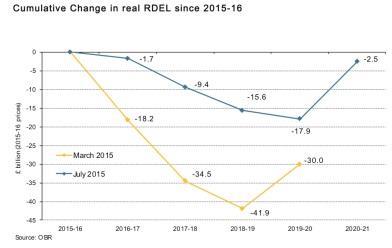

Osborne’s new plans get rid of the so called ‘roller coaster’ profile of public spending for the next few years, but although it’s a smoother ride, it’s still a very scary drop.

The chancellor’s summer Budget statement had headline announcements on welfare reform and the living wage. Beyond the headlines, for the health service the policy contours of the next five years are taking shape.

The NHS Five Year Forward View has a new name: the Stevens plan.

‘The policy contours of the next five years are taking shape’

In line with the Conservative Party’s manifesto, the chancellor committed the government to the “Stevens plan”. He confirmed that “the NHS will receive – in addition to the £2bn we’ve already provided this year – a further £8bn by 2020” with the service needing to find £22bn of efficiency savings. This is the fixed point for the NHS going into this autumn’s spending review.

The Stevens plan follows on from the Nicholson challenge of the last Parliament.

- Budget: Osborne sets deadline for future devo deals

- Ham: Make small improvements over time to meet the Stevens challenge

Balance the books

The Budget announcements highlight that while the name has changed, the government is looking to use some of the same tactics to balance the NHS books.

Pay restraint for NHS workers was a big part of the savings plan for the last coalition government – George Osborne is banking on more of the same. In the Budget on Wednesday, he announced that public sector pay awards would be limited to one per cent a year for the next four years.

The Budget poses four big questions for the NHS:

- Just how realistic is it to keep pay to 1 per cent a year for the next four years?

- If pay restraint can’t hold, can the NHS really deliver £22bn of efficiency?

- How will the annual increases rising to £8bn be phased in between now and 2020?

- What will happen to social care funding and what will be the knock-on impact of further cuts and cost pressures in the care sector?

More clarity will come in the spending review in the autumn, but at this point the signs are that the answer to all of these questions is pretty gloomy.

Pay restraint

On pay, over the last five years NHS employees’ real earnings have fallen by around half a per cent a year. But this was in a period when private sector earnings were also falling in real terms (and at a slightly faster rate of 1.77 per cent).

With the economy growing, over the next four years the government’s official economic forecasters, the Office for Budget Responsibility, expect average wages to increase.

The table below shows the forecasts for pay and inflation - average earnings start to sharply outpace public sector pay awards from the next financial year.

‘If pay restraint doesn’t hold, achieving the £22bn in efficiency savings looks really tough’

Inflation (CPI) starts to pick up in 2017-18 eroding the buying power of NHS wages.

There is obviously a very real risk that for all the government’s announcements on curbing agency and temporary staff spending, we will start to see problems with recruitment and retention and further pressure on temporary staff budgets.

If pay restraint doesn’t hold, achieving the £22bn in efficiency savings looks really tough.

The Treasury will be very reluctant to give any more to health and the messaging from government seems to be hardening.

The Budget explains why. The chancellor is committed to eliminating the annual deficit by 2019-20 and is planning a surplus of 0.5 per cent of GDP in 2020-21.

Don’t look down

His new plans get rid of the so called “roller coaster” profile of public spending for the next few years, but although it’s a smoother ride, it’s still a very scary drop.

The envelope for public sector day to day spending (RDEL in the jargon) is falling 3.1 per cent of GDP over this Parliament compared to a 3.3 per cent reduction in the last.

This means that in 2019-20 (the planned trough in public service funding) spending will be £120bn lower than at the peak in 2009-10.

‘The chancellor has left very little room for health to get much more’

This remains a truly massive contraction in spending: half done, half still to go.

Health is protected from these cuts and the chancellor has now added defence to his list of protected departments.

It leaves him with very little room for health to get much more, and the outlook for social care is bleak. It was notable that the chancellor said nothing about the timetable for implementing the Dilnot reforms and whether local government will get any help to meet the cost pressure which the living wage will add to social care, where so much of the workforce is very low paid.

Tough times

The budget fiscal forecasts chart also shows that while there is some scope for increased health funding in 2020-21, how that funding is phased in between now and the end of the decade will be critical.

The NHS desperately needs funding to be front loaded.

David Bennett said the 152 foundation trusts are projecting a deficit of £989m this year - a huge increase on the already unsustainable net deficit of £349m last year.

‘The NHS desperately needs funding to be front loaded’

Savings from the Carter review work and new models of care will all take time to materialise.

But the chancellor will want to keep additional funding in the early years to a minimum to spare other public services from even larger cuts.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimate that spending on public services which have not been ringfenced from cuts will need to be £19bn lower by 2019-20 – that’s a 13 per cent real terms reduction over four years.

The spending review this autumn will be tough - that, at least, is certain.

Anita Charlesworth is chief economist at the Health Foundation

1 Readers' comment