When GPs phone back patients who want to book an appointment, many often accept they do not need to visit the surgery or to go to A&E after all. Harry Longman explains the benefits this level of doctor access offers.

Why is demand for emergency care rising faster than demographic factors would predict, and what can we do about it? Annual rises of 6, 7 or 8 per cent suggest something is wrong with the system. The high variation of demand for emergency care between practices is more than can be explained by age of patients, deprivation or proximity to hospital.

Is perceived lack of rapid access to a GP a significant factor? In researching this issue I began asking those practices with the lowest accident and emergency attendance rates whether they could explain their results.

One GP gave an interesting answer: when patients call for an appointment he phones them back within a median of 26 minutes. Many of the patients do not need to come in, but those who do are offered a same day appointment.

This offered a plausible explanation for the low A&E attendance: patients have such confidence in access to their GP that they are less likely to attend hospital when they do not need to. This chimes with reports that 30-50 per cent of A&E attendees could have been dealt with in primary care. Could this be the simple, transferable innovation which turns around the rise in emergency demand?

At 77 per cent the Simpson Medical Practice in Manchester has the highest score in England for the patient experience survey question “very easy to speak to the doctor”.

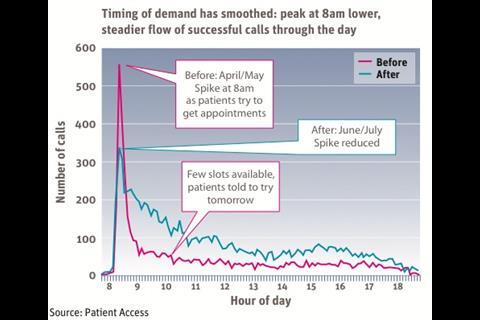

The receptionist, Sam, describes what happens when a patient calls, wanting the doctor. She identifies their medical record in the normal way, confirms their telephone number and asks for a brief description of the problem. She tells the patient that the doctor will call them back as soon as possible, most likely in less than an hour, unless they ask for a later call.

Her job is to put the patients in touch with the doctor, not to negotiate with them on how urgent their call is, or tell them there are no appointments left today, or to call back tomorrow. She is not fighting them off, but welcoming them.

Powerful evidence

The patient experience survey found the average practice scores just 9 per cent on “very easy to speak to the doctor”. I contacted the top 250, which all score above 27 per cent, and discovered that about 40 of them offer a service roughly equivalent to that at the Simpson Medical Practice. The key step is the telephone call from the doctor, as the first point of contact to all or most patient demand.

Talking to more and more of these practices: receptionists, practice managers and GPs, I saw a powerful body of evidence emerge about how the system works and its impact on patient experience, working lives and reducing A&E costs.

From the initial phone call, if either the doctor or the patient sees the need for a face to face appointment, the doctor asks the patient when they would like to come in. Around 80 per cent of patients say the same day, and the doctor arranges a time on the spot. Patients can ask for a later date if they wish.

In many cases – between 50 per cent and 80 per cent – no appointment is needed. The issue is dealt with by advice only, prescription or possibly a visit to the nurse. This generates the capacity to see the patients the doctor really needs to see as soon as possible, usually the same day.

Patients like the service, because it is fast and reliable, and they can always see a doctor on the day if they need to. Some practices report initial complaints from a few patients, unfamiliar at first with the new idea, but most of their concerns are allayed after finding how well it works.

The doctors like the system, because it gives them more control over their workload. They decide who comes to see them, and they are prepared when the patient arrives, having already spoken earlier.

During my research, doctors kept telling me that they were now going home on time, and some went even further to describe how this had brought them back from exhaustion and thoughts of leaving the profession.

Practice managers, who had often been initiators along with the GPs, found that this system enabled them to cope with the ups and downs, even the crises, with relative ease. They reported strong local reputations and growing list sizes. Practice nurses benefited too, from a growing level of appropriate referrals from the GPs.

The only complaint I heard frequently was that the primary care trust did not understand how the system could work without a set number of appointments available per day, and poor marks on 48-hour access targets because patients simply did not need to book 48 hours ahead, although they could if they wished.

I found practices operating this system all over the country. The same concept had been invented at least 18 times independently. Some introduced it 11 years ago, some within the last year. The numbers crept up as a few practices had learnt the system through local contacts. The practices were reporting similar outcomes in their own work, but were not aware of the subsequent reduced numbers attending A&E.

Cutting demand

By March 2011 I had found 29 practices using this system, and the key question was: what is the effect on A&E overall? Using NHS Comparators datasets for age/sex standardisation and deprivation indices the answer is that the 230,000 patients served by these practices are 27 per cent less likely than the mean to visit A&E.

Sir Muir Gray, chief knowledge officer for the NHS and Right Care workstream lead, invited me to bring the practices together for a conference held in June last year. By then 40 practices had been identified. Using better standardised data from the East Midlands Quality Observatory the increase in demand for A&E had been refined to 20 per cent – the same number held for the years 2009-10 and 2010-11.

Stories from practices all over the country have reinforced the benefits seen, the variety of contexts and the similarity, with small differences, of the method. The conference gave the mandate for a social enterprise to be formed to make the work available to all. The result is Patient Access, a community of more than 40 GP practices around England.

Case study: Liskeard

Oak Tree Surgery serves 11,000 patients in the Cornish market town of Liskeard. The staff recognised they had a problem: not enough time to meet the demands of their patients, and frustrated, overworked doctors.

Aware of research on patient access, they decided to change their model of work to one where the doctor initially telephones in response to a patient call. In making this change Oak Tree was supported by Falmouth GP Phil Dommett.

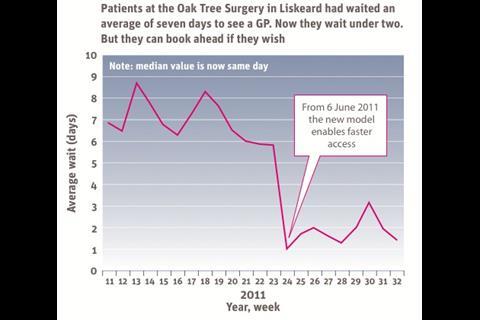

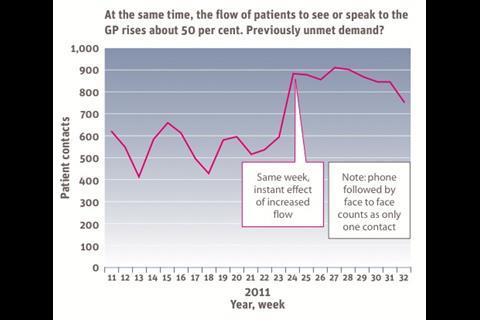

The new model began on 6 June 2011 and the results have been significant. The volume of patients dealt with in a week shot up by 50 per cent (see second graph, top of page), proving they had not been meeting demand. But far from being swamped, the practice was able to offer a superior service.

Waiting time to see a GP fell by 80 per cent (see first graph, top of page), from a seven day average. All patients who need to come in are offered same-day appointments, and most choose this although they can come another day if they wish. Did not attends also fell, as patients almost always turn up when the doctor says they want to see the patient.

The transformation is being achieved by abandoning the traditional one size fits all of a 10-minute appointment with the GP, arranged by reception, and the adoption of a different idea, where the patient’s problem comes first, and the GP helps to solve it in the best possible way.

Oak Tree GP Bianca Yu explains: “It’s hard work but more rewarding. We are not so frustrated as before, because we know we are seeing the right people, and giving a better service to patients.”

6 Readers' comments