Essential insight into NHS matters in the North West of England. Contact me in confidence here.

The NHS in the North West stepped up and met the first challenge of the coronavirus pandemic.

Hospitals were reconfigured at unprecedented speed, with thousands of non-specialist staff rapidly trained to perform critical care roles they never would have imagined having to handle.

The region’s peak had been forecast to come around the start of May, but the lockdown and social distancing measures appear to have had a greater impact than expected. The number of people in hospital with covid-19 seems to have peaked at just short of 3,000 on around 13 April, with a peak in hospital deaths coming a few days later.

The numbers needing critical care were not as high as first feared, and hospitals were able to cope with the surge. Although it might feel awkward, the fact Manchester’s new Nightingale facility has so far remained largely empty is a symbol of this overall success.

Collateral damage

Attentions have already turned to the collateral damage caused by the virus — with increasing concerns over the sharp drop in emergency cases, such as strokes and heart attacks. I’ve been told of at least one case in which a patient died after delaying seeking emergency help.

Two-week cancer referrals — where GPs believe the case is urgent — are also down by more than 60 per cent in some areas, sparking fears that many cancers will flourish during the lockdown and be caught too late.

Urgent communications have been sent out to shift people back towards a more typical mindset when it comes to their health. In what must feel a very strange turn of events for a region like the North West, hospitals are having to encourage people to call 999, or go to accident and emergency, for help.

With many hospitals sitting half empty, and significant proportions of the workforce with lower than normal workloads, people’s minds are also turning to elective care, and beginning to tackle what promises to be a gargantuan new waiting list.

Strategy needed

While the initial challenge in responding to the virus was largely operational, the next challenge will be more strategic — to chart a course to try and get the majority of services up and running again.

Early discussions about how to do this have already started, but with some able to carry the virus without symptoms, leaders are struggling to see how they can create significant ‘clean’ areas, or hospitals, for normal care to be delivered without the virus seeping back in. Could the Nightingale still have a major role to play here, taking in large numbers of covid-19 patients and allowing the primary hospitals to be as clean as possible?

There will also be immense caution over the amount of NHS capacity that can be released, for fears of a second wave of covid cases as social distancing measures are eased. Bringing back electives, for example, would very quickly start to fill up critical care capacity, which is the key resource that needs protecting.

While the NHS has bought some breathing space to make these decisions, the risk will be that procrastination, risk aversion, local rivalries, and political challenges start to creep back in and slow the process. Cooperation, and clear lines of command, will be crucial.

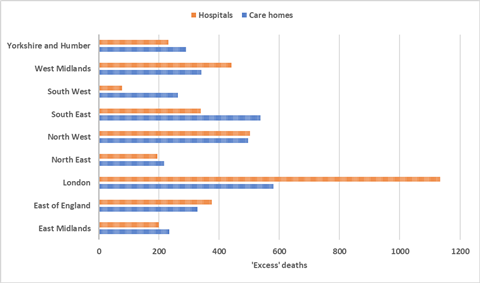

Supporting care homes like never before

Data from the Office for National Statistics — for all deaths from all causes up until 10 April — suggests the number of coronavirus deaths in care homes has been substantially underreported. Care homes in some parts of the North West have seen the number of deaths rise by several times, and by a greater degree than hospital deaths (see charts below).

Social care is used to being told it needs to support and protect the NHS. But in a few conversations I had last week, there was a notable recognition that support needs to go in the other direction.

This will need to come in the form of testing — to make sure care homes aren’t having to admit people with the virus — personal protective equipment, and possibly staffing as well, as is already happening in Northern Ireland.

Thousands of patients have been discharged more quickly than they normally would have been, and getting the NHS operating more normally will translate into increased demand for care packages. The existing social care workforce may be ill-equipped and too thinly spread to adequately support those patients.

There were a couple of developments last week which could help the sector in Greater Manchester, with the region devising a black alert system for care homes, and plans to launch a PPE factory which could enable the region to be less reliant on national supplies.

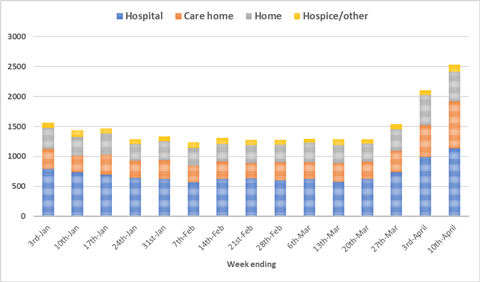

In week 15, there were 2,537 deaths from all causes in the North West — a potential ‘excess’ of more than 1,000…

North West defined as the NHS England region, so excludes North Cumbria

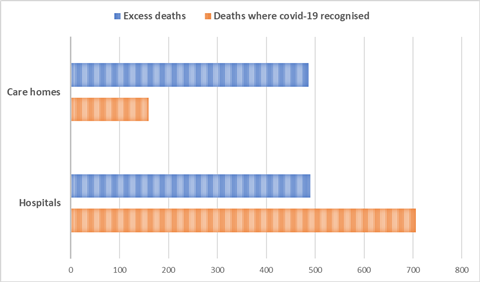

Excess hospital deaths were more than accounted for by covid-19, but the virus was recognised in a far lower proportion of care home deaths…

Excess deaths is the difference between the number of deaths in week 15 (to 10 April) and the weekly average to week 12.

Hospital and care sectors in the North West saw similar numbers of excess deaths in week 15…

Excess deaths defined as the difference between the number of deaths from all causes in week 15 (to 10 April) and the weekly average for the first 12 weeks of the year. In this chart, North Cumbria is included in the North West.

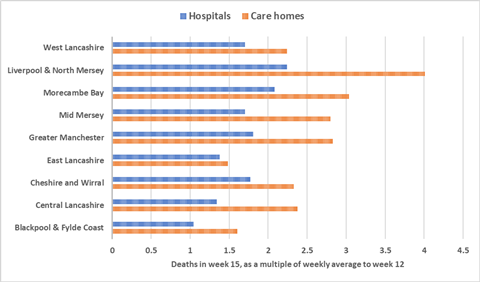

Liverpool had a four-fold rise in care home deaths

North by North West will focus on the region’s response to coronavirus until the pressures from the outbreak subside. Analysis of the progress of Greater Manchester’s devolution project will resume at that point.

Source

ONS data and information to HSJ

No comments yet