A better understanding of risk will underpin the case for reducing today’s high bed occupancies.

The purpose of bed occupancy is to manage risk.

If the consequence of running out of beds is postponing some routine surgery, then that is a mild risk that you might tolerate a few times per month. But postponing cancer surgery or turning away women in labour are serious risks that you might only tolerate for a few hours per year or decade.

Such risk-based conversations are straightforwardly relevant to patient care. In contrast, bed occupancy conversations tend to be woolier and rest on generally-accepted (but weakly evidenced) numbers such as 85 per cent.

Yet there is an intimate relationship between the two. It must be possible to agree the acceptable risks and then, as a technical exercise, convert them into bed occupancies and therefore beds.

This is a problem that I (like many people) have been circling for decades, and to cut a long story short, the final pieces fell into place last year and I have now developed software that does exactly that.

The methods are described in detail here. And when I applied the software to hospitals in England and Scotland it became clear that the implications went a lot deeper.

Risk in a general hospital

Let’s illustrate using general and acute beds at a particular hospital.

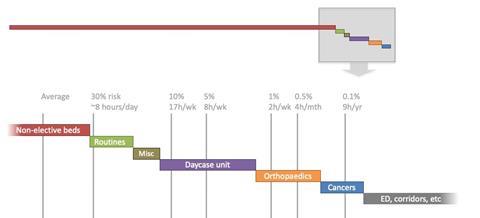

In the figure below, the long red bar at the top represents beds that are intended for non-elective patients. Then the shorter bars represent beds intended for elective patients, and this part has been expanded underneath.

The available beds are fixed, but the number of non-elective patients in them varies. So the software analyses the week-by-week and variation, and calculates the risks of non-elective patients requiring different numbers of beds. They are shown by the grey lines, with an indication of the frequency that each risk represents.

Clearly this hospital is under severe pressure. Routine inpatient surgery is postponed daily, the daycase unit is invaded weekly, and even cancer cancellations are not unknown.

It is a depressingly familiar scenario. But what can they do?

Achieving a safe bed occupancy

They could try increasing morning and weekend discharges, to reduce the daily and weekly variation in bed usage in the hope of reducing the risk of running out of beds. But here came the first surprise: it makes surprisingly little difference to risk.

Morning discharges do, however, shorten the typical duration of each bed crisis, which helps with four hour emergency department waits. But that is only true if bed occupancy is already very high, so morning discharges are a fire-fighting tactic rather than a strategic route to safer care.

A better approach is to reduce the longest lengths of stay and avoid admissions – both rightly emphasised by NHS England and NHS Improvement

A better approach is to reduce the longest lengths of stay and avoid admissions – both rightly emphasised by NHS England and NHS Improvement.

Idle time between patients is significant too, and comes from delays in communicating that the bed is empty and in cleaning and portering. The potential here is huge, and in many hospitals may be enough to reduce bed occupancy and risk to acceptable levels at moderate cost.

‘Hot’ and ‘cold’ sites

A more expensive option is to create more beds, and this needs a good business case that considers all the options. And here was the next surprise: it turns out that separating ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ facilities may not be such a good idea after all.

Moving elective care to a ‘cold’ site protects it from surges in non-elective demand. But there are consequences for the ‘hot’ site that only become clear when you can quantify the risks.

Moving elective care to a ‘cold’ site protects it from surges in non-elective demand. But there are consequences for the ‘hot’ site that only become clear when you can quantify the risks

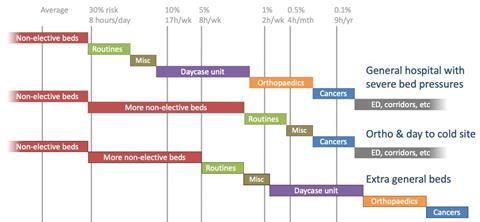

In the diagram below, the top line shows the status quo. Then in the first scenario, orthopaedics and day surgery move to new beds on a ‘cold’ site and their former beds are converted to non-elective use at the ‘hot’ site.

This reduces some risks, although the risk of postponing cancer patients remains uncomfortably high.

But the last option does better, at lower cost, simply by creating new beds at the ‘hot’ site. It also shows that beds could be released safely by moving only orthopaedics off-site.

This is just one example, but I suspect the same conclusion may apply fairly widely and explain why orthopaedics is the poster child for ’cold’ facilities.

The challenge

In today’s NHS it is uncontroversial to say that bed occupancies are too high, and cause longer emergency and elective waits, medical outliers and boarders, and clinical risks to patients.

Yet when asked what bed occupancy should be, the answer is usually a blanket assumption like 85 or 92 per cent, even though no single number could apply to every hospital. No wonder the National Audit Office said: “the NHS, including both NHS England and NHS Improvement, does not yet understand what the optimal level of beds is… for trusts to operate most efficiently.”

Instead we should start with a clinically-based conversation about acceptable risk, that builds the foundations for the firmest possible case for change. It is now a technical exercise to convert that risk, case by case, into bed occupancy.

And then the real work can focus on achieving it via length of stay reductions, admission avoidance, and – yes – the creation of extra staffed beds.

It won’t be cheap, and in some hospitals it may be costly. But until the acceptable risks are understood, the case for reducing today’s high bed occupancies will be hard to make.

1 Readers' comment