- The HSJ/HCL Workforce Investigation studied the underlying causes of the NHS’s escalating clinical temporary staff bill

- Chief executives, human resources directors, medical and nurse directors and finance directors were surveyed, with more than 70 responses.

- Recommendations include enhanced pay for shortage specialties and offering more flexible working

- Download a PDF of this report

The NHS has an urgent need to reduce its £3bn plus dependency on temporary agency staff. This investigation explores the causes and looks for possible solutions

Author’s introduction

Clare Panniker’s foreword to this investigation sets out the challenge for the NHS succinctly and starkly: in a period of relative economic scarcity, ongoing pay restraint and the parallel need to shift care into new settings, the NHS has an urgent need to reduce its £3bn plus dependency on temporary agency staff.

This HSJ/HCL investigation represents an attempt, first, to analyse the extent of the problem and, second, to look within the NHS to find potential answers to address it.

Some of those answers involve improvements to existing systems and processes. Some involve centrally driven solutions, and others involve grasping

the opportunity offered by examples of innovative approaches found in local NHS organisations.

No single example offers a lone solution and none will bring overnight results. But we hope that, taken together, they point to ways the NHS can curtail its spiralling agency costs and invest savings instead in a permanent workforce fit for the future.

Sally Gainsbury is a journalist and senior policy analyst at the Nuffield Trust. She wrote this investigation in a personal capacity

About the investigation

This investigation was launched following government announcements of a crackdown on “rip off” NHS agency spending. HSJ and HCL Workforce Solutions commissioned Sally Gainsbury, senior policy analyst at the Nuffield Trust, to investigate the underlying causes of the NHS’s escalating clinical temporary staff bill, to gain a better understanding of current practice, and to look inside the NHS for potential solutions.

The investigation was the brainchild of Claire Billenness, a managing director at HCL Workforce Solutions, a leading provider of temporary and permanent clinical staff to the NHS. HCL also works with NHS organisations to improve their human resource management, including reducing their reliance on temporary agency staff through the managed services division HCL Clarity.

Sally Gainsbury is a former Financial Times journalist and HSJ news editor, who works as a senior policy analyst at the Nuffield Trust think tank. She completed this work in an independent capacity.

The problem

In the 11 years between April 2004 and September 2015 the proportion of the foundation trust pay bill spent on agency and contract staff more than doubled, from 3.5 per cent to 7.2 per cent. That is the equivalent of over £2bn annual expenditure in the foundation trust sector alone.

It is not possible to reliably compare expenditure by NHS trusts on agency spending over time but halfway through the current financial year, their spending on agency and contract staff had reached 8.5 percent of their total pay bill, indicating that across the provider sector, the NHS is on track to spend in the region of £3.6bn on temporary staff in 2015-16.

As figures from the consolidated foundation trust accounts show, the growth in the proportion of salary costs spent on agency staff in the past 10 years has followed upward steps, interspersed with periods of only very modest reduction or recovery (see chart 1 – below).

The specific drivers behind the current step differ between staff groups, geographical region and provider type. But at a summary level, the problem can be described as simply an excess of demand over supply. Put simply, there is a shortage of staff willing and able to work at standard NHS terms and conditions.

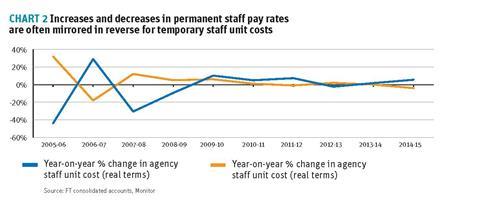

Two further charts illustrate the underlying problem. From the foundation trust accounts again, chart 2 shows the year-on-year percentage change in the average unit cost of full time equivalent employed staff and of their agency equivalents.

From the wildly fluctuating first few years – as the new consultant contract and Agenda for Change deals were implemented – to the steadier last five years, a pattern emerges: one where increases in employed staff unit costs are mirrored by decreases in bank and agency rates, and vice versa.

In 2014-15 alone, average employed staff unit costs at foundation trusts fell by 3.8 percent in real terms to £43,416 while the average unit cost of agency staff rose by 5 per cent to £91,890.

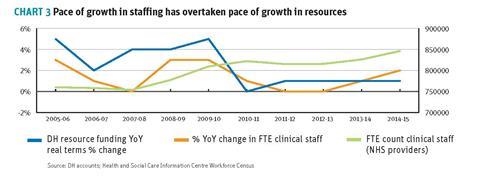

Chart 3 dramatically illustrates the NHS’s problem: while the Department of Health’s resource funding has slowed from year-on-year real terms growth rates of between 4 and 5 per cent until 2009-10 to often less than 1 per cent from 2010-11 – where it is set to remain for the next five years – the NHS’s demand for clinical staff has continued to rise, crossing the line to exceed the pace of growth in funding from 2013 onwards.

The available data is far from perfect: There is a lack of consistency in NHS accounts around the reporting of spending on bank staff, with their whole time equivalent numbers only being reported separately since 2013-14.

Reported headline figures on temporary staff costs for 2014-15 therefore vary between £3.3bn and £2.9bn depending on whether spending on employees engaged through providers’ own “banks” of staff – typically at rates much closer to standard NHS hourly rates – are included.

The problem can be described as simply an excess of demand with a lack of staff willing and able to work at standard terms

This lack of clarity – the absence of a “single truth” as one NHS regulatory source put it – is both a symptom and a driver of the problem. It is evident at the micro level of individual organisations struggling to plan day-to-day ward or service staffing needs as well as at the national level where huge gaps that have emerged in training posts in clinical specialties and qualified nurses.

However, it is clear that whichever accounting figure is used, NHS spending on temporary staff is growing at an unsustainable rate, with spiralling agency costs highlighted as the single biggest contributor to the projected £2bn-plus NHS provider deficit expected this financial year.

National action

Political focus on the cost of NHS temporary staff coincided this year with the summer government spending review, bringing with it political heat including an as yet unpublished Cabinet Office “deep dive” investigation of the issue.

In August, NHS economic regulator Monitor (now NHS Improvement) announced its intention to effectively ban the use of staffing agencies outside of approved price and contractual frameworks and to impose steadily reducing ceilings on the proportion of provider salary expenditure on nurse agencies.

The regulator also proposed a cap on the hourly rate of nursing staff. HSJ understands that concerns about the medical locum market – essentially the likelihood that significant proportions of locums would simply not work for capped rates as well as the risk of creating geographical medical shortages due to the highly mobile nature of some locums – had originally led Monitor to rule out the extension of such a cap to medics.

Despite such concerns, October 2015 saw the DH announce its intention to press ahead with price caps covering all staff categories, including locum doctors.

These caps, the department claimed in a press statement, would “remove £1bn from agency spending bills over three years”, enabling reinvestment in patient care.

The move was accompanied by the potentially complementary move by the Home Office to add nursing to the shortage occupation list for international immigration, albeit only as a temporary measure pending further investigation into supply shortages for nursing staff.

Although the new capping rules initially apply only to providers that get emergency resource funding from the DH, or those in financial breach of the terms of their licence, the regulator has made it clear these stipulations will be absorbed into its value for money assessment applicable to all NHS providers.

This effectively imposes the agency caps on all NHS providers – although with the important and significant caveat of clauses that allow providers to override the rules on grounds of patient safety.

But while the DH heralded £1bn savings from the capping measures, Monitor’s impact assessment was less certain. Carrying the tell-tale warning of “time limitations in preparing this impact assessment” the regulator estimated maximum annual savings at around £200m and warned that, even with an initial cap set at 150 per cent of standard NHS pay rates, around 50 per cent of employers could be forced to breach the maximum rate in order to safely staff services if locums simply refused to work at cap rates.

The regulator was more optimistic for nursing caps yet still assumed the most likely scenario was 70 per cent compliance.

Current state of play

To understand how providers were experiencing and dealing with the temporary staff problem, HSJ invited selected chief executives, human resource directors, medical and nurse directors and finance directors to take part in a survey throughout November, which received over 70 responses.

We asked participants to indicate the staff groups where they most needed to turn to agencies. For nursing staff, the overwhelming pressure was for band 5 nurses, with just under three quarters of survey respondents reporting band 5 nurses as their biggest pressure point. Just over one in 10 respondents also cited band 6 nurses as a significant pressure, with the reported demand for healthcare assistants and higher band nurses significantly lower.

For medics, the picture was less uniform. Just over a third of providers ranked consultant grade medics as their biggest pressure point for agency staffing, with a quarter ranking instead staff grade or specialty doctors.

As with nursing staff, respondents were asked to rank staff groups according to the degree of pressure. When the two highest ranked groups were considered, there was an almost equal split among respondents in demand for consultants, specialty doctors and registrars – perhaps indicating providers’ pragmatic response to consultant shortages by filling consultant gaps with senior doctors in training, or doctors who have come off the formal training ladder.

Providers consistently ranked acute medicine, A&E and care of the elderly as pressure points for both nursing and medical staff

Asked to identify specialties with the most severe staffing gaps, providers consistently ranked acute medicine, A&E and care of the elderly as pressure points for both nursing and medical staff. Although this report focuses on acute hospitals, inpatient and community mental health were also frequently mentioned as areas with shortages for both nursing and medical staff. Turning specifically to nursing shortages, respondents indicated that general surgery, critical care and A&E were significant pressure points, while for medical staff, respondents ranked general surgery, paediatrics and gastroenterology as other problem specialties.

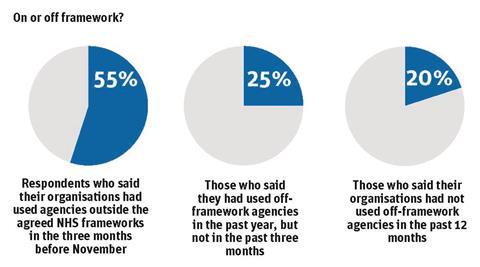

For these clinical staffing needs, just over half of respondents reported that their organisations had resorted to agencies outside agreed NHS frameworks in the past three months. A quarter reported that although they had used off-framework agencies in the past year, they had not used them in the three months prior to the survey date.

Although that timing loosely coincides with the announcement of national measures to cut agency staffing, the period concerned includes summer – and so could also reflect lower demand over those weeks. A fifth of respondents said their trusts had not used off-framework agencies for at least a year.

National shortage

Asked to identify the drivers behind demand for agency staff, between half and two thirds of respondents indicated that the strongest was national level staffing shortages. Other key drivers were unpredictable (or poorly predicted) levels of demand and the focus given to safe staffing levels by the Francis report following the inquiry into failings at Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust.

A fifth of respondents listed the need for one-to-one care (“specialing”) for specific patients or staff sickness as significant drivers affecting their organisations, while just under a quarter highlighted local recruitment difficulties such as reputational problems for individual organisations, or their proximity to more attractive centres of employment.

The singling out of the Francis report as a driver is significant because it echoes in part a belief in some quarters of Whitehall that NHS hospitals responded to the Francis report by rapidly inflating their staffing requirements – much of it through the use of agency staff.

The belief also often accompanies the assumption that such staffing requirements are based on crude nurse to bed ratios – such as “one in eight” – which fail to adequately reflect both patient acuity and staff skill mixes.

Impact of Francis

Yet this characterisation is not borne out by the survey responses. Asked how their organisations determined safe staffing levels, less than a third of respondents referred to national guidelines or staff ratios.

The majority – just under two thirds – reported using acuity tools such as the Shelford Group’s safe staffing tool, which most said was used as part of a triangulation process bringing in ward-level intelligence and benchmarking, typically reviewed every six months. A minority – slightly more than one in 10 – said they used e-rostering systems.

While these findings suggest room for improved use of technology in assisting providers to manage permanent staffing better, they do not suggest organisations resorting to knee jerk or simplistic ratios.

Although few doubt the significance of the Francis report in increasing demand and staffing numbers, the chief executive of one district general hospital summarised the position of many: providers have not assessed their levels of staffing needs any higher in relation to patient acuity, but rather they are now more likely to take action to fill staffing gaps when they are found wanting – particularly after the Francis report led to the requirement for hospitals to publish monthly ward level staffing levels and fill rates.

“We publish monthly nurse numbers by ward and day and night shift. So there is greater scrutiny at the time when the avenues to recruit are reduced,” the chief executive said.

“That’s created a market for temporary staff… If you say you will have four staff in and you have one vacancy and then one staff calls in sick – before Mid Staffs there might have been some muddling through; but it’s much harder to do that if you have said we need ‘this many’ staff.”

Capped rates

The survey also asked participants to assess their organisation’s ability to comply with the regulator’s hourly price caps for agency staff and focused on the second “ratchet” of cap rates scheduled to be imposed on 1 February next year. From then, caps will be set at 100 per cent above maximum NHS pay rates for junior doctors and 75 per cent all other clinical and medical staff.

Just over half of respondents reported their organisations were either “unlikely” or “uncertain” to meet those capped rates for band 5 nurses, staff grade doctors and for consultants.

Respondents were most optimistic about their ability to meet the February cap rate for band three clinical support staff and for junior doctors – although the proportion of those either certain or cautiously optimistic they could meet cap rates for these staff was still less than half.

Moreover, the survey also highlighted a danger that, for some organisations, the capping regime could see increased temporary staff costs as around one in 10 organisations are already paying rates below the level of the second planned ratchet.

The results highlight that although national measures could be helpful in places, local initiatives and improved management processes will also be necessary.

What are providers doing?

Many providers are clearly in a precarious position on temporary clinical staff. This underlines the need for local actions as well as national measures to help the NHS wield its collective buying power to drive down agency costs.

To gather intelligence on what providers are doing locally to reduce the need for temporary staffing we scanned board reports, national best practice and guidance; interviewed senior directors and NHS leaders; and received written submissions. Common initiatives and measures were then fed back into our targeted survey in order to better understand the extent to which measures were being adopted across the service.

This resulted in a menu of 22 different measures that we presented to survey participants.

The sheer volume of nurses leaving the NHS due to their need for a more flexible working life means providers are right to make this a priority

We then asked if these were being implemented, planned for imminent implementation or had been rejected as irrelevant to their organisation or unworkable for other reasons.

The results indicate significant actions are already being taken. Ninety per cent of respondents said their organisations had either already implemented or were planning to implement a range of measures including skill mix review, introducing or extending an in-house bank and introducing e-rostering software.

A slightly smaller proportion said their organisations were planning, or had already undertaken reviews of nurse shift patterns; the introduction of more flexible working patterns to recruit and retain staff; and reviews of sickness absence and annual leave.

While the avalanche of interest in e-rostering systems will be welcomed by the members of the Carter review team, who have found the NHS could make substantial savings by not only installing e-rostering systems but also using their full functionality – employer attempts to better manage staff sickness and to offer more flexible working could also be significant.

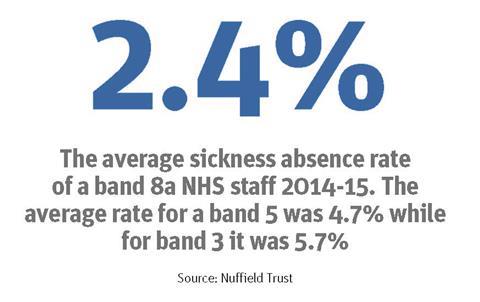

Nationally, band 5 nurses have a sickness absence rate almost twice that of band 8a clinicians – whose ranks include patient-facing employees such as advanced nurse practitioners and nurse consultants.

While many organisations report their sickness absence at board level, most do so only at an aggregate level and so miss the opportunity to identify significant discrepancies either between staff groups and grades or between clinical divisions and target improvement initiatives and interventions effectively.

Analysis by Central Manchester Foundation Trust, for example, found strong correlations between divisions with the highest rates of sickness absence, those undergoing major change processes and those with the highest staff turnover and vacancies. The insight has enabled the trust to reduce its sickness absence rates by focusing efforts both in terms of managing staff on long term or frequent sickness absence and in prioritising efforts to shorten time delays in recruiting to vacant posts in highly pressured divisions.

Responding to employee demands for increased flexibility is more challenging to providers, however, particularly as many also cite the reluctance of nursing staff to work weekend shifts and other antisocial hours as a driver behind their use of agency staff. The move to seven day working also presents a challenge in this area.

However, the sheer volume of nurses leaving the NHS due to their need for a more flexible working life means providers are right to make this a priority area in their attempt to reduce their reliance on temporary staff.

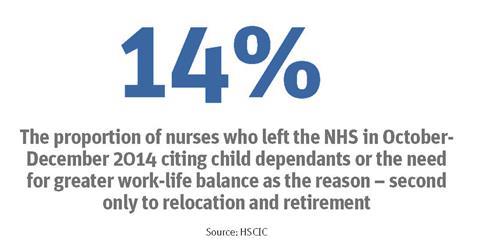

Health and Social Care Information Centre statistics show that between the third quarter of 2011-12 and the same period in 2013-14, the number of qualified nurses leaving the NHS citing either childcare commitments or the need for a better lack of work-life balance more than doubled to 1,720 – equivalent to some 7,000 a year, or two thirds of the current number of full time equivalent nurse vacancies.

HSJ is aware of initiatives in individual organisations to develop “super flexible” term time only contracts as well as “passport contracts” that would allow staff to work across a cluster of organisations in the same conurbation on common terms – although such plans are at an early stage.

The survey also indicated that over two thirds of providers are either already implementing, or plan to implement by the end of this financial year, the following to address their reliance on temporary clinical staff:

- Controls to require additional levels of management sign off on agency bookings Such controls have been recommended by Monitor/NHS Improvement’s Agency Intensive Support Team. Responses vary between requiring sign off from an on-call member of the executive management team to weekly ward-by-ward scrutiny of actual agency use.

- Review of medical staff job planning Actions here include reviewing existing job plans as well as the process for agreeing plans and also making variation between individuals and divisions more transparent.

- Introduce new systems to share spare nursing capacity between wards Actions vary between deploying new technology to provide real time alerts to daily or even six hourly cross- division meetings to share information on daily staffing levels.

- Working with local education and training providers to offer career pathways into nursing for support staff Britain’s economic recovery from recession has seen an about-face in trusts’ ability to recruit and retain healthcare assistants. Such staff now demand clear career trajectories to enable them to follow a path into higher paid and higher skilled work.

- Extending and improving the use of existing e-rostering software Lord Carter’s report leads the call to arms in this area, which the majority of providers are now taking up. However, significant investments in staff training and ongoing time are required to use these systems at their full capacity.

- Introducing new posts to ease some of the medical workload Roles such as physician’s assistants have always been surrounded by controversy, but an increasing number of providers (over two thirds as indicated in our survey) now plan to ease medical workload by introducing innovative posts.

International recruitment, both of medics and of nursing staff, is also being actively pursued by over half of providers, alongside increases to pay rates for shifts worked through internal nursing banks.

Equally interesting is the range of measures which, while being implemented by some, have been reviewed and rejected by a significant proportion of other providers.

These include the use of blanket bans on agency bookings for certain clinical grades, such as healthcare assistants, or across entire clinical areas.

Although two thirds of respondents said their organisation had such a policy (falling to a third for area-wide bans) an almost equal proportion said they had considered the move but rejected it – indicating the degree of sensitivity providers have towards ensuring safe staffing levels are maintained despite escalating pay costs.

Providers are even more split over offering enhanced pay rates to clinicians and medics. Around a third say they are now offering enhanced rates to shortage specialties, but an equal number have rejected the proposal.

This indicates that, while clinical supply shortages may be seen and analysed through a supply and demand lens – driven by falling pay rates for permanent staff – providers are either reluctant, or unable, to respond in a purely economic way.

Innovation and recommendations

Despite evidence of widespread action to reduce reliance on temporary clinical staff, the fact remains that over the course of the first six months of 2015-16, the proportion of the total NHS provider pay bill spent on agency staffing increased.

It is clear, then, that more radical approaches are also needed. This investigation’s attention has been drawn to the following innovative schemes discreetly under way in parts of the NHS that could be widely replicated and adapted.

Nearly all of them have one factor in common: they face up to the very real problem of national shortages by growing their own supplies of qualified doctors and clinicians.

The Derby Royal experience: a fourfold increase in A&E doctors

The shortage of emergency medicine doctors is well known. The Royal College of Emergency Medicine puts the current shortfall of consultants alone at 400 and estimates the cost of engaging locum emergency medics at over £150m – more than the total salary cost of all directly employed emergency medicine consultants.

These shortages are felt both at consultant and at junior doctor level, where there is an absence of doctors opting to train in emergency medicine.

The beauty of Royal Derby Hospital’s scheme is that it addresses both short and long term supply problems for emergency medicine by offering access to specialist training and rotations for staff and associate specialist (SAS) doctors – a group of doctors who would otherwise find their career progression towards consultant blocked through the inability to access specialist training rotations.

By developing a programme of three-month secondments in relevant specialties such as anaesthetics, intensive care, acute medicine and paediatrics, alongside protected study time and consultant supervision, Derby offers SAS doctors the chance to work towards consultant registration.

In so doing, Derby has successfully increased the number of whole time equivalent SAS doctors working in its emergency department from 4.8 to 21 in just 18 months.

Calculated savings – based on converting locum spend into substantive posts – are just under £1m.

The scheme is already being adopted by other East Midlands providers – allowing consultant supervision and training to be shared between sites.

RDH emergency medicine consultant Dan Boden says there is ample opportunity for wider replication across multiple specialties and sites.

The Lancashire and Bolton experience: self-funded nursing students with loyalty lock

While Derby has been growing its own future emergency medicine consultant workforce, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals has been at the forefront of a shift to self-funded nursing degrees, getting around the limit on nurse degree places commissioned by Health Education England.

The scheme is particularly noteworthy in light of the Chancellor’s November autumn statement, which announced plans to end HEE’s direct funding of nurse degree programmes by 2021, switching financing for tuition fees and student living costs instead to the Student Loans Company.

In addition to an eventual annual saving to the DH of £1.2bn, the government hopes the move will see a significant increase in the number of degree places available, as universities respond to the liberalised market and expand courses.

These national-level changes will not begin until September 2017 – but Lancashire’s first cohort of self-funded student nurses started their studies in partnership with Bolton University in February 2015.

The move to shift all nursing students to private funding creates the opportunity to follow Lancashire Hospitals and offer loyalty incentives to newly qualified nurses

Despite the requirement for students to finance £9,000 fees plus living expenses through personal loans, the latest intake in September 2015 saw over 600 applicants to just 25 places.

Further places are now being offered in conjunction with Central Manchester and Bolton foundation trusts.

Karen Swindley, Lancashire’s director of workforce and education told the investigation she believed the substantial personal financial investment, combined with the fact the programme is focused on recruiting local trainees, meant the attrition rate from the course would be substantially lower than the 25 per cent plus seen nationally in recent years.

The scheme offers a key benefit and a potential advantage to other NHS organisations that struggle to recruit and retain nursing staff: Lancashire is offering to repay the equivalent of one year’s student loan debt in return for two years of continuous employment.

Such schemes are widespread in other areas of employment – particularly for professional qualifications.

The forthcoming national move to shift all nursing students to private funding now creates the opportunity for NHS organisations to follow Lancashire and offer meaningful incentives to newly qualified nurses in return for commitment and loyalty.

Using apprentices to grow your own workforce while providing one-on-one care

Evidence from individual trusts – and from the investigation survey – shows that the growing need to “special” patients for one-on-one care is a significant driver of nurse agency costs. Bedford Hospital Trust estimates, for example, that “specials” made up almost 2 per cent of its nursing staff fill rate in August 2014 – much of it at unpredictable times and therefore unrostered.

Individual providers have found that, while many of these patients may require qualified nursing support, a substantial and growing number are “specialed” primarily due to their dementia posing a fall risk.

A number of trusts – including Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals and Bedford – are developing strategies to use support workers on apprenticeship schemes to help care for such patients, while also receiving on-the-job training towards their professional progression.

Regional or conurbation-wide staffing banks

Work underway by NHS providers in large conurbations has identified significant variations in hourly pay rates between individual organisations’ nursing banks. Collaboration has begun to harmonise rates and merge individual banks into shared hubs that could both reduce costs to employers and increase the proportion of staffing gaps filled through an NHS bank rather than an external agency.

Recommendations

This report recommends that individual and regional NHS organisations assess the above examples of innovative practice for potential replication or adaptation locally.

It also recommends that NHS organisations and leaders:

1 Enhance pay and rewards to shortage specialties

While shortages in some clinical areas may be created or exacerbated by a failure to commission significant training places, in others – such as emergency medicine – the perceived unattractiveness of the role is also a significant factor.

Arguments by special interest groups such as unions that differential pay undermines collegial cooperation do not bear up to the reality of the current position: that medics and clinicians already work beside agency staff and locums paid at rates that are more than double standard NHS rates.

The long standing disparity in the earning potential between consultants working in specialties with private practice opportunities and those without further reinforces the point that pay disparity is already rife in the NHS.

With the average medical student graduating with around £25,000 of debt, the model developed in Lancashire for newly qualified nurses could perhaps be built upon and adapted to incentivise junior doctors to opt for shortage specialties.

Other more modest options being considered in parts of the country include contributions towards staff travel costs.

2 Improve transparency around bank use and rates

It is frequently said that the first step in addressing the NHS’s struggle with workforce planning is to establish a “single version of the truth”.

The same should be said of evaluation and measuring the success of efforts across the NHS to reduce reliance on temporary staff.

This requires clarity around the use and costs of bank staff in order to enable organisations to benchmark their progress and track the benefit of raising bank rates in order to attract staff away from agencies.

3 Promote the use of Allied Health Professionals

There are now myriad examples where AHPs including physiotherapists in hand trauma and orthopaedics, therapy radiographers in cancer pathways, consultant sonographers in obstetrics and diagnostic radiographers in musculoskeletal are both easing pressure on medical staff workload and improving patient experience. The NHS needs to hasten the adoption of these new roles and ways of working, and educate GPs and commissioners on their merits.

4 Offer flexible working

Part of stemming the flow of nurses leaving the NHS must involve offering staff more flexible working conditions. However, there is an urgent need to develop strategies to make flexible working patterns such as term-time-only contracts fit with the need for 24/7 healthcare and establish where trade-offs can and must be made.

Downloads

HSJ Workforce Investigation

PDF, Size 0.32 mb

HSJ investigation calls for improved pay to cut agency spending

NHS providers should enhance pay and rewards and offer flexible working hours to staff to tackle their rising spend on agency staff, HSJ’s Workforce Investigation has recommended.

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

The use of temporary clinical staff in the NHS – HSJ workforce investigation main report

3 Readers' comments