It is time for a major change in end of life care services, to move care and resources away from hospitals towards community-based alternatives, writes Phil McCarvill

The challenges for the health and social care system in our rapidly ageing society and the pressure associated with ongoing public spending constraints are clear for all to see.

Faced with these twin challenges, we can either stand by and oversee a gradual decline in the quality of care provided or we can seize the opportunity to fundamentally change the way we do things. Our task is to find new ways to deliver better care for a greater number of people with fewer resources.

‘We know what people who are dying and their families want; there is surely an onus on us to strive to meet their wishes’

Marie Curie’s latest report, Death and Dying: Understanding the data, argues that by examining how the health and social care system can meet the needs of people who are dying, we can learn a lot about the future scope and focus of other services. It says that in order to break with the current overreliance on hospitals in caring for people in the last weeks of life, we need to improve end of life care in all health and social care settings.

the research pulls together much of what we have learnt about end of life care in England over recent years. It presents data that has previously been published elsewhere, such as in the VOICES survey of bereaved people and data from the National End of Life Intelligence Network. It supplements what we already know about death and dying.

Most people who are terminally ill say that they would prefer to die somewhere other than in hospital. We also know from a National Audit Office report in 2008 that many of those who die in hospital do not have a medical reason to be there: “Forty per cent of patients who died in hospital in October 2007 did not have medical needs which required them to be treated in hospital, and nearly a quarter of these had been in hospital for over a month.”

Aligning needs with resources

The clear message to emerge from Death and Dying is that hospitals are not the best places to care for people who are dying. The VOICES survey, which collated the views of people who had recently lost a relative, found that there were very different experiences of care depending on whether the deceased person had died in a hospital, hospice, care home or their own home.

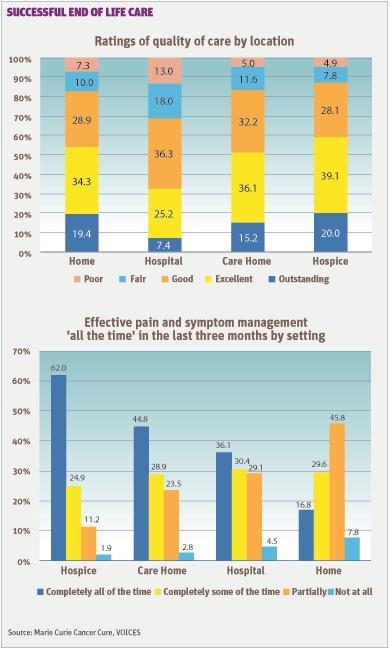

Hospitals scored worst across almost all measures. The following table from the Marie Curie report shows the significant differences in perceptions of care between different settings: 32.6 per cent of respondents whose loved one died in hospital said the care was excellent or outstanding, compared to 53.7 per cent at home, 51.3 per cent for care homes and 59.1 per cent for hospices.

This picture is concerning because the majority of people continue to die in hospitals. This prompts the question − is it possible to align the wishes and needs of patients with available resources so that we provide the care that people who are dying really want? We believe it is, but to do so we will have to improve the quality of care across all health and social care settings.

The growing evidence base should give us the confidence to shift resources away from hospital care to community-based services in care homes, hospices and people’s own houses. We know what people who are dying and their families want; there is surely an onus on us to strive to meet their wishes.

‘Home and community-based services can help to reduce hospital use significantly. This is undoubtedly good for the NHS budget and patients’

Two reports from the Nuffield Trust have explored experiences of end of life care. Understanding patterns of health and social care at the end of life mapped the use of health and social care services at the end of life across different age groups and conditions. It concludes that we need a more mature debate about the balance between health and social care services:

“The interaction between hospital and social care costs at the end of life prompts questions about the optimal mix of care services, especially given evidence of people’s preferences for where they would like to die.”

The second Nuffield report, which evaluates the impact of the Marie Curie nursing service on place of death and hospital use at the end of life, compares key data relating to service use and outcomes for almost 30,000 Marie Curie nursing patients and a closely matched control group of patients who had not used the service. The report found 77 per cent of those who had used these nursing services died at home, compared to 35 per cent of the control group.

Just 7.7 per cent of Marie Curie patients died in hospitals, compared to 42 per cent of the matched control group. Similarly, people who used Marie Curie nursingservices had much lower emergency admissions at the end of life − 11.7 per cent, compared to 35 per cent. Of Marie Curie patients, 7.9 per cent had used accident and emergency services, compared to 28.7 per cent of the control group.

‘It is not as simple as saying let’s move people out of hospital, we must ensure we develop a whole system approach’

This clearly shows that home and community-based services can help to reduce hospital use significantly. This is undoubtedly good for the NHS budget, but it is also good for individual patients and their families, who can be supported to have the kind of death they want.

A complete approach

However, we must also acknowledge that it is not as simple as saying let’s move people out of hospital, we must also ensure that we develop a whole system approach.

Care homes must think about how they can transfer best practice from those homes which care compassionately for people in the last hours of life to their peers that shift people off to hospital at the first sign of decline.

We need to offer better support for families, carers and volunteers who are pivotal in enabling many people to remain in their own homes.

Organisations that care for people in their own homes must determine why pain management is perceived to be poorest at home.

The following table based on VOICES survey data shows just 16.8 per cent of relatives of those who died at home felt that pain was “managed completely all of the time”.

We must ensure GPs are trained and are confident about working with people who are dying and we explore Clare Gerada’s assessment that the Harold Shipman scandal may have made some GPs reluctant to prescribe at home: “One of the problems is an unintended consequence of the Harold Shipman inquiry. GPs are very reluctant to use heavy-duty analgesics on their patients generally, and also for things that are not malignant, like osteoporosis. We deal with it very badly.”

‘With a little courage and imagination, we can ensure that people at the end of life get the services they require’

As an organisation, we pride ourselves on providing personalised care with excellent pain management, but we also know that there is more to do to convince the public that everyone who chooses to die at home will achieve their goal and will do so in a pain-free way.

Finally, we need to ensure better coordination. Care works best is when we all work together to avoid unnecessary admissions to hospital, ensure rapid discharge for those who do not need to be there and ensure that individuals have the right community-based support available when and where they need it.

So, we know what people want at the end of life, where they wish to die and how we can most effectively support them to exercise genuine choice. A fresh approach to funding and commissioning health and social care can unlock resources which, as the Nuffield Trust has shown, could be better spent on providing decent social care packages and home-based nursing and support to people who are dying.

With a little courage and imagination, we can ensure that people at the end of life get the services they require, in the place of their choice, being pain free and surrounded by the people they love. This will not only benefit patients, but may also enable the wider health and social care system to overcome future challenges.

Phil McCarvill is head of policy at Marie Curie Cancer Care, Phil.McCarvill@mariecurie.org.uk

No comments yet