There is dwindling interest among commissioners in using ‘any qualified provider’ to increase competition and extend patient choice, an HSJ investigation has found.

Data gathered from 183 clinical commissioning groups under the Freedom of Information Act shows that a minority have opened new services up to any qualified provider in 2014-15, despite the government’s intention that the policy would be extended to an increasing range of services.

AQP was a key policy for extending patient choice and introducing competition between providers at the time CCGs were being established. It enables commissioners to set up “zero based” contracts, meaning providers have no guaranteed income but are paid based on how much activity they attract.

The Department of Health required every primary care trust to apply AQP to three service lines in 2012-13, with the intention of opening up more services to the policy via a “phased approach”.

However, our research found:

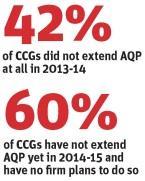

- of the 183 CCGs from which HSJ received information, 77 did not open any new services to any qualified provider in 2013-14;

- enthusiasm for the policy appears to waning as in 2014-15, 109 of the 183 had not extended any qualified provider and had no firm plans to do so; and

- AQP is only being used for marginal areas of spending. For the 39 CCGs that provided data on their 2013-14 expenditure on AQP, the median spend was £318,000. Only four of those commissioners spent more than £1m.

A DH spokeswoman told HSJ that the policy was unchanged, although there have been no further mandatory requirements for commissioners to extend AQP since 2012-13.

HSJ also found that most CCGs were using it only for the narrow range of services originally specified by the DH. Overwhelmingly the most popular services put out to AQP were audiology, non-obstetric ultrasound, podiatry, MRI, eye care, and back and neck pain services.

Of these, only eye care services, including ophthalmology and cataract surgery, were not covered by the original list of eight service areas the DH identified as priorities for implementing AQP in 2011.

However, a small number of CCGs have decided to adopt AQP more extensively. These include Nottingham City CCG, which is bringing in a wider range of providers for phlebotomy services and a “treatment room service” for minor injuries and wound treatment. The service would offer GPs an alternative referral route to local walk-in centres or acute emergency departments.

Great Yarmouth and Waveney CCG is using AQP to bring in new providers of neurological rehabilitation services.

Robert McGough, a partner at health specialist law firm Capsticks, said: “The hope was that bringing in AQP would create an easier route for commissioners, because you just allow patients to choose where they are treated without running a selection process.

“But it seems to have actually turned out to be much more intensive for commissioners. With AQP you can’t put a limit on the number of providers, so it then creates more contract management work, and it also becomes harder to manage the finances when you have so many new providers to pay.”

Steve Kell, co-chair of NHS Clinical Commissioners, said AQP was most useful to CCGs “where we are commissioning isolated services or areas such as diagnostics”.

“But increasingly we are commissioning for outcomes and joined up services, so AQP becomes less useful,” he added. “CCGs are focusing on key challenges like safety and the sustainability of NHS services, and not on simply increasing the number of providers for the sake of it.”

Bill Morgan, a partner at Incisive Health who was a special adviser to former health secretary Andrew Lansley, who proposed extending AQP, said: “If you want AQP to happen uniformly across the country it needs to be driven centrally. The biggest AQP policy in the last 10 years is free choice in elective care – that had to be driven centrally.

“If you didn’t do that it would be 20-25 years before it became widely used.”

9 Readers' comments