It is preferable to manage the conflicts within CCGs than to attempt to eradicate them, argues Simon Cox

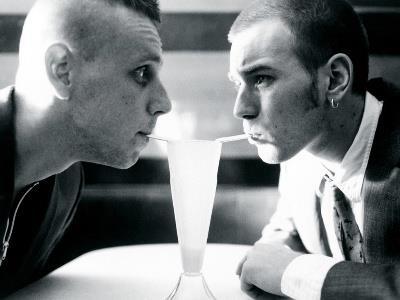

In a scene from the film Trainspotting, two characters, Spud and Renton, discuss how Spud should prepare for an imminent job interview. If he is seen to be obviously not interested in the job his social security is at risk; but if he is too good he may actually get the job. It is, in Renton’s words, a “tightrope”. Much like working in a clinical commissioning group (minus the drugs and milkshakes).

Tony Watson (2002) describes an inevitable, if possibly irreconcilable, tension within organisations. Organisations exist, in part, to impose control and create efficiency through managing diverse resources to achieve its ends.

But organisations must also accept a degree of autonomy from individuals working within them: indeed, in many cases promoting autonomy may improve performance.

Consequently, there will be a conflict between the desire for control, with the struggle for autonomy. This identifies the conflicts present within CCGs.

Choosing sides

‘Organisations that have a great deal of uniformity in their decision making may often make poor decisions’

On the one hand is the drive for innovation from clinical leaders working autonomously to provide improvements in care. On the other, a team of petty bureaucrats puts the clinical leaders in straitjackets so they are always and everywhere under control.

Another conflict is that on one side you have honest public servants striving to implement systems of good governance, against a sea of clinical mavericks with no regard for process, or even the law. On the other side are clinicians with a diverse range of conflicts of interest, flitting from priority to priority, only settling on what the latest fad or the one that best satisfies their self-interests.

The conflict I prefer is motivated clinicians with a real passion to improve patient care and who will not accept delays or obstructions due to “process”. On the other side are equally motivated managers seeking to support clinicians in improving care but within a “safe” environment, and while making the money fit. But the tensions will remain.

Desirable conflicts

These stresses may be managed through the establishment of a “negotiated order” in the organisation (Watson 2002; 2003), where the internal conflicts are not resolved, but managed as part of corporate life.

A requirement for CCGs may be to not rush into reducing the tensions: organisations that have a great deal of uniformity in their decision making may often make poor decisions (Irving Janis, 1982).

‘It is a tightrope, but all the better for it. Long may the tensions and the conflicts of the tightrope walker exist’

Therefore a degree of conflict in CCGs may not be just inevitable, but actually desirable. It is not accidental that the historical position of advocatus diaboli (devil’s advocate) in the Roman Catholic church was also called “promoter of the faith”. Only through a process of actively arguing against canonisation could the church be sure of its future saints.

A strategic objective for CCGs’ organisational development is to produce a negotiated order that promotes clinical innovation and leadership, while harnessing its energy to achieve objectives, within a governance framework that is safe, legal and financially balanced.

For both elements − innovative clinical leadership and sound corporate governance − they must provide appropriate assurance to themselves, the NHS Commissioning Board and the patients and public that they are making no decisions without. Yes, it is a tightrope, but all the better for it. Long may the tensions and the conflicts of the tightrope walker exist.

Simon Cox is accountable officer at NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG

2 Readers' comments