand the ways in which care can be organised to maximise quality and minimise costs’

This is a time of rapid change. The health and care system is becoming more complex, with new models of care spanning traditional boundaries and sectors. Managers and clinical leaders need to make fast decisions on service configurations or remodelling within economic constraints.

The NHS Five Year Forward View sets out clearly the case for major system innovations and ways of working. It suggests that future innovation gains are likely to come as much from changes in process and service delivery as technological “fixes”.

We need to understand better the ways in which care can be organised to maximise quality and minimise costs.

There is a spectrum of effort. For small, local changes careful measurement may be enough.

More complex system-wide changes may need carefully controlled evaluations, to generate useful learning for others.

In this country, we now have an embedded infrastructure through the National Institute for Health Research of active partnership and collaboration between service providers and researchers via Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs), academic health science networks and similar developments in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

We have a range of methods and resources to evaluate the pressing problems and potential solutions of complex health and care systems in the 21st century.

Key messages

- Without trying to measure the impact of changes, we will never know which ways of organising services will be most helpful in maximising benefits for patients and minimising costs.

- Researchers can help service leaders clarify goals, gather relevant evidence and identify appropriate methods to assess service changes, local or national

The pressing need for evaluation

There is a real appetite among service managers for evidence and understanding of evaluation to inform practice and decision making.

Courses offered recently by NIHR CLAHRC North Thames to service leaders on the purposes and approaches to evaluation have been consistently oversubscribed.

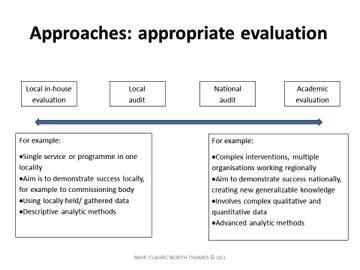

There are a range of evaluation approaches and effort, depending on need and purpose. This is summarised in Figure 1 (see above).

In the continuum of evaluation effort, being clear about who needs the evaluation and why, should help to decide what kind of assessment is needed. For smaller scale changes, local audit may provide “good enough” evidence that changes were in line with the original goals.

At the other extreme, the NIHR is funding an ambitious three year ‘‘alongside-evaluation” costing over £1m of the system-wide Salford integrated care hub. This is a complex research programme, following particular populations over time to assess interventions such as motivational health coaching for people with multiple morbidities.

It should provide powerful evidence to other health and care systems integrating services.

For all planned changes, services need to think about:

- the aim of the changes;

- who the key stakeholders are;

- what is known already from evidence and other service experience;

- what could and should be measured – activity, costs, outcomes;

- possible bias and what could be done to reduce this;

- combining findings from different sources; and

- sharing findings with others.

Scenario: What would a ‘good enough’ evaluation look like?

A service manager is planning to introduce a new out of hours palliative care service. This was prompted by a serious incident and a series of patient complaints around fragmented care.

Working with a local university, the service lead clarifies the main goals of the changes: to improve access (especially to pain relief services) and continuity of care, without increasing costs.

A quick scoping review of published and grey literature, suggests a range of models in use. A public health trainee identifies some schemes in neighbouring localities, including skilling up community nurses by the specialist palliative care team.

Other information comes from the network of palliative care nurses. An operational researcher runs a series of “what if” models to simulate impact of different options on the whole system.

This set up period helps identify key goals of the change and what might be measured (for instance, the presence of advance care plans was seen as a useful process quality marker for end of life care). The researcher helps the service lead to identify the population, available sources of information (from GP registers, quality and outcomes framework and Clinical Practice Research Datalink information through to hospital episode statistics and other data) for baseline measures and to think about measures of success.

Stakeholder interviews are planned with palliative care doctors and nurses, community nurses, GPs and families and carers before and after service changes.

How can we get the most from service evaluations?

In order to make impact, studies may need to produce ongoing findings. For instance, the NIHR funded evaluation of stroke configuration services in London and Manchester published important interim findings which influenced further investment decisions at one of the sites (data on additional lives saved making the case for more radical centralisation of services in Manchester).

Researchers need to understand the pressures and priorities of those delivering services. New approaches, including forms of participatory research, are welcome developments.

‘Social media provides a new range of platforms’

We know that managers tend to place greater emphasis on personal experience and stories of good practice from other sites than formal sources of evidence.

We also know from evidence of the importance of opinion leaders in sharing learning. Social media provides a new range of platforms to add context and commentary to research findings.

It is important that services and evaluators identify target audiences and stakeholders at the beginning of a project.

Bodies like AHSNs and CLAHRCs and equivalents in Wales and Scotland can provide useful networks and banks for completed evaluations to share practice, as well as advice on evaluation approach and partnering with researchers.

Conclusions

There is a real appetite among service leaders and managers to assess the impact of changes and to learn from others. For large scale changes, independently funded research can provide learning at a national scale.

But that is not always needed.

For smaller changes, local research and simple measurement is good enough. Researchers can help by working with service leaders to articulate goals, identify key stakeholders, bring together relevant evidence, identify methods and measures of impact and consider best ways of sharing results.

Without trying to measure the impact of changes, we will never know which ways of organising services will be most helpful in maximising benefits for patients and minimising costs.

Liz Mear is chief executive of North West Coast Academic Health Science Network; Naomi Fulop is professor of healthcare organisation and management at the University College London; and Tara Lamont is scientific adviser for NIHR’s health services and delivery research programme

1 Readers' comment