Technology-enabled virtual wards can be an important component of successfully and sustainably addressing the discharge to assess challenge

The NHS continues to face unprecedented challenges. As well as the longest ambulance response and accident and emergency wait times on record, the number of clinically-viable patients waiting to be discharged exceeded 14,000 per day for the first time in January (refer to fig 1).

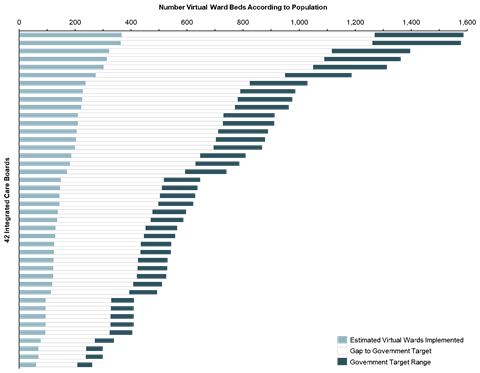

It is widely recognised that fixing the issues at the “back door” are crucial to addressing the problems throughout the care pathway. Virtual wards have been identified as one of a number of measures to deliver a step change improvement in discharge to assess performance across NHS England, with 40 - 50 virtual ward beds being recommended per 100,000 population. To meet this aspiration, integrated care boards and trusts will need to implement, establish and operate between 25,000 and 31,000 virtual beds nationally to ensure that NHS bed capacity is reserved for those patients who truly need it.

Sponsored by

Akeso’s research shows that positive progress has been made over the winter months, with approximately 7,000 (or 25 per cent) virtual beds now in place, but this leaves a huge gap to be closed over the summer. The challenge is compounded by the need to positively influence clinician and patient perception and receptivity to promoting and accepting virtual care, so that utilisation can be lifted from 55 per cent at the same time.

For the past nine months, Akeso has worked with Masimo International, a leading provider of in-patient and remote patient monitoring technology who has implemented several technology-led virtual wards with providers in NHSE and Wales, to fully understand the opportunity for technology-led virtual wards. Our experience suggests that many of the challenges can be addressed by breaking up the virtual ward implementation task into three phases: planning, implementation, and adoption.

Planning: adding local context to national targets

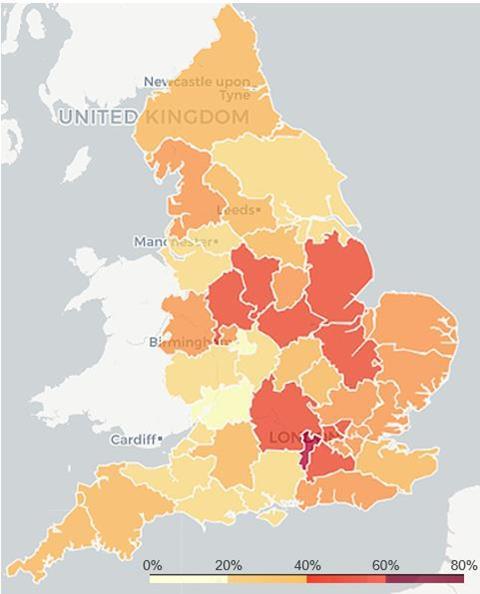

Whilst guidance on virtual ward capacity required and possible operating models has been issued nationally, in our experience, what this means at an ICB and trust level, both volumetrically, clinically and operationally is very much left open to interpretation. Our ICB population-led model (see fig 2) and engagement with NHS provider leaders across the country, indicates that there is a significant gap to be closed over the summer which has yet to be fully recognised and appreciated.

The need to interpret and translate these absolute numbers by provider and prioritise care pathways will necessitate the active leadership, involvement, and support of care providers, both NHS and private, within each and every ICB up and down the primary, acute, and tertiary care spectrum.

Implementation: leveraging integrated partnerships

Traditional virtual ward models which seek to use telehealth services and increased use of routine home visits further exposes the systemic workforce issues in the NHS. In our experience, technology-enabled virtual wards when implemented correctly, can provide “as near to” hospital grade monitoring of the patient in their own home supported with automated, care pathway-specific, secure clinical decision support to help prioritise clinical interventions, relieving pressure on healthcare workforce, rather than adding to it. Furthermore, a coordinated ICB-led approach to delivering these interventions, enables a scalable place-based strategy, which ensures standards and equity of care for all patients. Early results from pilot implementations have been promising, yielding a 36 per cent reduction in average length of stay and 38 per cent reduction in readmission.

Adoption: recognising the importance of patient education

Whilst on trend, the use of the word “virtual” can lead to a misconception among clinicians and patients, that a reduced standard of care is being provided. The right workforce training combined with patient education is key to overcoming misinterpretation and gaining adoption. It is important to communicate to patients upon admission that transfer into a virtual ward is not necessarily a discharge and that they will remain under consultant-led care in many cases. Patient education from the outset to manage expectations should be built into the operating model, with a recent study demonstrating 83 per cent patients agreeing their recovery was improved by going home earlier via virtual wards.

Despite the progress to date, with more than two-thirds of the virtual ward beds left to implement by the end of the year, the time to take advantage of this opportunity is now. Our experience reassures us that with thorough planning to navigate complex provider landscape and pathways, partnerships within ICBs to support workforce constraints and improvements in patient confidence, technology-enabled virtual wards can be a key part of addressing the discharge to assess challenge successfully and sustainably.

If you would like to learn more about our insights on adopting and scaling technology-led virtual wards, please click here. Also watch out for our HSJ roundtable to be released in April, where we’ll be discussing the barriers and solutions to scaling up virtual wards with leading experts in this space.