The NHS Atlas of Variation in Diagnostic Services has implications across the healthcare system for achieving better value and improving services, write Erika Denton and colleagues

The atlas is the first to cover the role of diagnosis, providing 69 maps of diagnostics use across England, including for imaging

The NHS Atlas of Variation in Diagnostic Services is the latest in the atlas series produced by NHS Right Care, looking at variation in specific areas of healthcare. The atlas is the first to cover the role of diagnosis, providing 69 maps of diagnostics use across England, including imaging, endoscopy, physiological diagnostics, pathology and genetics. Also for the first time, some data is available at clinical commissioning group level.

Understanding variation

The atlas integrates three different kinds of knowledge: statistics, research and experience (in the form of case studies). Confirmation of variation in diagnostic services is not in itself a surprise. However, its extent does provide food for thought, particularly when considered in relation to high mortality diseases and prevalent long term conditions.

Variation in NHS diagnostic services nation-wide

| Atlas map number | Diagnostic service | Level of national variation* |

| Cardio vascular disease | ||

| 6 | Time from hospital arrival to brain imaging for stroke | 26-fold |

| 28 | Echocardiography | Four-fold |

| 49 | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLC) tests | Six-fold |

| Respiratory disease | ||

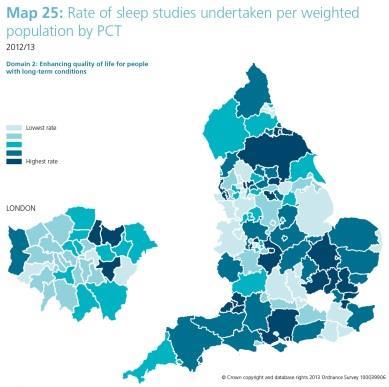

| 25 | Sleep studies | 23-fold |

| Cancer | ||

| 4 | PET-CT scan from independent centres | 14-fold |

| 36 | Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests | five-fold |

| 69 | Genetic breast cancer tests | Six-fold (area teams) |

| Diabetes | ||

| 42 | Blood glucose (fasting) tests for diabetes | More than 1,000-fold |

| 43 | Glucose (2-hours post) tests | 184-fold |

* Levels adjusted by excluding the highest and lowest rate PCTs/trusts.

These levels of variation confirm the significant opportunities that exist to improve both effectiveness (benefiting the patient) and efficiency (benefiting the healthcare system). In fact, the role of this and other atlases is to encourage questions. Where is there variation? Why does it occur? Does it matter? How do we compare? What is the benchmark to be applied?

The atlas shows that some very important tests are not as widely available as they should be, and therefore patients are not getting referred for some tests in some parts of the country. At the other end of the scale, certain tests may be overused because of a lack of understanding about what is appropriate. There are already useful tools to address these situations, such as the iRefer referral guidance produced by the Royal College of Radiologists.

‘The atlas shows that some very important tests are not as widely available as they should be, while certain tests may be overused’

The most obvious cause of variation is not unique to diagnostics. Access to many NHS services reflects a pattern of historical provision. Services tend to develop locally and generically through the expertise, interest and enthusiasm of people on the ground. This may partly explain the sporadic provision, for example, of sleep studies (even when they are recognised as increasingly important in understanding issues associated with obesity) or uterine artery embolisation, a treatment approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for symptomatic uterine fibroids.

Triangulating atlas maps with other data can help to identify whether the variation is rooted in clinical practice or awareness. In particular, looking at patterns of diagnostics use and the human impact of disease outcomes makes the data more meaningful (for instance, studying cervical screening rates alongside cancer deaths and the use of other tests).

Care must be taken not to over-conclude from the atlas, but used properly and with other information sources it can begin to suggest a pattern of behaviour and use that can be used to improve services for patients.

Embracing the implications

The NHS Atlas of Variation in Diagnostic Services has implications across the healthcare system.

For the public

Understanding the risks and limitations of modern diagnostic technology is just as important as knowing the benefits. Good guidance for patients is needed on how to present and describe symptoms clearly for clinicians. It is essential that this information is made available at the right time before and after face to face consultations, as well as through digital platforms such as Lab Tests Online and the Royal College of Radiologists website.

For clinicians

The management of symptoms is one of the most challenging aspects of clinical practice. Specialists need to investigate variations in practice within the wider population for which they are responsible, as well as providing high quality care for the proportion referred to them. In this regard, evidence based referral guidelines have a valuable role to play.

For commissioners

Diagnostics has been a difficult area for commissioners, because relevant data about costs and activity has often been buried deep within hospital block contracts, budgets and information systems. An additional complication has been the development of near-patient testing in health centres at apparently low cost, outside hospital contracts.

There are two possible ways forward:

- Programme based commissioning, such as the contract for musculoskeletal conditions led by Oldham CCG. This enables diagnostic services to be included within the overall scope, while resources such as the Health Foundation’s STAR tool can show the relative value of investment in prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

- Commissioning imaging, pathology or other diagnostic activity in a holistic manner, as a discreet service supporting the full range of healthcare.

For diagnostics professionals

Those providing diagnostic services, such as clinical biochemists, radiologists and pathologists, do much excellent work. However, historically it has not been routine in all areas to challenge the value of interventions requested by clinicians. In radiology, it is thought that some unwarranted variation may relate to a lack of confidence in clinical decision making, and the use of imaging to exclude rather than to confirm diagnoses.

It is clear that the specialties involved in diagnostics can add value; not only by providing high quality services for patients who have been referred for testing, but also by developing:

- Population based systems of care, where the focus is on the entire system rather than individual episodes.

- A knowledge service for individual patients using the test report to provide not only data to the referring clinician, but also information, options and support to the patient themselves.

For NHS trusts

Diagnostics support the entire range of services offered by trusts and are also in considerable demand from general practice. A very high level of quality is being achieved. In fact, it could be argued that there are few aspects of the health service more committed to safety and the principles of external quality assurance than laboratory and imaging services.

Despite this, each NHS trust needs to recognise the value of their staff and realise the potential for developing diagnostics as knowledge services, not simply as technology services.

There may be financial disincentives to revising the current model, where the productivity of diagnostics professionals is primarily judged by direct service delivery. However, the business model would change if commissioners were to specify that they wish to pay for the time of pathologists, scientists and radiologists to be used in providing knowledge, rather than simply providing assays, reports and interventions.

For research

The National Institute of Health Research has already increased the level of priority attached to research into diagnostic services and diagnoses. The institute will continue to be engaged in this debate.

Looking ahead

A workshop was held at the launch of the NHS Atlas of Variation in Diagnostic Services, bringing together royal colleges and professional associations, commissioners and delegates from industry. Delegates agreed that the management of symptoms and the process of diagnosis is one of the most challenging aspects of healthcare. Nevertheless, it was thought that much could be done to:

- improve the accuracy of diagnosis;

- increase the value derived from the skills and technology within diagnostics; and

- reduce harm resulting from over-diagnosis.

This principle of collaboration will continue. It will help to maximise the opportunities presented by the collection of data that enables variation to be examined to a level of detail never possible before.

The aim is to establish a population based approach. With diagnostics in particular, a focus on the prevention agenda as well as treatment will help the NHS to meet its financial challenges.

At the same time, there is a clear opportunity to work towards establishing optimum intervention and referral rates. Patient groups can also be involved and encouraged to ask questions about variations in clinical behaviour and service provision.

Therefore by taking ownership and addressing the variation highlighted by the atlas, commissioners, clinicians and other professionals will improve quality, increase equity and make better use of their resources. In other words, they will achieve better value healthcare.

Professor Erika Denton is national clinical director for diagnostics, Professor Sue Hill is chief scientific officer and Professor Jo Martin is national clinical director for pathology at NHS England; Sir Muir Gray is director at NHS Right Care; and Dr Giles Maskell is president of the Royal College of Radiologists

No comments yet