Making the health service sustainable will have an impact on the environment and public health, but a big part of its appeal is the savings it can drive, says Noel Plumridge

Four years after the launch of the NHS carbon reduction strategy for England − a pioneering initiative in its day − two new publications reveal a deepening awareness of climate change’s broader and profound impact on health strategy, and also that more sustainable ways of working may actually hold the key to quality, innovation, productivity and prevention savings.

‘The NHS compliance strategy requires a 10 per cent reduction in emissions by 2015. These targets are as daunting as a ski-jump’

NHS Midlands and East’s sustainability and transition management plan, launched in February at a conference in Leicester, examines the scope of sustainability in the health sector and how it might be achieved within changing NHS structures. Meanwhile, the NHS Sustainable Development Unit has launched a national consultation on what might constitute a sustainable development strategy for the entire health, public health and social care system.

Both take the scope of sustainability well beyond carbon reduction. And, interestingly for NHS managers, they reinforce widely held views about what might be affordable in the 21st century’s tighter economic circumstances.

Great aspirations

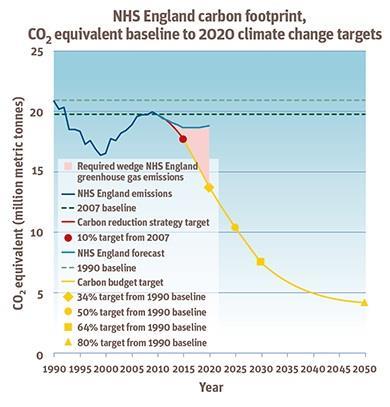

This is not to diminish the importance of carbon reduction. Moreover, whereas many sustainability plans are couched in the language of “ambitions”, when dealing with carbon reduction the NHS has clear aspirations. The Climate Change Act imposes a target of a 34 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2020, and more severe targets in the longer term. The NHS compliance strategy requires a 10 per cent reduction in emissions by 2015. Presented in graphical form, these targets are as daunting as a ski-jump:

Daunting perhaps, but progress has been impressive. During the last five years, NHS building energy use has fallen by 1.9 per cent, despite unusually cold winters and an 11.4 per cent increase in measured activity. Last year saw a 1.4 per cent drop in NHS water use.

Local initiatives have been at the heart of these achievements. The Leicester conference heard about Sandwell and West Birmingham Hospitals Trust’s carbon management plan, which is pursuing a 15 per cent reduction in carbon use through techniques ranging from boiler replacement to computer shutdown software.

Managing the impact of transport also features prominently. Norfolk Community Health and Care Trust − as a community provider heavily reliant on car mileage − managed to trim carbon emissions in this area by a third between 2007 and 2010.

East of England Ambulance Service, another extensive user of motor vehicles, has introduced working methods designed around telephone triage by clinical specialists, aimed at providing the most appropriate response to calls.

Case study: Norfolk Community Health and Care Trust

In 2012 the Public Sector Sustainability Association named the trust “most sustainable NHS organisation”.

Paul Cracknell, director of strategy and transformation at the trust, explains: “We have made great progress in reducing our carbon emissions. Our ongoing cost improvement programmes aim to increase use of cheaper, carbon-capped alternatives such as lease and pool cars to continue the success we have had in reducing our fleet emissions.

“As a rural community provider much of our carbon footprint is generated by an ageing estate and multiple sites. Our approach to sustainability is increasingly focused on adding social value to the communities of which we are a part through how we use our assets and deploy our people and systems.”

Case study: East of England Ambulance Service Trust

The trust, which serves a huge and largely rural area, has found real benefits in different approaches to ambulance response.

Lauren Smith, head of financial development at the trust, says: “Advanced triage of non-life-threatening calls provides alternative treatment pathways, often enabling patients to remain out of hospital. This reduces pressure on the hospital system, focuses ambulance transport on life-threatening calls and reduces vehicles’ carbon emissions. It supports a sustainable healthcare system, while also giving patients what they want.

“Our cycle response units,” Ms Smith adds, “are a huge success story. They are carbon-free and have a fantastic response rate, and the staff are keeping fit while at work.”

Such reductions in carbon use are already making a tangible contribution to QIPP savings. Reduced building energy usage, according to the Sustainable Development Unit, has provided direct energy savings of around £10m. With energy, fuel and other resource costs rising steadily, achieving target levels of future reduction offers a credible route to ever-more impressive cash savings. Energy efficiency is an integral part of overall NHS efficiency.

The health impact of climate change

But it’s not just about energy efficiency. At the Leicester conference Dr Felicity Harvey, director general for public health at the Department of Health, described some of the anticipated health consequences of climate change.

These range from increases in cardiovascular and respiratory illness, resulting from changing seasonal patterns and pollen levels; to increased levels of sunburn, skin cancers and cataracts arising from higher levels of ultraviolet radiation; and increased incidence of food-, water- and insect-borne diseases. There are also significant mental health consequences, already being identified in connection with recent flooding in parts of England.

‘The quest for adaptation at the same time as dramatic carbon reduction calls for a different model of delivering healthcare’

Remember the European health crisis prompted by the heat wave of 2003? By 2040, warns Dr Harvey, those extremes are likely to be our normal summer temperatures. And that assumes ambitious target levels of carbon reduction required under the Climate Change Act are actually achieved.

Then there are the indirect effects on the health system of climate change elsewhere on the planet. Among those being forecast are disruption to food and water supplies, influxes of climate change refugees (alongside more local shifts of population) and growing unreliability of transport infrastructure.

Taken together, these suggest the environment in which healthcare will be delivered in future decades is likely to be radically different. From the current focus on “resilience” – increased flood risk, for instance, makes it a good idea not to locate one’s IT hub in the hospital basement – the sustainable development unit is also urging a shift to “adaptation”: actively responding to the projected and current impacts of climate change.

It’s now almost four years since a seminal article in The Lancet identified climate change as the biggest global health threat of the 21st century. The projected future pattern of illness and disease now represents a significant challenge for NHS commissioners.

For the most part, commissioning in England has been dominated by short-term perspectives: achieving next year’s efficiency target or negotiating opportunistic shifts in the location of care. Only rarely is strategic change driven by robust public health analysis, even for predictable changes in demand arising from, for instance, rising obesity. Whether NHS commissioners at newly restructured organisations can rise to the task remains to be seen.

Sustainable styles of healthcare

What is clear, however, is that the quest for adaptation at the same time as dramatic carbon reduction calls for a different model of delivering healthcare. Not just hospital care, nor indeed NHS care, but the whole complex structure of health and social care provision.

Parts of the new model represent familiar wisdom. To reduce energy costs, use fewer buildings but use them more intensively. To reduce travel costs, for patients and carers as well as staff, offer more care at home or closer to home, and support it with advanced equipment and telecommunications. Exploit the potential of telemedicine.

Another dimension is reducing demand for hospital care by getting people to take personal health seriously: something approaching the Wanless report’s “fully engaged” scenario. The boundaries need to stretch beyond the NHS into private and third sector provision − a growing consumer of health resource − and crucially into the NHS supply chain. Crucial because the Sustainable Development Unit’s 2012 research on “carbon hot spots” for NHS goods and services identifies pharmaceuticals, including GP prescriptions, as the single biggest area to be targeted.

Pharmaceuticals account for 22 per cent of the entire NHS carbon footprint (see data attached), exceeding building energy use (18 per cent) and medical instruments (13 per cent). It’s an analysis that belies a knee-jerk “acute hospitals are the problem” thesis, and emphasises the importance of working across sectors. For reducing drug waste requires the cooperation of drug manufacturers, commercial pharmacy chains and prescribing GPs: none of them readily swayed by a Richmond House diktat.

‘There is so much opportunity to pursue more sustainable solutions in the health sector, we owe it to patients to make the most of them’

However, if this sounds complex, the NHS may find itself pushing against an open door, as the business case for efficiency and sustainability is attractive to commercial suppliers. No private provider wishes to burn energy wastefully; and the Sustainable Development Unit has found drug companies more than willing to help reduce packaging costs. Perhaps more significantly, major pharmaceutical and medical technology companies, in partnership with the NHS, have published the first ever international guidance on the carbon footprinting of their products.

Pursuing sustainability also offers a licence to think radically about other areas. Why not deliberately support local suppliers by procuring from nearby firms? Why not develop local self-sufficiency in recruiting staff? One of the strategic challenges facing all Western nations is where, in the long term, to source the staff to care for their ageing populations. It’s an interesting counter to the current trend for EU-wide competition and the growing dominance of huge outsourcing firms.

Culture ripe for change

Sir Neil McKay, chief executive of NHS Midlands and East, argues that the best starting point to drive sustainability up the management agenda − dominated by short-term survival − is not climate change but what’s right for the people the NHS serves. Redesigning clinical care is challenging, but there’s no contradiction between sustainability and productivity. “Deliver QIPP,” he says, “and the by-products will enable us to tackle climate change and sustainability.”

He insists that the Lansley reforms have created a culture ripe for change. He points to clinicians in both primary and secondary care feeling, at last, as if they have permission to talk to one another. He highlights the prominent role of local authorities, both in leading on public health and through ownership of health and wellbeing boards.

“There is so much opportunity to pursue more sustainable solutions in the health sector,” adds Sonia Roschnik, operational director of the Sustainable Development Unit, “that we owe it to our patients and the public to make the most of them.”

Noel Plumridge is an independent consultant and former NHS finance director

Downloads

Carbon hot spots data

Excelraw data ski jump

Excel

No comments yet