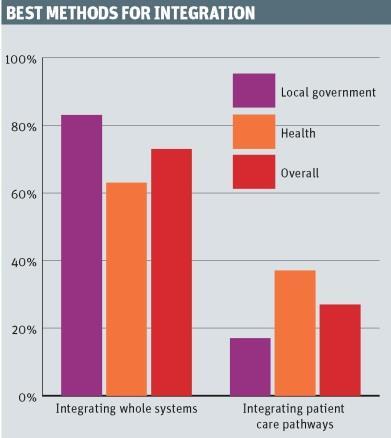

Local government and health leaders believe whole system integration models are a better option than pathways for specific conditions, our exclusive survey reveals. Rachel Dalton reports on the findings.

Decision makers across health and local government prefer whole system approaches to integration to those centred on pathways for specific conditions, exclusive research indicates.

HSJ and our sistle title Local Government Chronicle have undertaken a survey, in association with Bevan Brittan, of the chief executives and senior officers of councils, NHS providers and clinical commissioning groups.

It suggests that many people across councils and the NHS believe that attempts to integrate services around a particular condition, such as diabetes, create “vertical siloes” that prevent effective care.

Instead, leaders in both sectors revealed a preference for whole system integration models, in which all partners within a locality, including CCGs, local authorities, NHS providers - and potentially others such as housing and education - come together to provide a seamless service.

‘Historically there hasn’t been much engagement here between the NHS and local authorities, but I can’t see why not’

The results showed that overall, 73 per cent of respondents thought whole system integration was the best method, compared with 27 per cent who supported integrating patient care pathways.

Whole system integration was backed more strongly by local authorities than their health counterparts.

Some respondents were vocal in their criticism of the model.

Model critics

One local government respondent said: “[Care pathways are] neither personalised nor effective. The notion of single pathways reinforces the medical model of dealing with a part of someone’s body rather than with the person and their circumstances.”

Others said the model could be used but recommended ensuring services are patient centric to prevent siloes from developing.

One health respondent said: “Start by defining what ‘good’ looks like from the eyes of the patient and then work back, as opposed to the normal NHS tactic of [asking] ‘what does my organisation need to achieve to stay solvent this year?’”

Another stressed the need for all services involved to “sign up to a joint vision” and employ “effective planning and genuine partnership working”.

Although whole system integration was the preferred model, there were many reservations from both health and local government about the likelihood of it being achieved.

David Owens, partner in the commercial and infrastructure department at Bevan Brittan, warned that all encompassing systems could become “so big that it never happens”.

One health respondent said: “Whole system integration is unlikely without transformation change led by the Department of Health and availability of transitional funding.”

A local government participant said: “In practical terms, it is only realistic if health is brought into local authority control with an associated alignment of funding, allied to changes in constitutional responsibilities of elected members.”

Structures

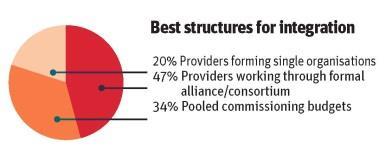

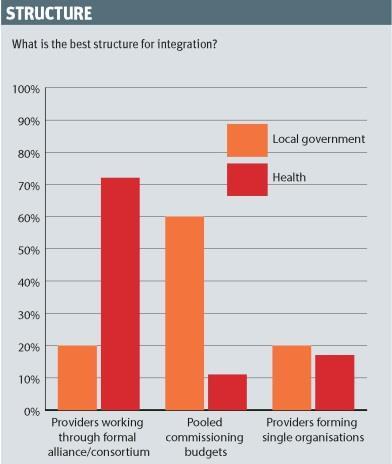

Despite their support for whole system integration, health and local government respondents revealed contrasting opinions on the ideal structure of integrated arrangements.

‘Personal budgets support isolation and not inclusion’

Among local government respondents, the most popular structure was pooled commissioning budgets (60 per cent), whereas health respondents showed little appetite for this method (11 per cent), instead opting for providers working through an alliance or consortium (71 per cent).

However, there was a similar lack of enthusiasm for separate providers coming together to form single organisations among local authority (19 per cent) and health (17 per cent) respondents.

Other services

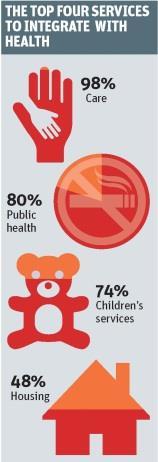

In keeping with the respondents’ preference for whole system change, participants indicated a variety of services to include in integration. Ninety-seven per cent said social care should be included; 80 per cent said public health; 47 per cent said children’s services; and 48 per cent said housing.

There were also several further suggestions for services from respondents including education and police and criminal justice, and some said support services such as human resources, finance and performance management could be integrated or shared between local authorities and the NHS.

Mr Owens said: “There is scope for back office collaboration. Historically, there hasn’t been much engagement here between the NHS and local authorities, but I can’t see why not, although if they use a shared service, they will need to consider the procurement issues.”

Personal budgets

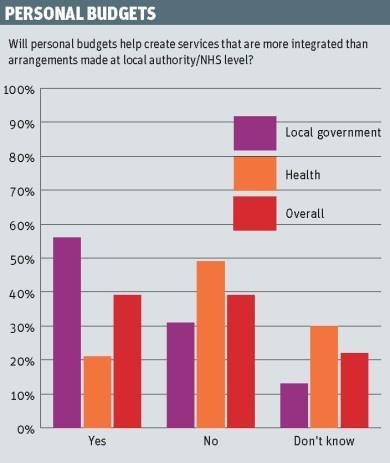

The jury is still out on the benefits of health and care personal budgets. Health chiefs remained unconvinced of their value whereas local authority respondents were far more enthusiastic.

‘There is uncertainty and anxiety in the NHS where they have much less experience of personal budgets and see them as a threat’

Just 21 per cent of health respondents felt personal budgets created more integrated services than arrangements made at local authority or NHS level, compared to 56 per cent of local government respondents.

A local authority respondent who felt personal budgets aided integration said: “Customers must decide where they can. We do not know best in many cases.”

Another added that personal budgets “would drive change if successful”.

Care fragmentation

However, an NHS respondent said: “Personal budgets support isolation and not inclusion.” While another added that they are “likely to fragment care with numerous different providers potentially inputting”.

Mr Owens said: “There is uncertainty and anxiety in the NHS where they have much less experience of personal budgets and see them as a threat. Personal budgets may mean there are changes in the way services are delivered but [the NHS] is being too focused on current provision.”

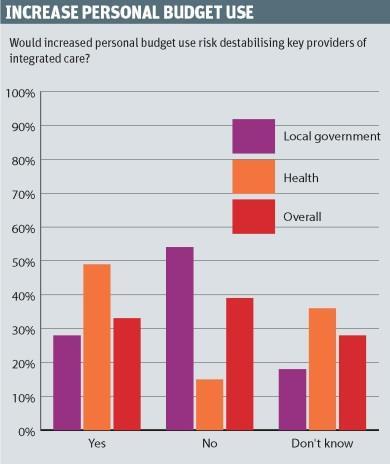

When asked whether an increased use of personal budgets would risk destabilising integrated care providers, 49 per cent of health service respondents answered “yes” compared with 28 per cent of the local authority group.

However, some respondents were sanguine about the risk to these providers. On the local government side, one said: “That is a risk we have to face.”

Another added: “That’s not necessarily a bad thing.”

A health service respondent said that the destabilisation of providers would “focus the strategy and operational plan”.

Culture

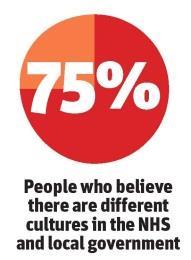

Most local authority and health chief executives thought there were different cultures between their two sectors.

‘The fear of failure has made us risk averse in how we apply the rules’

Respondents gave several suggestions for preparing frontline staff to work in an integrated system.

“Emphasise the shared long term goal and the culture challenges and how they can be addressed,” said one respondent.

“Examine the skill mix and plan with Health Education England for an appropriate workforce,” another participant said. Another advocated “integrated organisational development and training plans” and “single qualifications where appropriate”.

Legal barriers

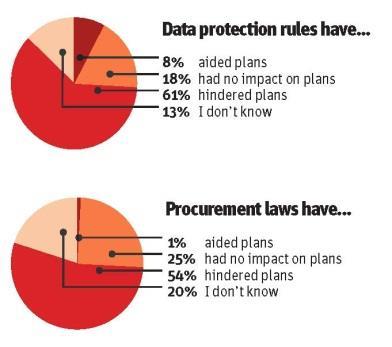

The survey asked whether data protection, procurement and competition rules have blocked integration plans.

Sixty-one per cent of respondents said that data protection rules had hindered their integration plans, compared to 19 per cent who said these rules had not had any impact.

Respondents’ reactions reflected this: “The fear of failure has made us risk averse in how we apply the rules.”

“Getting explicit consent to share info across health and social care is time consuming and fraught with difficulties,” another said.

One complained that “the legislation is significantly unhelpful”.

Competition laws

The confusion over rules extended to procurement and competition laws. Fifty-four per cent of respondents said procurement and competition laws have held up integration plans.

‘We have to dance around handbags to ensure that there are no competition problems’

“There is a great deal of uncertainty around NHS contracts and whether they must be retendered,” said one.

“My organisation wants to integrate and we have to dance around handbags to ensure that there are no competition problems,” another added.

Others railed against the rules themselves: “To the public, competition is a ridiculous notion. They just want quality local services.

“Forcing expensive procurement is poor use of public money.”

Mr Owens said that the rules - the NHS Patient and Procurement Choice Regulations 2013 and the Health and Social Care Act 2012 - were vague.

“The guidance on these says there is no default that you must tender, but the information on how and what to do when you just award a contract is a bit unclear,” he said.

Better care fund: the future?

When asked what impact the better care fund has had on their integration plans for 2015-16, several respondents said it had been small or non-existent.

“There has been an increased number of non-recurrent funded pilot schemes,” one respondent said.

Another added they had “a detailed plan” but that “action was less in evidence”.

Some even said that the better care fund has “slowed integration down locally”

However, a few were more positive. One said the better care fund had resulted in “more attention (correctly) focused on working out what will keep people out

of hospital” with a greater focus on prevention and reablement.

- This survey was carried out in May and attracted 117 responses, 44 of which came from people working in local authorities and 73 from those working in the NHS.

David Owens on useful data

The survey has produced some interesting results, although in many respects it confirms the view that integration is at different stages in different places, and for many there is still much scope to truly take things forward.

Key areas where there are perceived legal obstacles to progress are in relation to procurements, competition law and data protection. While these areas can create problems, there are options that enable organisations to move ahead without taking undue risk if there is the service justification and the leadership locally to push a proposal forward.

The starting point should always be: “How can we improve services for the user?”

There are wide variations between outcomes and investment in different areas and where there is a lack of correlation between these indicators this may indicate an area for review. Any proposal needs to demonstrate how it will drive better outcomes for the population and provide appropriate levels of evidence around this.

It is also important to get both professional support and service user engagement in place early, to ensure there is a groundswell of support to carry the proposal past any potential organisational opposition, as well as any possible public reaction against changes.

At the early stages of this, it will be sensible to plan for any service delivery changes and whether these may require alterations to existing contracts or the commissioning of new services. Options here include seeking to change service delivery and building in amplified obligations to cooperate, without requiring tendering.

Early planning can also minimise the risks of data transfer being a problem by ensuring that the appropriate protocols are in place. Once again, an emphasis on improving outcomes for service users is often a critical part of the process.

Given the apparent pre-election commitment from Jeremy Hunt that more money will flow through the better care fund, it is safe to assume that the fund will continue and potentially grow.

It is also clear from the adoption of Manchester as the model for devolution that extensive co-commissioning of health and social care services will be expected in any local devolution deal.

Now is a good time to consider how schemes can be developed so they can act as an engine for joint working and the delivery of integrated services. However, this will also raise challenging questions about how to manage the governance aspects with local health and wellbeing boards.

David Owens, partner, commercial and infrastructure, Bevan Brittan

No comments yet