Continuing financial upheaval, industrial action taking hold and the implications of reform coming into focus: 2011 has been a tumultuous year. Here, HSJ’s writers reflect on some of the landmark events that defined the year.

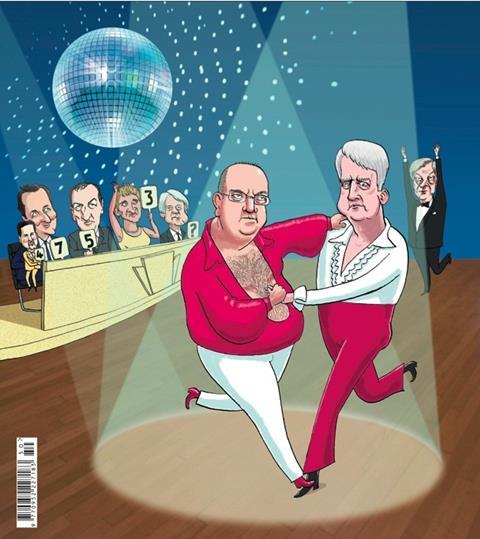

The non-resignation of Andrew Lansley

Arguably the biggest event of 2011 was something that did not happen. Few secretaries of state have experienced a year with more setbacks and survived. The decision not to reshuffle Andrew Lansley was hugely significant.

During the first quarter, the coalition’s leadership crawled all over Mr Lansley’s reforms in an attempt to understand why it was getting such a hard time from so many opponents. They reached the conclusion that dramatic action was needed – but what action? Should they abandon the reforms and ditch its proponent before things got worse or find a way to sell the plans to the public.

In the end the latter won through – but for a while it was touch and go. Mr Lansley wrestled with the humiliation brought about by the pause and considered his position, but he was buoyed by the support of Tory backbenchers and pushed on.

The move to transparency

Ministers made a string of symbolic moves towards a culture of more open data in the NHS, hoping transparency would drive improvement and put patients in charge of their care. The Cabinet Office revealed in July that GP outcome data would be made public, along with prescribing data and information on clinical audit, complaints and staff satisfaction. Next, the GP Extraction Service was announced to link primary and acute care data, enabling patients to be tracked across the entire service for the first time.

And chancellor George Osborne also announced that patients will be given online access to their GP records by the end of this parliament.

The Department of Health’s information strategy spent all of 2011 about three months away from release, a status it still occupies. But the information revolution is ploughing ahead regardless, with the full backing of Number 10.

National pay bargaining reversals

Frustration with ever-rising salary bills spilled over into the first decisive moves away from national pay bargaining. NHS Employers’ attempted attack on the 2004 Agenda for Change pay framework, with its built in yearly pay rises, was rejected by unions. But from sickness pay to increments, foundation trusts have for the first time been using their freedoms to negotiate new terms and conditions.

The more provocative moves are being challenged in court. They come amid wider ministerial concerns about public sector salaries and a desire, expressed in the Health Bill, to even the “playing field” with the private sector. Added to proposals to water down the NHS pension scheme – leading to the first national NHS strike for 23 years in November – and scrap protection for outsourced staff, the changes are contributing to growing staff unrest. If they also result in a reduction to staffing costs – 70 per cent of many trusts’ spending – the consensus from government may be that all the pain was worthwhile. Staff are very likely to disagree.

Goodwill towards public health plans collapses

The government has been accused of making big political mistakes over the Health Bill, but its handling of public health policy might have been worse.

The reason is that while the proposed NHS reforms raised eyebrows from the start, the plan to move public health responsibility onto local authorities was welcomed by both the public health community itself and councils.

But over the past year this goodwill has been squandered, with a procession of stories in HSJ on the draining away of support, because ministers have failed to offer any real detail to back up their rhetoric on the importance of public health. Directors of public health have warned that experienced staff and services are being lost while they remain in the dark about future budgets, workforce and their own status.

July’s public health update and way forward document was supposed to fix the problem, but left most questions unanswered and created yet more.

In September the DH said it was committed to “producing reform updates on five areas during the autumn”. It is now winter and an increasingly cool response may yet become colder.

Confusion for Cambridgeshire commissioners

Cambridgeshire was one of the heartlands of general practice led commissioning. About two years ago, the county’s primary care trust developed advanced plans for delegating what were called “hard budgets” to several enthusiastic groups of practices.

The PCT’s idea – also being pushed regionally by the strategic health authority – was that the groups would operate as fleet of foot social enterprises. Freed of some public sector governance shackles, they would be able to provide some services from themselves – presenting an organisational form that might enable integration.

Andrew Lansley’s commissioning reforms were billed as enhancing such developments, but instead threw them into complete confusion. Now, after 18 months of agonising over statutory structures, the GPs in and around his constituency have decided to form what looks very much like a large PCT.

As they address the technicalities of forming the large clinical commissioning group, they will have to look again at whether they can achieve what was on the table two years ago.

Reconfiguration of Chase Farm Hospital

This reconfiguration appeared a no brainer for a cash-strapped NHS. Chase Farm Hospital is 15 minutes’ drive from two other hospitals and its Victorian main building is a former children’s home, unsuited to modern care.

Just one problem: before the last election Andrew Lansley and David Cameron had visited, pledging to safeguard services. An NHS London-backed reconfiguration plan was blocked by the health secretary in March.

However, in September Mr Lansley accepted the findings of an Independent Reconfiguration Panel report.

Chase Farm will lose its maternity unit, have its accident and emergency department downgraded and split from Barnet Hospital to, in all probability, merge with North Middlesex University Hospital Trust. Chase Farm is not alone. Numerous other district general hospitals face downgrades if the NHS is to save £20bn and centralise services. All to the potential fury of local campaigners and MPs.

The death of the national programme for IT

In September, it emerged that the National programme for IT was to be scrapped. The programme, if it had a voice, might have replied that reports of its death were greatly exaggerated.

The story stemmed from the Cabinet Office’s Major Projects Authority, which said NPfIT had not, and could not, deliver its original intent. The DH would therefore speed up its existing plans to dismantle the programme and set up a new partnership with Intellect, the technology trade association, to explore ways to stimulate the supplier market.

So the national programme is not quite dead but staggers on – albeit with yet another knife in its back. And some big questions remain, not least how the DH and major supplier CSC will solve contractual issues and whether trusts will have money to buy their own systems.

The AHSC model re-imagined

December’s innovation review put academic health science centres back in the news, after April saw the original model collapse. The stepping down of Imperial College Healthcare Trust chief executive Steve Smith with no foundation trust application in sight and a £40m predicted deficit for 2011-12 was seen as a defeat of the centralised form of AHSC.

The other four AHSCs had adopted a federated model, allowing more autonomy to their member trusts.

Professor Smith published what was effectively a resignation letter in the trust’s plan for reaching FT status. He said “overdependence on the acute sector, underdevelopment of primary care and dispersal of specialist services” had left the trust financially unviable.

Whatever the cause, the revamped Imperial offering, headed by Lord Darzi, abandons the old model and with it the only attempt to create a centralised academic health centre to rival US giants.

Big names at the Mid Staffordshire public inquiry

Whether it was NHS chief executive David Nicholson calling for the power to renationalise foundation trusts, in direct opposition to health secretary Andrew Lansley, or a Care Quality Commission officer describing her superiors’ evidence as “aspirational”, the public inquiry has been nothing if not controversial.

There were denials from former health ministers Andy Burnham and Ben Bradshaw that there was political pressure to push unsuitable trusts to foundation status. There have also been confessions: chief nurse Dame Christine Beasley admitted nursing had lost its way, while the trust’s former nursing director Helen Moss admitted the drive for foundation status took priority over safe staffing.

In November, chair Robert Francis QC warned of a “tsunami” of patient anger heading towards the NHS. As the inquiry closed on 1 December after 139 days of public hearings, the NHS is battening down the hatches in preparation for the storm it will no doubt unleash in 2012.

The Hinchingbrooke franchise

Nearly a year after the landmark decision to franchise Hinchingbrooke Health Care Trust to private firm Circle, the Department of Health finally put pen to paper in November.

It is no real indication of where the private sector will make inroads into the NHS during the current parliament, which is too damaged on health to place another general hospital in private hands anytime soon. But what happens during the 10-year franchise will have a decisive influence on the future of the NHS’s relationship to the private sector.

As the chief executive of one of the UK’s major private providers mentioned, they all depend on Hinchingbrooke now. Any major failure at the hospital on Circle’s watch would likely rule out any further extension of private provision in secondary care for a long time. But if Circle fulfils its ambition to clear the hospital’s £40m debts without impacting on services, future governments will take a very different view of private sector care.

5 Readers' comments