Determination by key individuals can rally trust staff into dedicating themselves to pressure ulcer prevention. Jennifer Trueland details two successful local campaigns

Case study 1: the SHA

Ruth May admits that it wasn’t easy at first to get senior management on board with an ambitious programme to cut the incidence of pressure ulcers. But the then nurse director for NHS Midlands and East persevered and soon won the support of the executive team at the strategic health authority, and also the chief executives of local primary care trusts.

The result was a campaign that saw a dramatic reduction in prevalence of new grade 2, 3, and 4 pressure ulcers in the Midlands and the East of England − down by 36 per cent between April and October last year.

“I came back from maternity leave in January 2011, and in February reports from the ombudsman hit my desk,” she says, referring to the Care and Compassion report that detailed failings in the care of older people.

“It was heartbreaking − it was really all about basic care, about hydration, about skin. Everything is connected. I decided if we focused on one thing, then it would help the other things, too.”

‘If anyone notices a red area of skin, they actually call out “red alert” and all the staff hurry to the bedside’

Ms May, who is now regional chief nurse, says she did a great deal of talking to her fellow board members and to PCT chiefs to make her case. “I took a lot of stick at first, but they were actually great,” she says, adding that the projected cost savings helped to persuade the finance directors.

Eventually it was agreed that the goal of eliminating all bar grade 1 pressure ulcers would be one of the SHA’s high level ambitions.

Although the SHA made it clear to local trusts that this was a priority area, there was no one-size-fits-all approach. And Ms May confesses she was impressed and moved by the ingenuity shown across the region (see the Luton and Dunstable case study). The SHA board, including the chair, made a point of asking about pressure ulcer prevention when they visited hospitals, she says, and this helped to keep up momentum.

“It got to the point that people were talking to them about pressure ulcer prevention every time they visited,” she laughs. “They would joke that nobody wanted to talk about anything else.”

A deliberate decision was taken to use the NHS Safety Thermometer to measure prevalence, which meant that data was captured from across the whole NHS in the region, not just hospitals.

“It meant that 55,000 patients were being measured every month - that’s a fantastic achievement,” she says.

It was important to realise that by raising awareness, the number of reported pressure ulcers would increase, she adds.

Hearts and minds

Staff buy-in and engagement is also essential, she adds. “Yes, you need executive support, but you also need to get to the hearts and minds of the people delivering the care.”

The SHA also took the innovative step of running a public-facing campaign involving Michael McGrath, who has muscular dystrophy. “We wanted people at risk of getting pressure ulcers - and their families - to know how to prevent them happening, and what to do if they thought they were at risk.”

Mr McGrath, a power-chair user, who has led expeditions to the north and south poles, says he is now “acutely aware” of the risks associated with pressure ulcers, and takes action including checking his skin regularly, moving position as often as he can and ensuring he is properly hydrated.

The campaign made use of patient stories, including a family explaining in their own words how a pressure ulcer had affected them, and also gives access to education tools.

In December 2012, the SHA reported that 574 patients in the Midlands and East had a grade 2,3 or 4 pressure ulcer on prevalence day in October, 1.09 per cent of the 52,570 patients checked. This was down by more than 400 patients since the previous April. In addition, numbers of grade 4 pressure ulcers halved, suggesting that preventative action was helping to stop ulcers worsening.

National moves such as the CQUIN on pressure ulcers help to keep the issue high profile, she says - and she doesn’t see the new commissioning regime post-April 2013 reducing the impetus around pressure ulcer prevention.

“Lots of people have been really brilliant in taking this on,” she says. “It can take bravery to stand up and say what’s right, and our clinical leaders have been fantastic.”

For more detail about the campaign, click here

Case study 2: Luton and Dunstable

On the orthopaedics and trauma ward at Luton and Dunstable University Hospital, there is a system for spotting potential pressure ulcers − and stopping them develop.

If anyone notices a red area of skin on a patient, they call out “red alert” − actually call it out − and all the staff at that end of the ward hurry to the bedside.

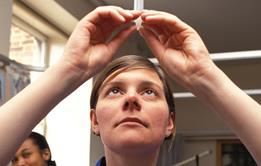

“It’s called ‘see, swarm, solve’,” says tissue viability clinical nurse specialist Sylvia Woods. “Someone sees it, everyone swarms, and then they come up with a plan.”

This is one of the ways in which Luton and Dunstable is endeavouring to eliminate all but the most unavoidable of pressure ulcers. Importantly, the “red alert” is sounded at the earliest possible sign that an ulcer might be about to develop that gives the team a chance to take action to prevent an ulcer forming.

It is clear that Luton and Dunstable responded enthusiastically to the old SHA’s ambition to eliminate grade 2,3 and 4 pressure ulcers (see first case study). Last year, two pilot wards − trauma and orthopaedics and stroke - were chosen to take forward ideas which might help reduce pressure ulcer incidence.

These wards, where patients are frequently elderly and have mobility issues, were deliberately among the most challenging in the trust.

“Yes, these groups have the highest numbers of at-risk groups,” says Ms Woods. “But if it could be done there, it could be done anywhere.”

The preventive measures are all evidence based. “It might involve repositioning the patient more frequently, checking nutrition and hydration, all sorts of things,” she adds.

But the intitiative has also tested inventiveness. The trauma and orthopaedics ward nurses started wearing flashing badges, adapted Blue Peter style from some flashing Christmas ear-rings bought cheaply at the local pound shop. When they are wearing the badges around the hospital, other staff ask what it’s all about.

The stroke ward also put Blue Peter skills to the test, inventing their own form of “turn clocks” − little clocks which have timers set to alert staff to when the patient needs to be repositioned or otherwise checked by the team.

The ideas are intentionally simple and easily understood by patients and relatives as well as staff. “Sometimes I think we over think things,” says Ms Woods. “But it’s about coming up with the simple things - small steps, which really make a difference.”

At the end of the pilot, the orthopaedics ward had managed more than 120 days without a pressure ulcer, while the stroke ward had achieved more than 70.

“They have particularly complex patients, so that was a real achievement,” says Ms Woods. “The whole ward was utterly devastated when one did occur, and everyone was really keen to learn if anything could have been done differently to prevent it.”

Growing attention

Now the trust is rolling out pressure ulcer prevention to all wards, a process that is expected to take around 15 months.

“We’re not being prescriptive about it, because we know that what works in one ward isn’t necessarily the best thing for another. But we’ve got really strong support from the executive team, and real enthusiasm from the staff on the ground, who have been coming up with some great ideas.”

Although not one of the pilot wards, the trust’s short-stay medical admissions unit has also shown great success in tackling pressure ulcer prevention - and managed to go more than 180 days without one. It used a “flip chart” process which clearly showed the number of pressure ulcer-free days, and which could be seen by staff, patients and visitors.

Other wards are looking at using the SSKIN bundle (see main article), and the trust is making use of “safety crosses” to give live, real-time information which is posted on the walls of the ward.

Again it has a hand-crafted element, with days without pressure ulcers shown by a green dot, with red dots to show days where there has been one.

Ms Woods agrees that pressure ulcers have too long been regarded as the bottom of the heap, and is glad that the issue is gaining more high-level attention.

Patient Safety − an HSJ supplement

From better workforce vetting to new approaches to tackling pressure sores, the latest thinking on patient safety

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

New thinking on pressure ulcers: the case studies

- 5

- 6

- 7

No comments yet