We should be building a culture of openness, not legislating one

The NHS needs more than statutory requirements to create transparency − it needs to welcome a cultural shift to openness and learning from mistakes, says Stephanie Bown

Government plans to place a statutory duty of candour on providers that fail to recognise the need for cultural change to achieve real openness when things go wrong.

‘Saying sorry is not enough. Patients want an explanation of what went wrong and why’

The long-ignored alarm bells of Mid Staffordhsire Foundation Trust finally have been heard with the recommendations for fundamental culture change set out in the Francis report.

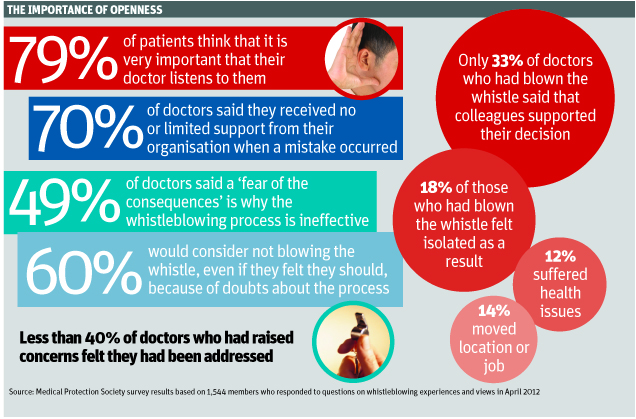

The report reveals the extent of the “blame and shame” culture that permeates some areas of the NHS: a culture that two-thirds of doctors surveyed by the Medical Protection Society say they believe will be difficult to overcome.

Health secretary Jeremy Hunt said in the government’s response to the Francis report that healthcare providers that conceal mistakes or failures that lead to harm of patients will be held to account under a new statutory duty of candour.

Added to the regulations in legislation governing the Care Quality Commission, the statutory duty would apply to all providers regulated by the CQC. A statutory duty of candour is not, as yet, being considered for individuals.

But the Medical Protection Society believes building a culture of openness, rather than legislating a contractual duty of openness, is what is needed. While you can mandate disclosure, legislation cannot deliver the attributes of high-quality and open communication such as empathy, sincerity and comprehensiveness that patients, as consumers of healthcare, expect from doctors today.

Rebuilding trust

When mistakes are made, patients want to know. Poor communication and staff attitudes are the top reasons for complaints in the NHS and seven out of 10 claims involve poor communication. Saying sorry is not enough. Patients want an explanation of what went wrong and why, and doctors need to rebuild the relationship of trust.

In our survey, 95 per cent of the public said that they think it is “fairly important” or “very important” that they receive an open and honest explanation of what went wrong, or an assurance that the problem that occurred is corrected. Doctors agree: 92 per cent believe they are always open and honest with patients, and 87 per cent of doctors recognise that in doing so they can help to reduce complaints.

‘A statutory duty may do more harm to the doctor-patient relationship, as patients feel doctors only share information because they have to’

Doctors already have a professional and ethical obligation, through the General Medical Council, to be open and honest when things go wrong. But 28 per cent of doctors find it difficult to communicate effectively with patients following adverse events.

Seventy per cent of doctors said they received no or limited support when a mistake occurred, with time constraints highlighted as a key factor in restricting their ability to communicate as effectively as they would wish. Healthcare organisations need to support their staff in fulfilling professional and ethical obligations to be open with patients when things go wrong by providing ongoing support, training, mentorship and ensuring senior clinicians lead by example.

We think improving managers’ and clinicians’ understanding of error as an inherent risk in medicine will lead to the type of environment where openness and learning from mistakes is the norm.

Creating a culture in healthcare whereby doctors are encouraged to understand and accept that errors can and do happen, and are taught how to handle them without fear of being branded incompetent, has to start with the undergraduate medical curriculum.

Many doctors already worry about the legal and professional consequences of making mistakes − and fear of legal sanction could be counterproductive, driving adverse event reporting underground. Changing a doctor’s reaction from one of fear into an eagerness to report, explain and learn from what went wrong can only happen through cultural change.

A culture of understanding

On a visit to the Hong Kong Hospital Authority last September I saw first-hand the culture of open disclosure that exists there. In 2007, the authority introduced an “open disclosure” policy where staff are actively encouraged to be open with patients when something goes wrong with their care. I came away thinking how they successfully managed to put the focus for staff on listening and learning, without fear of repercussions. That is exactly what we have to do here in the UK.

Openness is just the first part of a three-stage journey. The second stage is being open in reporting adverse events and near misses, so they can be explored and analysed. The third stage is a commitment to implement the learning, to prevent the same mistakes happening again.

We found 94 per cent of the public think it is important that those responsible learn lessons in order to prevent the same thing happening again, while nine in 10 say that it is important that they receive an apology. These figures support the many studies that show patients are motivated to take legal action primarily because they are angry, and their anger is often precipitated by no, incomplete or delayed information about what happened and why.

‘It is harder to change culture than change the law − but this is what the NHS, and patients, need’

The majority of patients say that the main reason they initiated litigation was “to make sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else”. Patients want information, and they want that information used to make healthcare safer. Legislation whereby patients and their families are only informed when there is a serious injury or death would fail to address the learning opportunities from near misses, which are free smoke alarms for patient safety.

Moreover, how feasible will it be for regulators to monitor behaviour under a regime of mandatory disclosure for serious adverse events both consistently and effectively? How will regulators enforce the prescribed sanctions for non-compliance with a disclosure?

We will be highlighting to the government that despite the understandable appeal of a legislated duty, this will not achieve the objective of high-quality open communication. The risk with any legislation is of creating a “tick-box” mentality, which does not support the intensely sensitive, personalised and patient-centred conversations that should happen with patients and their families when something has gone wrong. A statutory duty may do more harm to the doctor-patient relationship, as patients feel doctors only share information because they have to.

The meaningful, open disclosures that patients expect are more likely to be delivered by doctors committed to transparent working at all levels, rather than doctors forced to report adverse incidents through legislation and a top-down managerial approach.

It is harder to change culture than change the law − but this is what the NHS, and patients, need.

Dr Stephanie Bown is director of policy and communications at the Medical Protection Society