Identifying different groups within a population can reveal people’s needs more holistically. Shreshtha Trivedi explores a project in London that has done just that and the pros and cons of using such an approach

As the NHS faces tough demographic and financial challenges, it has been widely agreed that integrating health and social care can provide better care for patients with long term conditions and reduce dependencies on hospitals.

But how can we ensure seamless joined up care, which is efficient and that patients do not fall between the gaps?

‘Integrating health and social care can provider better care for patients with long term conditions’

The HSJ Summit last month hosted a fringe session “Population segmentation for integrated care”, sponsored by McKinsey.

Thomas Kibasi, and Sorcha McKenna, partner and principal at McKinsey, introduced the session by highlighting the benefits of segmentation. They said that it can be used in “understanding people’s wants and needs holistically” rather than according to the healthcare setting – acute, mental, community or social care.

- Roundtable: Putting patients at the centre of care

- Transform mental health with all-star leadership

- Visit the Hospital Transformation channel for more resources on integrated care

Make it matter

Traditionally, the health and social care sector has been organised around groups of professionals with similar skills rather than groups of people with similar needs. It has mostly been a one size fits all approach, not exactly focused on outcomes that matter to people.

For instance, most healthy adults need quick and convenient access to routine care and preventive services. However, this differs from the needs of people with long term physical conditions who might require more proactive care to prevent acute admissions.

‘Segmentation helps describe people’s needs in a meaningful way’

Similarly, people with severe and long term mental illness need regular access to specialised care.

Therefore, segmentation helps describe people’s needs in a meaningful way.

On the grid

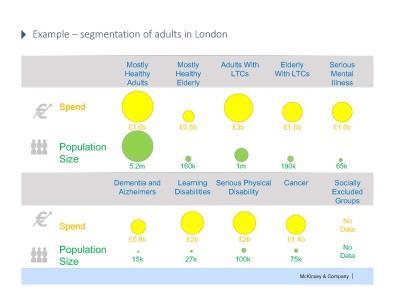

North West London Healthcare Trust, Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care, and the London Health Commission have identified 15 groups of population with broadly similar needs.

The grid (click on image, top right, or see McKinsey slideshow) was mostly welcomed by the delegates. One of the participants said she found it “great from a value perspective”. She, however, did question the need to include physical and mental long term conditions together and asked what they meant by “serious and enduring mental illness?”

Another delegate was of the opinion that the grid should have further subdivisions as the populations can be segmented even further.

Mr Kibasi said that the grid is a starting point. “It’s not saying you’re only under one group and getting only one sort of care,” he said.

He further added that some people have enduring mental health illness such as bipolar disorder. Mr Kibasi said: “Definitions can differ but the important question to ask is what is the care model? In this case it should be outbound.”

North West London collected integrated data sets across multiple settings health and social care, which was then analysed by McKinsey.

The speakers pointed out that more than just looking at how much is being spent where or whether the allocation of funds should be moved, the question of whether it was value for money should be addressed.

The pros and cons of capitation

They gave example of ChenMed in the US to illustrate their point.

A family run practice in Miami, ChenMed focuses on people with multiple long term conditions who are over the age of 65.

It has set up large primary care centres in the middle of communities - where people live. Some of its notable features include:

- providing transport from home for all patients;

- presence of multidisciplinary teams;

- long appointments and more than 85 per cent GP continuity – resulting in 35 per cent reduction in hospital admissions.

According to Mr Kibasi and Ms McKenna, ChenMed has been “disrupting the system”, with the capitation payment model being a big enabler in this. Unlike block contracts, the capitation model provides services on the basis of population groups.

“By aligning incentives through capitation we can get providers to work with commissioners in an effective way to achieve integrated care,” they said.

The duo came up with three characteristics of capitation:

- Predictable – As a component of the payments is paid up front, providers get the stability to plan and implement changes.

- Accountable – As a single provider or provider group accountable for the holistic needs of a person, there is less chance of them falling through the gaps between providers. For example, ChenMed is accountable for the care it provides to its patients

- Risk transfer – As providers take on greater risk, they have incentives to invest in preventative care and treat in the lowest cost settings. Risk transfer works as a force that asks providers to make changes.

Of course, capitation is not a panacea, having both advantages and disadvantages depending upon the system.

‘Capitation is a system worth adopting in certain integrated care ecosystems’

It can result in providers restricting access to certain services or attempting to “cherry pick” patients. It can also make providers abuse monopoly situations, such as reducing patient choice, or not investing in primary prevention if the contracts are too short.

However, it is definitely a system worth adopting in certain integrated care ecosystems.

The session concluded that besides segmentation and capitation, other major enablers of integrated care include empowering patients with informed choice and access to their records; allowing for accountability of delivery; aligning risk and rewards across the system; and making way for clinical decision making.

No comments yet