By establishing new ways to reach young people and improve transitions from adolescent to adult mental healthcare we can improve their wellbeing and society. Emma Stanton and colleagues explain

Rank the top five features of your mental health, substance misuse and sexual health services in order of importance

For most people, approaching your 18th birthday is a time of anticipation and excitement. But for young people in child and adolescent mental health services their coming of age can bring upheaval and uncertainty as they are referred into Adult Mental Health Services.

For various reasons, as elaborated below, transition from adolescent to adult services is often unsuccessful. A recent review conducted by Beacon UK demonstrated that only 3.2 per cent of child and adolescent mental health services’ patients in a London borough successfully transitioned to adult ones.

‘Many child and adolescent practitioners told us that they often found it difficult to identify appropriate services for their patients’

This is all the more concerning when one considers that right up into the twenties is a particularly important and highly sensitive developmental stage for a human brain. For the review, we considered two distinct questions:

- How can we improve transitions from child and adolescent to adult services for young people who are already using existing services?

- How can we reach young people who are not currently accessing services?

Organisation of existing services

Discussions with providers, commissioners and young people highlighted various drivers of the disconnect between child and adolescent health services and adult ones.

Many child and adolescent practitioners told us that they often found it difficult to identify appropriate services for their patients within adult services.

There are also differences in clinical orientation towards the individual. Children’s mental health services, as with paediatrics in general, tends to view the child in a more holistic manner, whereas adult services tend to be pathway based, organised around diagnoses.

‘Young people told us that they often felt uncomfortable and scared as an 18-year-old surrounded by older patients’

Subsequently, it is not always readily obvious where to refer an individual who has been supported for the last five years with a mental health problem. Often, equivalent services don’t exist. For example, ADHD services for adults are extremely rare, despite the fact that prevalence rates in young people have been increasing over the past 50 years. In our study, only 19 per cent of child and adolescent mental health services patients were referred on at all.

Find out more

Even when an appropriate adult service did exist, the clinical threshold for acceptance into the service tended to be significantly higher than in child ones. This meant that only 17 per cent of referrals were actually accepted. This may reflect service resource constraints.

However, potentially the most distressing problem with the current age limit of child services is the inappropriateness of many adult mental health services for someone who is legally an adult, but emotionally and psychologically very much less so. Young people told us that they often felt uncomfortable and scared as an 18 year old surrounded by older patients with sometimes disturbing mental health problems.

‘There is a significant proportion of young people with mental health problems who are not accessing services at all’

National guidelines exist on transitions best practices. While we recommend using the freely available benchmarking tool and implementing the guidelines, these do not necessarily address the core issues outlined above. Therefore, we propose that the upper age limit for child and adolescent mental health services be extended to, for example, 24. This does not mean that new referrals must be accepted into child services between 18 and 24, but that the service is granted greater flexibility to transition the young person to adult service at a time that best suits them.

Service innovation for unmet need

Comparison of child services’ and adult services’ activity, referrals and expected prevalence suggests that there is a significant proportion of young people with mental health problems who are not accessing services at all.

Studies have shown that an estimated 70-80 per cent of children with mental disorders go without care. Much of this may well be related to the stigma attached to a mental health diagnosis and even the act of asking for help.

‘The potential gains from intervening effectively in these young people’s mental health will be wide reaching and long lasting’

Closer examination of referrals suggests that there is a particular unmet need among young people from the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. Unfortunately, these young people’s circumstances put them at greater risk of mental health problems and it is not uncommon for them also to be known to the criminal justice system, which increases their risk of further mental health problems.

As a result of their circumstances, however, these young people tend to be the most resistant to engaging with statutory services of any kind.

A local London based charity, MAC UK has had particular success at engaging with gang members, typically the hardest to reach young people, through a pilot delivering one on one opportunistic psychological interventions.

This is undertaken in the course of working with gang members on projects of their choosing, such as setting up a record label. However, the pilot has been resource intensive and requires committed and skilled young clinicians who hang out on the streets where the gang members tend to be, until they strike up a relationship and gain agreement from an individual gang member to undertake a project.

The ideal service

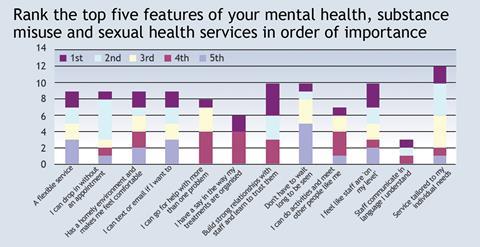

We separately surveyed young people about what they would like to see in mental health services specifically tailored to them and the results are shown in the graph below.

Combining what we heard from young people with learning from the pilot, we proposed the creation of a community based hub, offering something of interest to young people to get them in the door, such as a cafe with free internet, or a juice bar. The hub should not be branded as a statutory service, it should be in a readily accessible location and offer services relevant to young people in a way that they are comfortable with.

Also, child services can be combined with young people’s sexual health and substance misuse services. For maximum impact, collocating with benefits advice, housing and employment services, all tailored to young people, will provide a one stop shop in a minimally stigmatising setting, to lower the barriers to accessing services.

It is of paramount importance that we ask the young people what services they want to be able to access and what the offering should be that would be useful or attractive to them in the first place.

Young people have frequently said the main difficulty in finding a job is the absence of a CV demonstrating any prior work experience or references. If the community hub was to be set up incorporating some form of social enterprise then this could offer an opportunity to secure a first job and a reference, and this itself would strengthen the draw to get young people through the door. Of note, social enterprises such as this could also benefit from central government funding support.

Exemplar of best practice

In our specific case, when the local NHS commissioner took this proposal to the local authority board looking for a funding contribution, the local authority chief executive described the proposal as “an exemplar of best practice in how statutory services should be engaging with young people” and offered his wholehearted support. It makes sense for there to be pooled contributions from various services to the overall cost of setting up and running the hub.

The project will be on course to offer an innovative new service model with the potential to address the unmet mental health needs, sexual health and substance misuse problems of the local young people − as well as improving their opportunities to get employed.

Since the determinants of mental health are so broad and the impact of mental ill health so pervasive, the potential gains from intervening effectively in these young people’s mental health will be wide reaching and long lasting for the local population and society as a whole.

Dr Emma Stanton is chief executive, Dr David Cox is head of strategy, Dr Lizzie Tuckey is a senior analyst and Jess Szabo is a project manager at Beacon UK

No comments yet