Stephen Sutherland and Dr Ben Horner recommend eight steps to a bionic population health approach, building momentum to improve health and address inequalities

Sponsored by

Healthcare’s third great reform

Healthcare stands on the verge of its third great reform: from public health (clean water, infection control) in the late Victorian period; to disease treatment (institutionalised reactive care to patients) after the second world war; to population health (proactive care to support at-risk populations) in the third decade of the 21st Century.

Population health - addressing not only health and care services, but wider determinants of health, lifestyle and health behaviours - offers the potential for improved outcomes, with reduced overall cost. Why? Because clinical care accounts for only 20 per cent of explanatory factors for a population’s length and quality of life – significantly less than either social and economic factors, or health behaviours such as smoking.

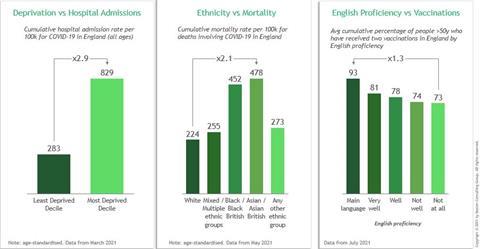

To date, population health efforts in England have shown positive signs of impact but there are no strong examples of population health being delivered sustainably at scale. However, covid has shone a light on the need to redouble efforts, highlighting health inequalities and showing that the NHS can move faster at covid speed. By building on Covid learnings and making disruptive changes at pace, ICSs have a real opportunity to make a step change in population health and genuinely tackle inequalities.

Exhibit 1: Covid outcome measures broken down by various drivers of inequality

How a bionic approach can unlock population health efforts

A core driver of the shift to the ICS model is to address the barriers around competition and payments that will allow population health to flourish. However, this will not be easy to do, particularly given the competing demands of new governance, an unprecedented activity backlog and expected financial tightening.

The pay-off for population health is potentially huge, but it will require investment – of time, money and leadership – to get to impact. Given this, the risk is that population health efforts will continue to flatter to deceive, set aside from the “core business” of partners within an ICS.

We argue that the investment is worth it – and that there are ways to tip the odds in favour of impact and sustainability. When we look internationally at health systems that have made sustained progress tackling inequalities through population health, there is a common theme: They are taking a bionic approach.

A bionic approach combines the strengths of human and technological capabilities to deliver lasting, sustainable change. It’s engaging with populations to support their own health – and using technology to make that easier. It’s energising clinicians and professionals to support population health – and giving them the tools to collaborate and share information to do so. It’s leaders who set ambitious targets for their population – and the data and analytical capability to target interventions for specific populations and track outcomes that matter.

Too often, population health approaches do not give sufficient weight to each of these elements.

Eight steps to a bionic approach

We recommend eight steps to a bionic population health approach, building momentum to improve health and address inequalities:

Strategy:

1. Put population health at the core. Develop a plan for population health that is owned by all ICS leaders (including providers) – not just the ICS population health team. Share in both the risk and reward. Ensure that those tasked with leading population health efforts have the right membership (including primary care and local authority), feel accountable for delivery, but also have the resources to get there.

2. Get going somewhere. Many pilots start with chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. These populations are often easier to identify and track outcomes. However, be aware of the need to look holistically at these populations’ needs - not just the primary condition – as well as the potential to gain momentum through quick win intervention. Kaiser Permanente, when developing population approaches, targeted breast screening alongside chronic diseases. Focussing on those populations waiting in the backlog for treatment so that they can be “waiting well” could be another early priority.

Technology

3. Use the available data. Bring together datasets to understand high impact opportunities and hidden communities. Data is starting to come together through Local Health and Care Records, but don’t neglect the right tools to help interrogate data for insight. It is not necessary to wait for a perfect dataset to get started: for example, Barts Health are using public health data to consider inequalities when prioritising their covid elective backlog.

4. Consider where digital tools can enhance care. Rather than applying digital point solutions, consider whole pathways, and how digital can enable. One Swedish provider has shifted to digital pre-operative assessment for Urology patients. A major Danish specialist hospital has invested in a slimline Holter monitor that can be posted to patients, links to their mobile, and offers real-time two-way communication. There are a plethora of Apps and remote monitoring technologies available - the question is less what to use, than how to apply it successfully so these tools are used.

Human

5. Activate communities and nudge healthy behaviours. Consider the best routes to engage with patients and communities. Consider social media – work on vaccine influencers has shown that the voices that impact a community may not be traditional community leaders. Join forces with social care and local community services. Population health is about changing behaviour in easy, simple ways: whether it is testing for diabetes during Ramadan to avoid the need for separate fasting in Qatar; or providing discounts on healthier food by using Apple Watches in Singapore - more than 150 governments and institutions globally are using nudges to impact behaviour. The NHS and local partners can do this too.

6. Hard-wire population health into clinicians and professionals’ ways of working. Create the right prompts in electronic health records; track interventions; and close the loop – give visibility on impact. In primary care in Switzerland, physicians are given key metrics around population health, which are tracked and shared weekly to help nudge positive behaviours.

Delivery

7. Test and scale – work rapidly to identify and execute “use cases” that deliver value quickly based on available resources. Aim for impact in 12 months (not three years). Track metrics from across the whole pathway to understand impact. Don’t get caught up in governance, process, or trying to find the “perfect” system; be prepared to refine and change course without fear of failure.

8. Create a bionic hub to drive scale and ongoing innovation. Scaling good practice doesn’t just happen. It needs dedicated skills and resource to scale effectively – even where the pilot is promising. Concentrating analytics capabilities, creating champions, upskilling staff, capturing outcomes, codifying knowledge, adapting learnings and celebrating success all require dedicated focus.

There is a clear opportunity to act on pandemic learnings to tackle health inequalities by helping providers set up a cross-system population health approach. However, it will only deliver the lasting, systematic change needed through a bionic approach. Balancing human and technology factors is key; people drive change but they need the tools to enable them to do so.

The authors would like to thank Cassandra Yong and Leonie Woodfinden.

No comments yet