The failure of Care.data has been largely blamed on a poor communication strategy, but Paul Cooper says it is equally about people’s rationale about what is acceptable when sharing personal data

The modern day consumer understands that information is power. Facebook, the world’s biggest social networking site, experienced a backlash over the way it allowed affiliate companies to access its members’ details, while Google has seen public trust across Europe fall following a series of recent data breaches.

‘No one discloses sensitive information in a medium over which they have no control’

New technologies are driving the shift towards greater transparency about how consumer information is used. And organisations governing public data come under extensive scrutiny, especially within the sensitive field of healthcare.

As we know, sharing patient information across the NHS is not straightforward. One of the main barriers to success for largescale projects aiming to join up healthcare data is getting the modern day patient on board. The summary care record, HealthSpace and Care.data are prime examples.

- Probe lays bare ‘lapses’ in past patient record procedures

- Patient records supplement: The dataset with no name

- Lord Darzi: Electronic records are the next ‘breakthrough drug’

- Off the page: profiles improve person centred care

Common problem

Patients frequently ask “why isn’t information shared between my providers of care?” or “why am I repeatedly asked the same questions?” But in the same breath, patients express concerns about national systems storing and accessing their medical information.

‘There’s a threshold which customers feel comfortable disclosing sensitive information without sufficient control or trust’

Therein lies a common problem associated with digitising healthcare: patients already expect information to be shared, but upon learning that it is not, they become anxious about the use of national databases for such purposes.

So what is the cognitive rationale behind these attitudes towards patient information, which has led, in part, to the delay of the Care.data scheme?

Control and sensitivity

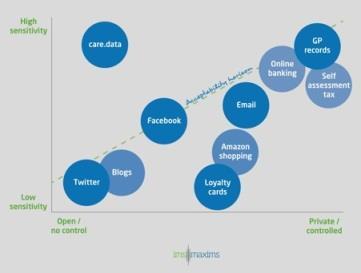

A patient’s willingness to disclose information is about the sensitivity and perceived control or trust in the system in which the information is stored.

Social media tools such as Twitter and blogs are systems that are typically low in sensitivity and low in control; these are wide open and have little or no control over who reads the published content.

‘We have patients wanting a joined up health service, yet they are concerned about the NHS divulging their data’

No one discloses sensitive information in a medium over which they have no control. For example, you would not have a consultation with your doctor using Twitter.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have systems that are high in sensitivity and high in control or trust, including online banking, self-assessment tax returns and discussing medical issues with your GP. These examples include highly sensitive or valuable information, and we are only prepared to share it with a system or person that we control or trust.

Software used for everyday activities generally has low to medium levels of sensitivity. Such systems are trusted or have some degree of control over disclosure to unauthorised third parties.

These include Google learning information from search histories; supermarkets monitoring shopping habits through loyalty cards; or mobile apps accessing information via social media circles such as work, friends and special interests.

The acceptability horizon

There is a threshold for which consumers will feel comfortable disclosing sensitive information without sufficient control or trust: an acceptability horizon.

Below the horizon is using Twitter or discussing a medical condition with a GP, both of which are tolerated in society. However, systems that are introduced above the line are treated with nervousness and suspicion.

‘Patients would store their data somewhere they could control it and which they trust’

The problem facing NHS England is that the summary care record and Care.data are both way above the horizon; both contain sensitive information and patients do not have control over its use or disclosure, despite Care.data being anonymised.

So, referring back to the “common problem”, we have patients wanting a joined up health service, yet they are concerned about the NHS divulging their data. How do we solve this problem?

The ‘acceptability horizon’: how patients perceive data security

Giving back control

It is really very simple. The answer is to transfer responsibility for the electronic patient record from the NHS to patients. This would mean patients would own and control their own health records, granting access to their carers as required. It truly becomes their data, not that of the NHS.

Practically speaking, patients would store their data somewhere they could control it and which they trust – possibly a trusted “cloud health record” which allows data to be accessed simply and securely through mobile apps.

This approach would address the conflict in patient expectations, while bringing the system below the acceptability horizon necessary to succeed.

Paul Cooper is head of research at IMS MAXIMS

1 Readers' comment