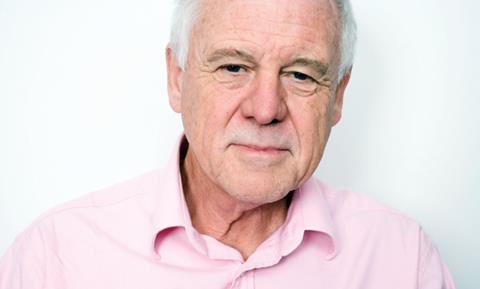

Despite the NHS’s stressful relationship with IT, Professor Michael Thick believes it can still be used to secure a sustainable future for the service, as he tells Daloni Carlisle

One of the most fraught areas of clinical leadership in recent years has been in the IT space. And yet some doctors keep coming back for more.

Professor Michael Thick is one of them. A former consultant transplant surgeon who advised the government on its organ transplant legislation and then chief clinical officer for NHS Connecting for Health, he is now in a senior leadership role at McKesson.

“I got into the world of clinical informatics, maths and computing while I was training as a clinician in Cambridge,” he says.

‘We were invited in too late to put a clinical face on something that was irretrievable’

He spent his first year after medical graduation as a biomechanical engineer earning the princely sum of £2,736 a year. “That made it quite clear that clinical medicine was a better option,” he jokes, but cemented his interest in how information and technology can be applied to the delivery of medical care.

As a consultant transplant surgeon, for example, he was involved in advising the government on new legislation to prevent the sale of donated organs for use in the private sector. He used computer modelling to demonstrate the draft legislation contained contradictory rules and could not work. “So they quietly redrafted it,” he says.

Late to the party

He went on to work for the Modernisation Agency, where he led the design team on Choose and Book. “Everybody hates me as a result, but we did deliver it on time and on budget.”

In 2006 came the role for which he is probably best known and that he describes as “probably the worst job I have ever done”: chief clinical officer for NHS Connecting for Health.

One of the acknowledged failings of the National Programme for IT was its lack of clinical engagement and only latterly, as the programme began to unravel, did the Department of Health bring a team of clinical leads onboard.

“We were invited in too late to put a clinical face on something that was irretrievable,” says Professor Thick.

“It was very, very difficult, in particular briefing ministers and trying to explain that if you are going to go down a highly contracted, obligatory route for implementation it will fail because no two organisations are the same and that if you try to impose what was in effect an American set of pathways into British systems it was going to be an extremely uneasy fit.”

Informing thinking

Most organisations decided not to involve clinicians before rolling out new systems, he says, “with the result that they would come in on Monday morning and find their entire way of working had changed. That did not go down well.”

He advised Connecting for Health about what clinicians wanted to see in a summary care record − the prime need being to have a view of a patient’s medication − but the answer came back that it was too hard.

“So they put in the summary care record that they had already designed without asking and again it did not go down well. GPs starting using it as the stick to stir up the consent debate.”

‘The dead hand was the prescription that you can only do things one way, the Connecting for Health way’

It was an acrimonious row and Professor Thick agrees that for the most part it was a red herring. “Most patients felt the same, except that unless you are rigorous and scrupulous about what you do take consent for in data terms you could go very badly wrong. At the end of the day, it is much simpler to ask; most people say yes.”

He and his co-leads did manage to make some important changes, among them the introduction of the “clinical five” into the 2008 information strategy review, which for the first time set out the clinical functionalities that all hospital IT should deliver. They still inform thinking today.

One-size fits none

In the meantime, he was working in a research role at Imperial College Hospital and the Royal Marsden developing systems that were led by clinical need. Among them was Coordinate My Care, an end of life care register where patients and clinicians record end of life care plans and share them with services as diverse as NHS 111, the ambulance service, hospices, nursing homes, GP out-of-hours services and A&E.

He could also see similar developments taking place across the NHS. “There were people with access to their records, there were effective electronic records. All the things that we think are important were happening,” he says. “But the dead hand was the prescription that you can only do things one way, the Connecting for Health way.”

Whereas the centrally imposed SCR has never really gained traction − and Professor Thick does not expect it to − CMC is now being rolled out across London.

So given that he knew the highly contracted, one-size-fits-all option was a bad one for the NHS, why take on this thankless CCO role and keep at it for four years?

His answer is straightforward: “It was a bit of a lose-lose situation and would have been a great deal worse if we had not been there to explain the whats and the whys.”

Heeding bad advice

When he joined McKesson as vice president for clinical strategy and governance in 2011 it raised a few eyebrows. Professor Thick is just one of a number of senior NHS doctors who now work in large software and technology companies such as Cerner, BT and CSC. Nearly all maintain either a part-time NHS clinical or research role alongside their corporate work.

Was this another example of the revolving door between the public sector and the private contractors?

‘How many hospitals have an all embracing secure wireless network? Very few. The whole penetration has not quite happened yet’

He argues not. “The appropriateness of the products depends very much on having a clear understanding of how the NHS operates and the people best placed to advise on that are the people who have done work in the NHS.” He is there to help the conversations that lead to good products.

At the heart of his role at McKesson is patient safety. He is responsible for making sure the clinicians who work for the company are who they say they are and that they maintain their registrations and that the company has robust clinical safety processes.

He also ensures that McKesson gets the right advice from the right level of clinician as it develops products and signs them off for clinical use − that it does the right testing to ensure patient safety.

“A prime example of where things went wrong at CFH was when we looked at the provenance of clinical advice of some of the iSoft products. We found that the ITU components had been signed off by district nurses just because they were clinicians.

“It is all too easy; just assume a clinical badge and get the wrong advice.”

A CSC spokesperson responded to this, saying: “Clearly our software products are tested rigorously and signed off by all appropriate authorities, including NHS Connecting for Health, before they’re released.

“We employ a great many medical experts from a wide range of disciplines and backgrounds, but naturally also seek and value clinical input from external stakeholders from all medical backgrounds. Our systems are built in collaboration with the NHS to ensure they meet the precise needs of the NHS.”

Making the links

The other part of his role is strategic. McKesson has acquired SystemC and LiqidLogic, bringing into its portfolio a wide range of tools to support health and social care and the integration of the two sectors.

‘There are enough junior doctors around who have grown up with technology and want to use it to do something better’

As the company works with a local health economy in north London to make the end-to-end social care and health record a reality, Professor Thick’s advice is clear: “It is very important to understand that the success of pathways and integration will not be solved by technology. It depends on teams understanding how they interact with each other and knowing what to do. Technology can facilitate that but it can’t drive it.”

Professor Thick is excited by direction of travel in the NHS. He, like others, argues that better use of technology and information is the only way to secure a sustainable future for the NHS. The necessary change can only come through supporting the innovation of entrepreneurs as they develop clinically meaningful systems that the NHS will readily adopt and spread.

But there is a long way to go. “How many hospitals have an all embracing secure wireless network? Very few. How many hospitals routinely use their electronic patient record in ward rounds? Very few. The whole penetration has not quite happened yet.

“But there are enough junior doctors around now who have grown up with technology and want to use it to do something better for the mentality to be correct. The technology is nearly correct. What we need to do now is link the technology to see the benefits we want of patient safety and patient outcomes.”

No comments yet