Moorfields Eye Hospital responded to the huge task of delivering quality, safety and patient experience fit for the modern era by transforming its approach to clinical governance and clinical staff engagement. Bita Manzouri and colleagues explain how

Over the last 15 years the phrase “clinical governance” has permeated the consciousness of even the most die-hard medical traditionalists.

Definitions of it are effortlessly quoted in job applications or interviews for clinical posts in the NHS and the private sector. However, very few clinicians can with confidence and authority articulate what clinical governance involves on a practical level.

Most clinicians struggle translating concepts of clinical governance into practice. Clinical governance staff around the UK have found that one of the chief barriers to the delivery of meaningful clinical governance is the clinical staff themselves.

Put simply, clinical governance is an umbrella term used to describe activities which aim to maintain or improve the quality and safety of patient care. The quality agenda began in earnest with the Darzi report and now with revalidation and the new Health and Social Care Act a reality, quality and safety sit at the heart of the NHS.

All NHS staff and trusts must engage with this and demonstrate quality as central to their practice, if they are to continue to deliver healthcare.

Moorfields Eye Hospital Foundation Trust responded to the challenge of delivering quality, safety and patient experience fit for the modern era, by transforming its approach to clinical governance and clinical staff engagement over the last two years.

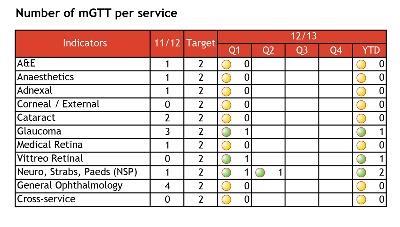

Commentary: modified global trigger tool (mGTT)

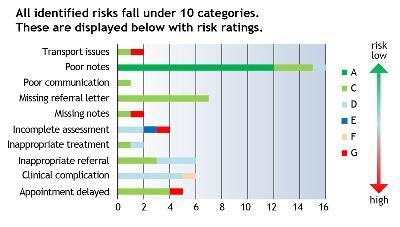

This audit identifies and categorises risk to patients by reviewing medical notes retrospectively and identifying any potential risks and adverse events graded according to IHI and Royal College of Ophthalmologists scales.

Recommendations are then made to improve patient safety before identified risks escalate to serious clinical incidents. Since 1 April 2012, four audit proposals have been approved by the clinical audit assessment committee.

For 2012/13 there are still eight services which have not registered the audit partly due to a lack of staffing resources, although posts are now starting to be filled.

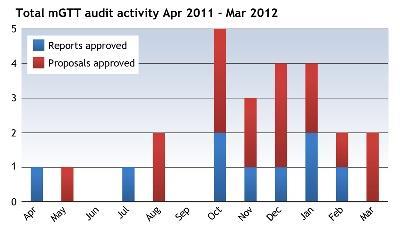

From April 2011 to March 2012, 16 mGTT audit proposals have been approved and nine completed reports have been received.

The audits have highlighted record-keeping issues and the importance of good clinical record keeping has been emphasised to clinical staff through presentations at the clinical governance half days and other training.

Each site and service aim to do two mGTTs per year.

There are several elements of clinical governance. Moorfields, like many other hospitals, has had many elements in place for a number of years.

These include clinical audit as a means of maintaining and improving standards of clinical practice, collection of incidents and maintenance of risk registers, complaints handling and resolution, and collation and feedback of patient experience data, each by dedicated teams. All aspects of trust activity are also governed by multiple protocols and clinical guidelines compliant with local and national policies.

‘Most audits were by trainees who moved through firms every four months and then on to other hospitals, meaning re-audits were frequently not completed’

Despite this, Moorfields lacked any truly strategic or systemic clinical governance plan until two years ago. For example, within clinical audit, there were no prioritised plans or annual reports of projects undertaken, and the audit department itself consisted of one member of staff.

Most audits were by trainees who moved through firms every four months and then on to other hospitals, meaning re-audits were frequently not completed. There was a paucity of clinical guidelines and protocols, with no standardisation on their format. Their location on the hospital intranet was varied and illogical, limiting their accessibility. Each individual governance area was working independently and was led by management with a notable lack of clinical involvement.

‘Darzi fellow’ pioneers

Changes began following the appointment of a new executive team, including a new medical director with a background in clinical governance. Following extensive consultation with stakeholders, Moorfields published a new 10-year strategy, Our Vision of Excellence, with a clear mission statement, in which patient-centred care and quality would be “the defining characteristic of all we do”.

A crucial first step was to ensure that the hospital had effective leadership and organisation of clinical governance. The committee structure was reorganised, with a new quality and safety committee reporting directly to the board, as well as revitalised and resourced clinical audit, clinical effectiveness and clinical governance committees with new terms of reference.

The hospital changed the operational structures to a system of clinical leadership, creating seven new clinical directors with operational responsibility for all medical, diagnostic and surgical services as well as satellite sites, reporting directly to the chief operating officer.

The trust appointed an additional clinical director responsible for quality and safety, reporting to the medical director. This structure required a corresponding programme of clinical leadership training and support.

Moorfields was one of the first hospitals to recruit clinical leadership ‘Darzi’ fellows, first starting in 2009. The Darzi fellows worked with a core group of trust consultants with a special interest in the area. They set up, with the help of learning and development staff, training programmes in clinical leadership and management, targeting particularly clinical and service directors, newly appointed consultants and trainee ophthalmologists.

The programmes combine a series of seminars covering major areas of skills, knowledge and participation in centrally registered developmental quality, innovation, productivity and prevention (QIPP) projects. It involves the fledgling clinical leaders leading a multidisciplinary group of managers, nurses, administrators, allied health professionals on a quality or service improvement project.

Major changes

Their learning is mentored by a consultant, and leadership competencies signed off against an adapted version of the Medical Leadership Competency Framework. Other development opportunities offered include paired learning with managers and opportunities to attend a number of high-level management meetings and committees, to ensure familiarity with the organisational and reporting structure of the trust.

The final structural change was to properly resource clinical governance with sufficient staff and infrastructure. In addition to the new clinical director for quality, the hospital has financed several new clinical audit posts, and partially merged the audit and revalidation teams.

This facilitates the production of the clinical outcome and quality information as well as the patient experience feedback required by current medical staff, and future clinical staff, for professional revalidation and accreditation.

As a consequence, there have been major changes in the way clinical quality, clinical safety, and the patient experience are monitored in the trust. A programme of three-monthly clinical governance half-day sessions has been established, of which three are service sub-specialty or site based, and the other an annual trust-wide meeting.

Each session has a standard agenda, including regular reviews and actioning for adverse events, audits, progress on action plans, and items directed by the quality team as issues arise.

For example, learning from serious incidents, safe consenting, as well as locally owned issues. There is now an agreed annual clinical audit plan, appropriately prioritised with clinical audits for each department and site as well as trustwide. The development of this annual clinical audit plan is supported by a bespoke electronic clinical audit management system, run by a dedicated audit IT staff member.

This allows registration, reporting and progress monitoring. It generates automatic e-mail communications and allows accurate monitoring of progress against plans. An annual clinical audit report is then published.

As part of the revised audit programme at Moorfields, there are regular reports on core clinical outcomes to provide a high level of quality assurance for the trust board, its patients and staff as well as commissioners.

Each department has agreed a limited number of key and widely accepted outcomes with standards based on available published evidence and Royal College recommendations to be achieved for frequent areas of practice. These will be assessed at least annually and quarterly once the new electronic patient record is fully functional in 2013/14.

Moorfields is actively obtaining the views of patients and stakeholders which include general practitioners, optometrists and commissioners, in deciding which further clinical outcomes to measure.

Silo working

As there is currently no national ophthalmic PROM (patient reported outcome measure), Moorfields is developing its own, using either amendments of existing validated tools or via research and development, creating new tools, to ensure that outcomes of care are measured from the perspective of the patient.

Moorfields is unusual in that it has over 20 sites spread across a wide geographical area. In an attempt to ensure consistency of practice as well as to proactively identify and address any problem areas, the hospital has developed a “modified global trigger tool audit”.

This examines basic levels of care and record keeping in outpatients. In addition, there is also a new programme of patient safety walk-arounds involving executive and non-executive directors. It is a two-stage process with initial visit and then a follow-up visit, being piloted at Bedford. Moorfields has also introduced new standardised templates and an approval system for all guidelines, protocols and policies as well as an improved intranet for easy access to such documents.

A key priority has been to move away from “silo” working. Integrated analysis of quality and safety reports from different departments and sites, as well as improvements in staffing and reporting structures, have helped to address this.

We have created a learning information group which draws together and analyses all adverse events such as incidents, complaints, claims and risks, making recommendations for action or escalation as appropriate. We also developed a combined performance, quality and risk dashboard for directorates to report performance data together with key measures under the headings of clinical effectiveness, patient safety, and patient experience. All essential parameters are reported on a single page with the latest data. These measures are designed to ensure that lessons learned in one area are rapidly disseminated across the trust.

The ambition of clinical governance and the quality agenda has been to completely transform the traditional culture and service delivery of NHS organisations to ensure better, safer, more patient-centred care. The achievement last year of NHS Litigation Authority level 3 status has been viewed by our staff as external recognition of our efforts. The challenge now is to demonstrate that this translates into real benefits for our patients.

Bita Manzouri is clinical leadership fellow, Declan Flanagan is consultant ophthalmologist, medical director, Melanie Hingorani is consultant ophthalmologist, clinical director for quality and safety at Moorfields Eye Hospital.

No comments yet