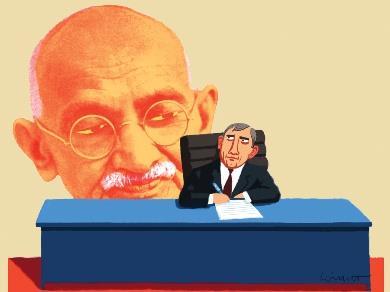

What can the NHS learn from Mahatma Gandhi’s key principles of truth, compassion and justice, asks Narinder Kapur

Gandhi’s autobiography was subtitled, Experiments with Truth. He saw himself not only as a trained lawyer, but also as a scientist, searching out truth.

In the NHS, one might expect that truth would be easy to find. However, there is often a lack of transparency, especially where errors have occurred. Patients may have difficulty finding out the truth about wrong-doings relating to their care. Staff who have genuinely raised concerns (‘whistleblowers’) may not be listened to or may be badly treated.

‘Gandhi once remarked: “It is not our patient who is dependent on us, but we who are dependent on him”’

As health secretary Jeremy Hunt recently stated, there seems to be an instinct in some parts of the NHS for institutional self-preservation to supersede the need to be honest and transparent about failings. Managers need to be open, apologetic and ready to learn from management failings, just as most clinicians are open, apologetic and ready to learn from failings in medical practice.

There is huge expenditure by trusts on legal proceedings involving compensation to patients or lawsuits brought by NHS staff who have been unfairly dismissed, but little transparency about such expenses, nor independent scrutiny at the time as to whether such expenses were justified or could have been avoided.

Those who are privileged enough to have power in the NHS should realise that with power comes responsibility, with responsibility come accountability, and with accountability comes transparency and a duty to be completely truthful.

Gandhi once remarked: “It is not our patient who is dependent on us, but we who are dependent on him. By serving him, we are not obliging him; rather, by giving us the privilege to serve him, he is obliging us.”

Gandhi showed compassion for his fellow human beings, especially those who were downtrodden (“untouchables”) or who suffered injustice. When Gandhi wrote about healthcare, he emphasised the importance of “service-before-self”. Sadly, in the NHS, compassion and tolerance have sometimes been subjugated to business priorities, management demands, or internal power politics.

Elusive justice

For Gandhi, means were more important than ends; unfortunately, some staff in the NHS have behaved as if the end justifies the means, even if this has compromised compassion and truth. Patient care would benefit if compassion and truth were part of an annual hippocratic oath for all NHS staff.

Ever since he was, simply because of the colour of his skin, thrown out of the first class carriage of a train in South Africa, Gandhi fought against injustice. Justice can be seen as a coalescence of truth and compassion. Both patients and staff have a right to justice.

We are all patients at some time in our lives and, when we are, we are often at our most vulnerable and least able to ensure that we receive justice. Yet justice may be elusive.

Professor John Hendy QC has provided a critical appraisal of the injustices in current NHS and legal procedures. As Lillenfeld and Byron have pointed out, there needs to be a recognition that the frailties of the human mind can lead to difficulties in discovering truth and implementing justice in judicial and semi-judicial settings. This affects patients/carers and also affects NHS staff who find themselves having to pursue litigation.

In a variety of legal settings, trusts can employ the most expensive lawyers, whereas patients or bereaved carers who have been wronged, and staff who believe that they have been unfairly disciplined, do not have similar resources. NHS disciplinary hearings may often be cases of the “police investigating the police”, ignoring the key concepts of independence of the panel from management, relevant expertise in the panel and plurality (more than one key decision-maker).

Moral leadership

Staff are sometimes offered huge sums of money in compromise settlements along with gagging clauses. Not only does this lead to injustice, it also holds back improvements in quality of patient care because unsatisfactory practices are not acknowledged and corrected, and money is unnecessarily diverted from clinical needs.

Finally, there is one other important lesson that Gandhi can impart to the NHS, that of leadership. As the eminent Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner noted, Gandhi was unique in showing individual courage (often entailing self-sacrifice), creating moral organisations and displaying moral leadership.

Be the change that you want to see in the world, was Gandhi’s simple but profound message. The more privileged the position one holds in the NHS, the greater the responsibility to set a shining example to others of courageous and principled leadership. Those who hold senior NHS positions should pay heed to Gandhi’s message.

Narinder Kapur is professor of Neuropsycholgy at University College London. References for this article are available at www.abetternhs.com

5 Readers' comments