There is increasing evidence that understanding patients’ psychiatric conditions can help acute care providers improve physical health, say Noel Plumridge and Steven Reid.

On 29 October, Ed Miliband called for an end to the artificial divide between physical and mental health. It’s a divide reinforced by the organisation of NHS trusts.

Modern medicine is leading to increasing specialisation; an emphasis on technology and focus on shortened inpatient stays, meaning acute hospital staff often find it difficult to explore and address their patients’ psychological problems.

Yet untreated mental health problems in acute inpatients can result in delayed discharge, increased costs and increased mortality.

In February 2011, the Department of Health published No Health Without Mental Health - its strategy for mental health in England. One high-level objective, calling attention to the close interplay between physical and mental health, is to improve the mental well-being of people with physical ill health.

A&E’s key role

In acute hospitals, an estimated 28 per cent of inpatients have diagnosable psychiatric disorders. In older adults, where delirium and dementia are more prevalent, the proportion rises to 60 per cent.

Accident and emergency departments play an important role in managing acute mental health problems, with deliberate self-harm consistently listed as one of the top five causes of acute medical admission in the UK each year; 72 per cent of frequent attenders at A&E have a significant mental health problem.

So bridging the gap between physical and mental health care is essential; and in acute settings liaison psychiatry plays a vital role. Liaison psychiatry teams see A&E attenders, as well as people referred from inpatient wards and outpatient clinics. They respond to the needs of the acute hospital and must be flexible enough to manage a diverse range of mental health problems.

Problems referred to liaison psychiatry

- Psychological reactions to physical illness

- Deliberate self-harm

- Organic mental disorders, ie: delirium and dementia

- Alcohol and substance misuse

- Mental illness related to childbirth

- Behavioural disturbance

- Medically unexplained symptoms

Just how necessary liaison psychiatry has become is evident from recent experience in north west London. Provision in the sector had been patchy, with well resourced liaison psychiatry teams providing round the clock cover at the centrally located Chelsea and Westminster and St Mary’s hospitals. In contrast, three hospitals in the outer boroughs of Hillingdon, Northwick Park and Central Middlesex were reliant on visiting crisis teams.

‘Highly valued by patients and hospital staff alike, liaison psychiatry is integral to patient safety’

With acute trusts facing cost pressures, NHS North West London commissioned Central and North West London Foundation Trust, in partnership with West London Mental Health Trust, to develop a liaison psychiatry pilot project, supporting the achievement of waiting time targets, particularly the four-hour maximum wait in A&E.

The proposals also aligned with a mental health strategic priority of improving access to mental health care for patients in acute hospitals.

As well as improving patient experience and outcomes, it was expected that liaison psychiatry would have an effect on acute hospital productivity.

Strong evidence

This wasn’t altogether an act of faith. Evidence from a range of sources suggests liaison psychiatry reduces A&E reattendance by people with mental health problems and reduces readmissions and length of stay, particularly among older people where dementia frequently passes undetected and results in a prolonged admission.

In 2007, the National Audit Office reported that more than two-thirds of Lincolnshire acute hospital patients with dementia no longer needed to be there. They estimated these delayed discharges offered a potential annual cost saving of £6.5m.

More evidence followed with an economic evaluation of the influential Rapid Assessment Interface and Discharge team at City Hospital, Birmingham. RAID accrued cost savings of £3.5m in a year through early discharge and fewer readmissions. This represented a cost benefit ratio of four pounds saved for every one pound invested.

Central and North West London were set a tough timescale to be fully operational within three months. To measure performance they were also set three initial targets: people presenting at A&E were to be seen within one hour of referral; mental health-related breaches of the A&E four-hour target were to be cut; and all people aged 65 and over referred to liaison psychiatry were to have a medicines review.

The benefits of having liaison psychiatry clinicians based in A&E, as opposed to a visiting crisis team, were highlighted in the 2011 Mind report on crisis care, Listening to Experience.

Highly valued by patients and hospital staff alike, liaison psychiatry is also integral to patient safety. Prior to the launch of the pilot teams in north west London, both acute trusts had experienced serious incidents where people with mental health needs had left A&E without being seen.

Positive start

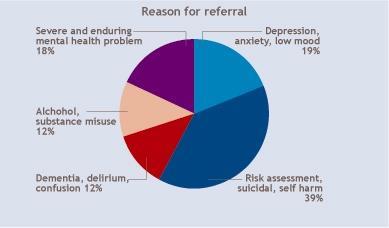

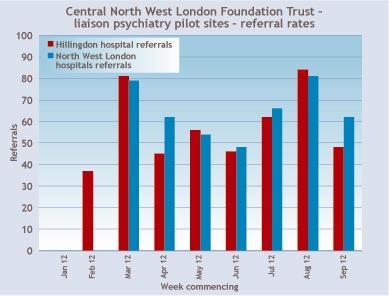

As anticipated, one team, embedded in the acute hospital with a single point of access and working collaboratively alongside acute trust staff, has led to a sharing of expertise that has increased the recognition of psychological distress in hospital patients. This is reflected in a consistently high referral rate (first graph) with a broad range of identified problems (second graph).

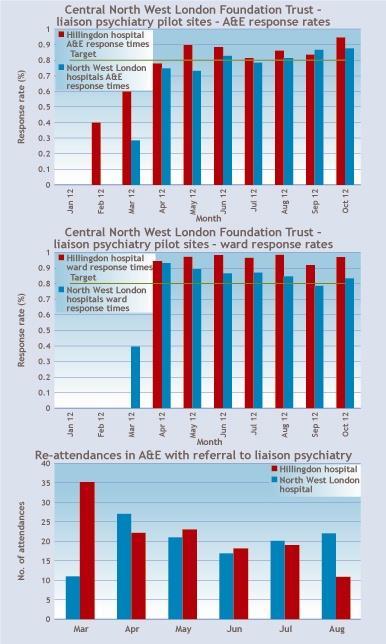

Early indicators from London have been positive. The target response time of one hour in A&E has been achieved at all sites (third graph), and the teams have reduced A&E waiting time breaches by 221 over the last six months.

‘We are delighted to have the support of the liaison psychiatry service. Our world is much better now they are here’

An interim analysis of the impact on acute length of stay, comparing admissions before and after the start of the project, suggests an average reduction of 1.3 days for patients with a mental health diagnosis. Evaluation is still in progress.

In Hillingdon A&E, reattendances are already showing a downward trend (graph four). In one example, a patient had attended Hillingdon Hospital A&E 21 times in the four months before an intervention by liaison psychiatry, following which she has presented just twice. The challenge is to isolate the effect of liaison psychiatry from other initiatives, but these findings are in line with the Birmingham RAID results.

The third outcome measure − requiring a review of medicines for older adults − reflects concerns about prescribing antipsychotic drugs to people with dementia. Improving the quality of dementia care has been highlighted as a strategic aim, particularly as the number of people with dementia is increasing and is expected to reach over 1 million in the next 10 years.

Shaping the future

Dementia is much more common in the acute hospital than in the community: 70 per cent of acute hospital beds are occupied by older people, and of those 30 per cent will typically have dementia, so identification is key.

Reducing antipsychotic prescriptions are a good marker of improving care. It’s estimated that two thirds of prescriptions are inappropriate. This is a cause for concern, given the potential side effects and the additional mortality risk due to stroke.

In addition to the success of new services in hitting their targets, they have been enthusiastically supported by acute hospital staff and managers. Professor Rory Shaw, medical director at the North West London Hospitals Trust, said: “We are all delighted to have the support of the liaison psychiatry service. Our world is much better now that you are here.”

‘The key now is to secure sustainable funding, allowing pilot projects to become an established service’

This view is supported by Maeve O’Callaghan-Harrington, deputy director of operations.

“The psychiatric liaison team is crucial to my role as head of site operations and I feel strongly that our patient journey has improved greatly through this enhanced service.”

A joint approach to managing the physical and mental aspects of patient care would seem a prime example of the oft-quoted need for better integration of services. What has also been impressive is the ability of Central and North West London to implement this service development so swiftly in a challenging financial environment.

The key now is to secure recurrent and sustainable funding, allowing this pilot project to become an established service.

At a time when North West London is embarking on shaping a healthier future, an ambitious programme aiming to improve community provision and centralise acute hospital care, liaison psychiatry services may be integral to the drive to reduce prolonged inpatient stays and avoidable admissions while improving quality of care.

Case studies

A 55 year old woman was admitted to a medical ward for investigation of severe weight loss. She had a history of ulcerative colitis but initial tests excluded this as a cause. Further tests were arranged to look for a hidden malignancy.

She was uncommunicative, thought to be due to her limited English. After three weeks she was continuing to lose weight and eating little. She persistently refused feeding by nasogastric tube so the gastroenterologists sought a psychiatric opinion.

The liaison psychiatry team found she was severely depressed. She refused food as she believed it was being poisoned by nursing staff.

Her rapidly deteriorating physical health necessitated emergency treatment, so she was given electroconvulsive therapy as an inpatient. After five days, her mental state improved markedly and she began to eat readily. After a further week of treatment she was discharged home.

A 79 year old man was admitted as an emergency following a heart attack. On the coronary care unit he became confused, aggressive and difficult to manage.

Liaison psychiatry found he lacked capacity to make decisions about his treatment. His confused state was managed with a behavioural approach and regular monitoring by psychiatric nurses.

A family member wanted to discharge the patient “against medical advice”, feeling he would be better managed at home. However, the cardiologists were clear he needed to remain in hospital.

As the patient lacked capacity, the liaison psychiatrist met the family and the medical team, exploring the cultural reasons behind the family’s wish for discharge. Working jointly they were able to prevent a precipitous early discharge, avoiding the high likelihood of an emergency readmission or a potentially fatal outcome.

Find out more

- No Health Without Mental Health: http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2011/07/mental-health-strategy/

- Faculty of Liaison Psychiatry: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/specialties/faculties/liaison.aspx

- Central and North West London Foundation Trust: http://www.cnwl.nhs.uk/

Noel Plumridge is an independent consultant and former NHS finance director. Steven Reid is a clinical director of psychological medicine at Central and North West London Foundation Trust.

Downloads

Raw data charts

Excel

No comments yet