Read the full report from HSJ, in association with Allocate Software, on why patient safety should be the core business of healthcare

Why do we need another report?

Financially, ethically and professionally, patient safety should be the core business of healthcare. Yet despite big improvements reducing healthcare-associated infections and venous thromboembolism, why does patient safety still feel like something we are yet to crack? Where are the main areas to focus? And what are the first steps to improve?

“It is curious that people should think a report self-executive, should not see that, when the report is finished, the work begins” Florence Nightingale, letter to Mary Elizabeth Herbert (1863)

- Download a free PDF of the report

- More patient safety news and resources

- Kirkup: Morecambe Bay will happen again if underlying causes aren’t eradicated

One more report should do it…

If one more report were going to tip NHS patient safety into becoming a continuously self-improving system, it would probably have happened already. From Lord Darzi’s High-Quality Care For All in 2008(1) to the Berwick Review in 2013(2), mighty minds have reached similar conclusions. Yet it still seems that we are not there yet.

Contributors

- Writer Andy Cowper

- Martin Bromiley, chair of the Clinical Human Factors Group

- Caroline Clarke, deputy chief executive and finance director, Royal Free Hospitals Foundation Trust

- Andrew Foster, chief executive, Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh Foundation Trust

- Jonathan Hazan, chief executive, Datix

- Sir Bruce Keogh, medical director, NHS England

- Dame Julie Moore, chief executive, University Hospitals Birmingham Foundation Trust

- Dr Umesh Prabhu, medical director, Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh Foundation Trust

- Sir Mike Richards, chief inspector of hospitals, Care Quality Commission

- Simon Stevens, chief executive, NHS England

- James Titcombe, national adviser on patient safety, Care Quality Commission

So why should you read this report?

Five good reasons:

- Knowingly offering patients unsafe care is not just absurd, but morally and ethically wrong;

- Healthcare is a safety-critical industry, patient safety must be our core business;

- Greater transparency and focus on healthcare outcomes (neither of which will go away) will expose bad practice;

- Spending public money on remedying or compensating unsafe care is a massive, unjustifiable waste of our taxes and undermines confidence in the NHS;

- We and our families and friends could be the next ones affected.

None of these five reasons contain the phrases “national targets” or “£22bn efficiency challenge”. Why not?

Working with the grain

The reason is simple. If frontline staff don’t take the need to improve patient safety on board as their job, we won’t see the improvements needed. We’ll get far further faster by appealing to the motivation that first made these people choose a career in healthcare.

That motivation was to help sick people, by making them well, better or comfortable. And that motivation’s a perfect fit with encouraging and supporting them to make patient safety not just a priority, but core business: ‘the way we do things here’. (The number of these people originally motivated to achieve national targets or deliver financially motivated efficiency and productivity gains must be as close to zero as makes no difference.)

This is about broadening the group of people who see patient safety as the core of their job, from clinical directors and quality improvement leads to the entire team delivering healthcare. Getting patient safety right involves everybody.

Money matters

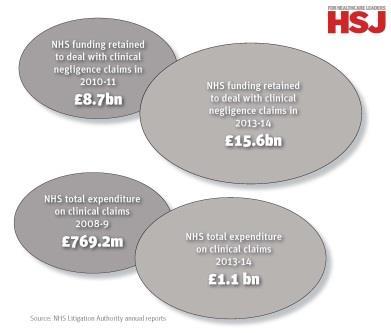

The business case for patient safety is best described as emerging, as we discuss below. Demand pressures and funding rises lower than the traditional annual 3-4 per cent are the reality. Using resources wisely matters massively.

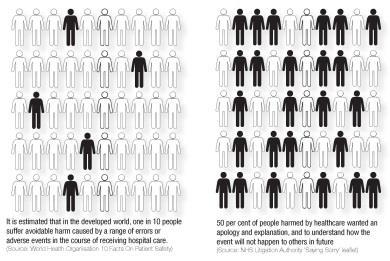

There is obvious waste of public money wherever avoidable harm is caused: both in burden of extra disease and in additional cost to rectify the error or omission. Ethics and efficiency strongly argue for safer care in the sense of getting it right first time and without waste.

There are evidence-based examples of patient safety cost-savings:

- Mental health Dr Juliette Brown and colleagues’ recent work(3) on reducing violence on older people’s mental health wards showed links to reduced costs.

- In wound care The “Stop The Pressure” campaign(4) evidenced a 50 per cent reduction in pressure sores in the NHS Midlands and East region in 2012-13.

- Frail older people’s care The Medical House Call Programme in MedStar Washington Hospital Centre saw improved quality, reduced hospital/ED use for common conditions and reduced Medicare expenditure(5).

- Cancer Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SAB) is a higher-dose precision radiation cancer treatment for non-small cell stage 1 lung cancer, which results in reduced, targeted treatment and also involved fewer hospital visits for cancer patients(6).

A priority for the health secretary

System leaders’ priorities matter: the NHS remains a hierarchical system. It can be actively helpful that safety is a key theme for health secretary Jeremy Hunt.

Speaking to the NHS Confederation’s 2015 conference, Mr Hunt called for the NHS (a system that successfully gives all UK citizens access to care) to become one which gives us access to quality care. Quality cannot be built without the firm foundation of safety.

‘System leaders’ priorities matter: the NHS remains a hierarchical system’

The health secretary is not in linear charge of the NHS, but remains a useful moral ally. Mr Hunt’s frequently stated admiration for the Virginia Mason hospital/health system in the US also saw him quote chief executive Gary Kaplan’s mantra that “the path to better care is the path to lower cost”.

Virginia Mason had a tragic safety incident in 2004: an antiseptic fluid was injected into patient Mary McClinton’s brain, killing her slowly. The hospital was open about the incident, making it the trigger to redesign all its processes to focus on safety. Following internal redesign, Virginia Mason’s outcomes and patient satisfaction improved markedly and its costs dropped considerably(7).

On 26 March 2014, in a speech at Virginia Mason Medical Centre(8), Mr Hunt announced an ambition to reduce avoidable harm in the NHS by half over the coming three years, saving up to 6,000 lives. Various initiatives aim to help achieve this:

- Inviting every NHS organisation to “Sign up to safety” and publicly list their plans for reducing avoidable healthcare-associated harms;

- Recruiting 5,000 safety champions as local ‘change agents’, identifying where care is unsafe and developing solutions;

- Creating a new Safety Action For England (SAFE) team to provide intensive support where it is most needed;

- Developing new, reliable measures of rates of avoidable death and severe harm in hospital, and assessing whether organisations are reporting the number of incidents that would be expected.

The NHS has sought to learn from Virginia Mason in a project started in 2006. The North-East Transformation Scheme(9) learned about lean methodology from the Virginia Mason network.

Surgeon and ex-health minister Lord Darzi defined safety as one of three domains of quality in healthcare, along with clinical effectiveness and patient experience. This translated into current policy as Domain Five of the NHS Outcomes Framework: Treating and caring for people in a safe environment and protecting them from avoidable harm(10).

Simon Stevens: where next on patient safety

As the NHS has become more transparent, we’ve seen what needs to be done to improve patient safety. In key areas this has already produced huge gains - think, for example, about the dramatic reduction in hospital-acquired infections.

But as we develop this agenda - building on the NHS Safety Thermometer, our new patient safety collaboratives, our 5,000 patient safety fellows and other linked initiatives - it is a good moment to take stock on where next on this vital journey. Three things strike me.

First, there’s a long list of clinical risks where, seen through the lens of patient safety, we have to act, and the NHS can be a world leader. There are still enormous gains to be had from improvements in areas such as sepsis and acute kidney injury. And one of the biggest threats facing all healthcare systems, anti-microbial resistance, needs to be comprehensively tackled as an emerging patient safety threat.

Second, we’ve got to broaden our safety focus across care settings, including the home. Yes, we’ve got to continue to pay close attention to clinical aspects of patient safety in hospitals, where the worldwide patient safety movement began, and support providers with continuing their focus on dignity and patient experience. But we’ve also got to think about the total patient experience across primary, community, mental health and social care.

Here’s a high-impact, real-world example: falls prevention. The NHS Patient Safety Thermometer recorded about 18,500 falls with harm last year. But as one in two people over 80 have a fall each year, that’s clearly a gross underestimate.

If we think about all the health professionals and statutory agencies visiting those people at home - community nurses, social care, fire service home safety checks, the occasional GP home visit - there’s a huge opportunity to coordinate a holistic approach to prevention, with shared frailty assessments and basic steps like ensuring safe rugs and slippers. That would also help tackle the £2bn a year cost to the NHS of falls.

Third, if we want to build a culture of safety throughout the NHS, the support functions for doing so need to be ‘owned’ by frontline health staff, providers and indeed patients - not imposed from on high, or driven by regulators or external national bodies.

The international experience shows the importance of embedding learning and support within care provision itself. We want a social movement of “done by and done with”, not “done to”. This needs to align with a more coherent system-wide approach to organisational development and provider improvement, which we’ll be setting out soon.

The NHS has got a lot to be proud of in the honest way we’ve begun squaring up to patient safety issues. As a result, care is measurably safer now than it was, say, three or four years ago. But our shared ambition has to be that in five years’ time it’ll be even better than it is today.

Caroline Clarke - How to develop or reinforce a safety culture

“There’ll already be people in your organisation working on quality improvement. Find them, work with them, train them if necessary. You don’t need fancy analytics: we already collect most data we need. You need consistent improvement methods: this may need a bit of resource; so will training staff to make safe care consistent across the organisation. This is particularly important if you’re over several sites. But it’ll pay back massively longer term.”

Sir Mike Richards - How to develop or reinforce a safety culture

“Depending on the organisation, developing a safety culture may not feel like picking low-hanging fruit, but it’s important hanging fruit! By encouraging staff to report incidents or near-misses in the right atmosphere and letting them know what’s changed as a result, safety issues will be properly addressed.”

The business case for patient safety

Writing ‘the business case for patient safety’ in the context of healthcare should feel absurd. The Hippocratic oath promises to “abstain from doing harm”. It should be hard to imagine a more safety-critical industry than healthcare, as airline pilot Martin Bromiley and former nuclear industry professional James Titcombe observe.

Martin Bromiley is a safety advocate and airline pilot whose wife Elaine was killed by medical error. James Titcombe is a former Sellafield project manager and currently Care Quality Commission national adviser on patient safety. He successfully exposed the truth over the death of his son at Morecambe Bay Foundation Trust following dysfunctional, inappropriate and unsafe midwifery care, leading to the Kirkup review.

Mr Bromiley suggests: “To justify efforts in this area, counter-intuitively you might first forget safety for a while, and just focus on the ‘business case’. A business trying to succeed has to be very good at what it does for clients; focus on what it should do to deliver what clients want; and focus on consistency and reliable delivery, and processes, systems and IT that support that.

‘“The NHS lacks the system basics on which to improve safety’

“Those are the basics. It also definitely helps to personalise the way in which your staff relate to you and each other, and train them and make it easy to treat the clients well.”

Mr Bromiley attributes the NHS’s uneven progress with patient safety to “the NHS trying to tackle safety for the past 15 years since 2000’s An Organisation With A Memory(11) without first putting in place those fundamentals of a successful business”. He says: “The NHS lacks the system basics on which to improve safety: a defined minimum level of performance, reduced variability, cost focus - all the process-driven basics of a good business, on top of which you can fiddle around. They’re slowly being put in place, but it’ll take another decade or so.”

Many experts interviewed agreed that despite various efforts, an unambiguous cut-and-dried, data-and-evidence-based business case for patient safety isn’t yet available. Indeed, several cited unsafely low levels of nurse staffing in hospitals as showing that worse care may, in the short term, be cheaper. Where care is unsafe due to a lack of resources (human or otherwise), safer care may appear to cost before it pays.

Organisations such as Virginia Mason or Salford Royal Hospitals Foundation Trust have shown significant financial improvements after a major campaign of quality improvement. Salford’s chief executive, Sir David Dalton, believes that his trust saves £5m and 25,000 bed days a year from its safety improvements since setting out in 2008 to become the NHS’s safest organisation(12).

Sponsor’s comment

How we organise the healthcare workforce today sits at the heart of what safe and sustainable care might look like for future generations. Health and care remains a people service. The opportunity, and risk, for safe care is executed at the interface between people, whether it is between teams within an organisation, or directly between those delivering care and those to whom they are delivering care.

At the same time, we cannot ignore that the workforce remains the single biggest cost for NHS organisations, representing 63 per cent of hospitals’ total spend last year. Everything suffers when a workforce is poorly deployed. Getting it right benefits safety, quality and finances.

While it may feel over the past few weeks that the pendulum is swinging from safe staffing to making savings, the reality is all organisations need to ensure they have the right people, with the right skills, in the right place at the right time, based on patient need.

Many of the workforce metrics that boards and wards should be continually reviewing serve both safety and savings objectives.

At Allocate, we advocate planning the workforce around the care activity that needs to be delivered. This means having timely information about patient numbers and need and it means having accurate details of availability and skills of staff. It also involves a more dynamic approach to matching these factors. Where the approach is embraced services are seeing both better budget management, less agency use and better outcomes.

Our workforce and governance solutions are used by more than 300 healthcare organisations in the UK to roster and plan nurses, doctors and others with transparency of safety and budgets. We are working closely with these organisations to help them unleash safety and savings benefits of having the right people, right place, right time.

Causation or correlation?

The unanswered question is whether these financial improvement were directly caused by the organisations’ safety improvements, or followed general improvements in organisations’ standards following the successful safety drive.

Some unambiguous financial gains from safer care exist. In 2013-14, the NHS Litigation Authority changed the way it prices indemnity cover so that providers with fewer and less costly claims pay less, creating an incentive for members to improve patient safety and reduce claims. The NHSLA also began to work more closely with trusts with higher levels of claims in order to support them to reduce harm and claims.

Caroline Clarke, deputy chief executive and finance director of the Royal Free London Foundation Trust and co-leader of the NHS Future-Focused Finance programme(13), suggests “a business case could be made for patient safety, perhaps not within one provider organisation but if you look at costs in an integrated way across the whole patient pathway”.

We must also remember that safety in healthcare is not an ‘acute hospital only’ matter. While contextual requirements and risks are different, we can no more neglect safety in primary, community and ambulance services - and particularly in mental health, as the NHS moves to make its parity of esteem with physical health less rhetorical and more a reality.

Five questions on how to improve safety

The Health Foundation’s 2014 briefing Reducing Harm To Patients suggested the following five questions that organisations should ask themselves to reduce avoidable harm to patients and improve safety:

- Do you have an agreed and explicit approach to continuously improving care that everyone understands?

- Do you have a systematic programme for building skills to enable staff to continually improve their services?

- Are senior leaders present on the shop floor, engaging staff and facilitating improvement?

- Do you have a system for measuring how safe you are, and the impact of any efforts to improve safety?

- Do you have open discussions about safety with patients and staff?

Julie Moore - How to develop or reinforce a safety culture

“Our work on improving drug compliance in UHB gave us good evidence that when we focused on relatively little things, bigger things improved at the same time. This is because your staff sharpen up their act and notice other problems and feel that they can sort them - and do. You need to allow people some freedom to think about their clinical practice (unless you’re desperately short-staffed, in which case very solid routine’s probably safer).”

Bruce Keogh - How to develop or reinforce a safety culture

“Getting managers interested in improving patient safety is vital to securing fast improvement. It worked with venous thromboembolism in hospital inpatients: the rate went from only assessing about 13 per cent of patients up to 90 per cent in just 18 months. And let’s keep a focus on the real patient safety issues: how to deliver safer care with seven-day services, and how to ensure safe care in hospitals for frail older people with multiple long-term conditions.”

Three key areas to improve safety

Researching this report, three vital areas repeatedly emerged:

- Design Shaping the system to allow for our human factors and frailties;

- Culture Embedding safety as a core business value of organisations; and

- Data Driving improvements with timely, user-friendly evidence of current performance.

Design

“We must not say every mistake is a foolish one” Cicero (De Divinatione II, 22, 79)

To err is human: we make mistakes. Dr Umesh Prabhu is medical director of Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh Foundation Trust, which has been nationally recognised for having made huge improvements in its quality and safety. He cites research showing that every human being makes between five and six errors a day.

Successful safety-critical industries know this, and have advanced systems to anticipate and prevent risk of harm. Prominent figures in the patient safety movement have professional backgrounds in such industries: aviation in the case of safety advocate Martin Bromiley; and nuclear power in the case of CQC national adviser on patient safety, culture and quality James Titcombe.

Such safety-critical industries place great importance on designing systems and processes that, in Titcombe’s memorable expression “fail to safe: when things go wrong or people make errors, the design reduces as far as possible the risk that harm will follow”.

Mr Bromiley thinks the NHS must “protocol-ise, standardise and set minimum standards of performance” to improve safety and consistency.

Human factors and human error

The importance of this kind of design, referred to by some as “human factors”, has been recognised in healthcare for some time. Martin Bromiley founded and chairs the Clinical Human Factors Group14, which aims to advance the cause of safer system and process design to minimise the risk of patient harm(15).

A concise blog on human factors’ development in the NHS by CHFG adviser Professor Jane Reid(16) outlines “human factors’ main aim [is] to optimise human performance by understanding the interface between humans, their environment and equipment”.

Top-down hectoring approaches urging care providers to cut out errors are probably of less value than one which seeks to enable them to understand the root causes of avoidable harm. These will often be down to human error, facilitated by poorly designed systems and processes.

Culture

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast” Sign on boardroom wall of Ford Motor Company’s US headquarters, attributed to Peter Drucker and popularised by Ford president Mark Fields

“Culture is what people do when no-one is looking” Gerard Seijts(17)

Sir Mike Richards, chief inspector of hospitals for the Care Quality Commission, says that “a safety culture is one of the main things we’re looking for” in CQC inspection. He defines a safety culture as including “not only an encouragement to report incidents, but whether the trust has a system for feeding back to staff who report incidents on actions they’ve taken to prevent a repeat. Another aspect is having a genuine learning culture: currently, safety culture is very variable”.

‘Trusts who do well in inspections tell us upfront where their issues are’

While CQC inspections use national data on healthcare-associated infection rates, Professor Richards is not always convinced by local hand hygiene audits: “We prefer to use our own eyes. Do we see staff wash hands between every patient contact?”

He cites checking not only whether mandatory training is being delivered, but accessibility and maintenance of resuscitation kits, “not because they’ll necessarily be needed often, but if they’re where they should be and maintained as they should be, it’s a sign of a safety-conscious organisation”.

James Titcombe agrees that self-knowledge is often a positive sign of a safer culture: “Trusts who do well in inspections tell us upfront where their issues are. That’s usually associated with an open and supportive culture. A safe, well-run organisation will know where its issues are: if you have quality issues, know you have them and are acting on them, that’s a good indication to the CQC that an organisation is well led with effective governance arrangements in place.”

Professor Michael West’s work on developing high-quality and safe cultures(18) emphasises the clear evidence that satisfied staff teams provide higher-quality, safer care. West emphasises six key points:

- Prioritising an inspirational vision, focused on high-quality care;

- Clear aligned goals and objectives at every level;

- Good people management, health and wellbeing for flourishing;

- Employee engagement throughout;

- Team and inter-team working;

- Values-based leadership at every level.

‘Just accountability’ versus ‘no blame’

Mr Titcombe is clear that the covering up and collusion outlined in the Kirkup report into Morecambe Bay was as bad as the poor-quality clinical care: “To err is human, but to cover up is unforgivable.”

A “no blame” culture for the NHS is often advocated, but most participants in this report were uncomfortable with this phrase. Dame Julie Moore, chief executive of University Hospitals Birmingham Foundation Trust, says: “We prefer the term ‘just accountability’ to ‘no blame’. Because it’s fortunately rare, but sometimes there is blame, and someone has done something seriously wrong - and you’ll stand no chance to develop a safety culture if that person can say: ‘Well, you can’t take action against me because we’ve got a no blame culture.’”

‘To err is human, but to cover up is unforgivable’

James Titcombe agrees that “the NHS has to get much better at separating negligence or recklessness, where blame would be appropriate, from honest mistakes, where blame is unhelpful. It’s vital to get this differentiation right, because a ‘point the finger’ blame response is cheap, easy, quick and spreads fear of reporting things - and so is deadly to patient safety.”

Datix chief executive Jonathan Hazan thinks that we need to consider the “just culture” described by US author David Marx in Whack-A-Mole: The Price We Pay For Expecting Perfection(19) has been counter-productive to helping society deal with the risks and consequences of human error.

The right leadership

Umesh Prabhu agrees that openness about problems is essential to improving patient safety. Dr Prabhu says that starting the improvements at Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh Foundation Trust was not hard “because of our chief executive Andrew Foster’s commitment to doing the right thing for patients. There was no denial that we had safety problems, and also cultural problems. We decided that, working with our staff, we needed to define the values, culture and behaviours we wanted to see from our leaders and managers”.

Dr Prabhu attributes the trust’s patient safety improvements directly to this cultural change and robust staff engagement: “We did have to change some bullying leaders and some leaders who were too nice to their clinical colleagues, and removing them empowered staff to speak up: they saw that we meant what we said.

“Our values were about openness and honesty, and no bullying or covering up, and support for our staff as well as for patients and their families. Those who didn’t comply with these values were given a chance to change, and if they didn’t change, they had to step down as leaders and managers.

‘Leaders have got to walk the floors in their organisations, and know and be known by their staff’

“We also have robust governance, through which we identified few consultants with behavioural issues: all have been challenged, and all of them have changed or have left the organisation. Most staff with behavioural problems need help and support; not blame, discipline, humiliation or punishment. It is all about nipping these behaviours early and effectively, so that we have a culture where all staff are able to speak up, and when they do we act.”

Dame Julie Moore concurs about the risk of poor leadership driving the wrong culture: “Leaders have got to walk the floors in their organisations, and know and be known by their staff, and talk to them. Often. And ask them where care could be safer; ask them what’s preventing them from delivering safer care now, today.”

Some years ago, University Hospitals Birmingham had a major initiative on ensuring that inpatients received the right drugs in the right dose at the right time, and had to redesign timing of ward rounds and meals to ensure this happened.

Missed doses or drugs out of stock had to be notified. “By making and maintaining a fuss about ‘right drug, right dose, right time’, you as a manager show your clinicians that you care about the little things that matter to safe, quality care,” Dame Julie concludes.

The NHS statutory duty of candour

Since November 2014, CQC-registered NHS provider bodies must comply with a new statutory duty of candour. (Independent sector health providers had to comply since April 2015.)

Duty of candour involves giving patients accurate, truthful, prompt information when mistakes are made and treatment does not go to plan.

It includes:

- Recognising when an incident occurs that impacts on a patient in terms of harm;

- Notifying the patient something has occurred;

- Apologising to the patient;

- Supporting the patient further;

- Following up with the patient as your investigations evolve;

- Documenting the above discussions and steps.

Prominent anthropologist Clifford Geertz(20) wrote in The Interpretation Of Cultures that culture is “the ensemble of stories we tell ourselves about ourselves”. If we accept this definition of culture, then we must begin any change by consistently telling ourselves better and safer stories about ourselves.

Data

Clinicians are the people who deliver patient care. Their training predisposes them to respond better to data and evidence. So timely feedback with manageable amounts of user-friendly data on safety and quality is likely to be a powerful motivation tool.

Evidence can move mountains fast, as NHS England’s medical director Sir Bruce Keogh reflects. Sir Bruce’s review of the trusts that topped the list of mortality outliers21 was a recent chapter in a career which has also produced seminal work with Ben Bridgewater on publishing cardiac surgeons’ outcome data22 This evidenced consistent improvement and no avoiding of “high-risk” patients by surgeons following publication. Last November, NHS England published data for individual surgeons in 10 specialties(23).

The Royal Free’s Caroline Clarke “got into using data to drive the improvement through quality improvement methods. It’s vital to work with your clinicians to decide what you’ll start to measure for safety and QI: do it from the front line, not top-down”.

Ms Clarke quotes Harvard academic Richard Boehmer’s four habits of high-value healthcare organisations(24):

- specification and planning;

- infrastructure design of microsystems;

- measurement and oversight; and

- self-study.

The importance of design and data in all of these areas is evident.

UHB’s Dame Julie emphasises the need to “look at a pile of benchmarking data. Even if you think you’re a very good trust, don’t kid yourself: you’ll always find errors”.

Jonathan Hazan, chief executive of safety incident reporting software firm Datix, emphasises the importance of not only collecting the safety data but feeding back on progress. “The two complaints I hear most often about Datix are one: ‘The forms are too complex, and take too long to complete’; and two: ‘We don’t get feedback after we report a safety incident or near-miss’. Our software enables feedback mechanisms, but trusts need to put the systems, processes and people in place to make that happen and make reporting feel worthwhile.”

The NHS Litigation Authority

The NHS Litigation Authority has a variety of vital roles in patient safety. It provides indemnity cover for legal claims against the NHS, assists the NHS with risk management, shares from claims and provides other legal and professional services for members.

In March 2014, the NHSLA ended its old risk management assessment, which focused on rigid standards and assessments. It replaced it with a Safety and Learning Service that actively supports NHSLA members to reduce harm and improve patient safety.

NHSLA’s Safety and Learning Service includes:

- Information and analysis in relation to your organisation’s claims data on a new secure extranet;

- A safety and learning library of best practice guidance including case studies derived from root cause analyses of the national database of claims, thematic guidance and useful links;

- Local network events to support members and network them with other organisations;

- Targeted workshops for a number of key groups; boards and leaders to help prioritise activity related to reducing claims, risk and claims managers and clinicians;

- A Safety and Learning newsletter which lets providers know about the local events, workshops and webinars.

Research for NHSLA(25) found that 50 per cent of people harmed by healthcare wanted an apology and explanation, described in its Saying Sorry(26) publication.

Andrew Foster - How to develop or reinforce a safety culture

“If you find a poor safety culture in an organisation, you may have to use a shock tactic of confronting staff with data and facts to break through any denial or ‘that’s the way it is here’ syndrome. But that won’t work on its own: alongside, you have to offer them help and support to improve. Get them excited and enthused about improving safety. Be consistent in focusing on it. And ask them where the unsafe services are: they know.”

Umesh Prabhu - How to develop or reinforce a safety culture

“If you want to know where the bad leaders and unsafe services are, talk to your staff! They always know (the bad leaders are famous) - but they need to feel safe to speak to you. Genuinely engage with your staff, and giving them real opportunities to speak up and be and feel heard: these things are crucial. So is acting on what they tell you: if you have bad leaders with bad values, you have got to remove them.”

James Titcombe - How to develop or reinforce a safety culture

“Incentivise reporting of incidents and near-misses. Medical schools and training need to start promoting and normalising this at the start of clinicians’ careers. In the nuclear industry, it was ingrained from day one: at appraisals, you’d have to demonstrate a time you’d raised a safety concern. If you couldn’t, people started to wonder about your professionalism.”

Bibliography

1 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085825

2 www.gov.uk/government/publications/berwick-review-into-patient-safety

3 http://qir.bmj.com/content/4/1/u207447.w2977.abstract

4 http://nhs.stopthepressure.co.uk/whats-happening.html

5 www.medstarwashington.org/2015/06/18/a-proven-model-national-demonstration-validates-treating-frail-elders-in-their-home-saves-in-medicare-costs

6 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/24951606/

7 www.virginiamasoninstitute.org/books

8 www.gov.uk/government/speeches/sign-up-to-safety-the-path-to-saving-6000-lives

9 www.nelean.nhs.uk/about/

10 www.england.nhs.uk/resources/resources-for-ccgs/out-frwrk/

11 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Aboutus/MinistersandDepartmentLeaders/ChiefMedicalOfficer/ProgressOnPolicy/ProgressBrowsableDocument/DH_5016613

12 www.kingsfund.org.uk/david-dalton-may2012.pdf

13 www.futurefocusedfinance.nhs.uk/

14 http://chfg.org

15 http://chfg.org/resource/human-factors-theory

16 www.nhsproviders.org/blogs/jane-reids-blog/what-human-factors-can-teach-the-nhs/

17 www.business-standard.com/article/management/culture-is-what-people-do-when-no-one-is-looking-gerard-seijts-112092400046_1.html

18 www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_document/michael-west-developing-cultures-of-high-quality-care.pdf

19 www.whackamolethebook.com

20 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clifford_Geertz

21 www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/bruce-keogh-review/Pages/published-reports.aspx

22 http://heart.bmj.com/content/early/2010/05/29/hrt.2010.194019

23 www.england.nhs.uk/2014/11/19/outcome-publication/

24 www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1111087

25 www.nhsla.com/Safety/Pages/HelpfulTools.aspx

26 www.nhsla.com/Claims/Documents/Saying%20Sorry%20-%20Leaflet.pdf

Resources and tools

Darzi WHO Safer Surgery checklist

Francis www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com

Berwick www.gov.uk/government/publications/berwick-review-into-patient-safety

Government response www.gov.uk/government/publications/mid-staffordshire-nhs-ft-public-inquiry-government-response

National responses/initiatives www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/patientsafety/

- Launching a new National Patient Safety Alerting System (NPSAS);

- The monthly publishing of data on never events;

- Publishing of key patient safety indicators by hospital on My NHS (NHS Choices);

- Launching the Patient Safety Collaboratives;

- Developing an initiative with the Health Foundation to recruit a network of 5,000 Patient Safety Fellows.

Resources

National Patient Safety Agency resources now in NHS England - Seven Steps (www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/collections/seven-steps-to-patient-safety/)

NHS Safety Thermometer (www.safetythermometer.nhs.uk) (www.institute.nhs.uk/safer_care/harm_free_care/harm_free_care_homepage.html)

Recording

www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/patient-safety-data/organisation-patient-safety-incident-reports/directory

Using data

NHS Operating Framework (Domain 5: Treating and caring for people in a safe environment and protecting them from avoidable harm) on the NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/webview

Clinical review: All patient safety incident reports submitted to the NRLS categorised as resulting in severe harm or death are individually reviewed by clinicians at NHS England to make sure that maximum learning is extracted from these incidents, and, if appropriate, action can then be taken at a national level.

Health Foundation www.health.org.uk/areas-of-work/topics/patient-safety

9 Readers' comments