The increase in the number of people with disabilities poses important questions for the role of the NHS and its broader contribution to society and health, write Kirsty Licence and Marion Bain

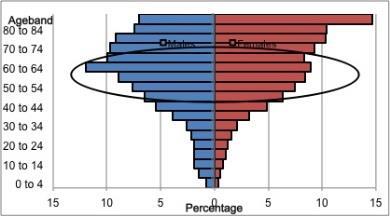

Demographic shifts alongside changes in retirement law mean that there is an increasing number of older people, and therefore more people with health conditions and disabilities, of working age. We clearly need to understand how this impacts on the NHS workforce, but beyond that there are important questions on the NHS’s role and its broader contribution to society and health.

‘The benefits of employment extend well beyond the individual’

Some work recently completed by NHS National Services Scotland provides some interesting, and challenging insights.

Nearly one in five of people in the UK report having a longstanding health condition or disability that limits their day to day activities to some extent. Of these, approximately half report that their health condition limited their activities “a lot”. And, although the prevalence of some conditions increases with age, some of the highest rates of illness are actually seen in people of current working age.

Having a disability relates directly to lower employment, the employment rate being less than half that of the population without any health problem (33 per cent versus 72 per cent).

Mental health conditions and physical disabilities are the most frequently reported problems among Scottish adults aged 16 to 64.

People with a learning disability have the highest risk of being economically inactive compared with people with other health problems – 85 per cent of adults with a learning disability in Scotland are in this category, compared with an overall rate of 63 per cent for all adults with any disabling condition.

Examining socio-economic differences shows that those living in deprived areas are doubly disadvantaged – Scottish data (Scottish Household Survey 2012) indicates the prevalence of disability is 36 per cent in the most deprived areas compared with 15 per cent in the least deprived.

In the most deprived areas 53 per cent of people with a disability areas are economically inactive compared with 18 per cent in the least deprived areas.

Benfits of employment

The benefits of working for individuals and their families is well evidenced. Benefits include increasing income, meeting psychosocial needs in a society where employment is the norm, meeting needs in relation to individual identity, social role and social status, and reducing socio-economic gradients in health and mortality.

Examining the impacts of employment for disabled people and those with health impairments, in particular mental health problems, musculoskeletal problems and cardio-respiratory conditions (these three accounting for two-thirds of sickness absence and work incapacity), work is associated with improved health and social outcomes, improved wellbeing and quality of life.

However, the benefits of employment extend well beyond the individual. For employers it increases the diversity of the workforce, provides visible representation of the consumer and customer base, and encourages innovation. Employee retention and morale can be increased, along with reductions in equality related litigation. By employing those with disabilities, health service organisations can visibly evidence their commitment to corporate social responsibility.

Society also benefits through reductions in ill health welfare benefits and backflow of tax and national insurance. And from a public health perspective there are contributions to the narrowing of socioeconomic gradient in health, benefits to children of disabled adults, and avoidance of intergenerational cycles of poverty, ill health and worklessness.

Return on investment

From a societal perspective, cost benefit analysis of supported employment consistently demonstrates benefits exceeding costs within 3-5 years from commencement. For example, a social return on investment evaluation of the benefits of project search, a targeted programme of employment training and support programme for people with learning disabilities, in North Lanarkshire Council 2013 calculated a total return of £276,659 across all stakeholders, for an investment of £69,910, giving a return of £3.96 for every pound invested.

‘A barrier to employment is lower levels of qualification in comparison with the general population’

There is limited information available about the employment of people with disabilities in the NHS. In England, 1 per cent of the NHS workforce declare a disability, in Scotland it is 0.5 per cent. Both are almost certainly underestimated, but it is not clear by how much.

If the employment of people with disabilities in the NHS is to be increased, it is important to understand what the challenges are.

A key barrier to employment is lower levels of qualification in comparison with the general population. In Scotland, 43 per cent of adults aged 16 and over with a disability have no formal qualifications, compared with 18 per cent of non-disabled adults. This may arise from disrupted education due to health problems, or exclusion from full engagement in education due to environmental barriers.

Lower levels of internet use may also limit access to job vacancies and online application processes, and reduce access to educational opportunities. The Scottish Household Survey reported that 38 per cent of adults with a health problem did not use the internet, compared with just 13 per cent of adults who reported no health problems.

Employer knowledge and perceptions around productivity, potential need for supervision, cost of adaptations and so on are also potential barriers to employment.

Doing more

What more could we be doing as a health service?

Approaches to improving employment opportunities for people with disability include visibly adopting and advocating for a social model of disability in which disability is seen not as individual impairments and limitations but as social barriers amenable to change.

Organisations can ensure that equality and diversity staff training supports a social model of disability and focuses on employee assets. More practically, engagement with partners in the voluntary sector and with further and higher education can create work experience, training and long term job opportunities.

Alongside this organisational and practice policies need to address the needs of different groups of jobseekers and employees, including new workplace entrants, older jobseekers who have been out of the workplace, and people in work when they acquire a health problem.

Strategies and specialist policies can also be used - for example, recruitment approaches that actively support employing people with disabilities by increasing access to job opportunities and application processes, and relying less on assessment through formal qualifications and interview. For employed staff, development programmes can be tailored to ensure employees with disabilities who have done less well academically at school.

‘The NHS workforce will increasingly need to attract and retain staff with disabilities’

And finally, the information available on employment of people with disabilities in the NHS needs to be improved – for assessing need, modelling future workforce and monitoring impact.

Alongside this, additional research should focus on ways of targeting economically inactive people for work opportunities, on modelling work to examine the impacts of changes in demography and health on patterns of disability, and on developing more effective interventions for promotion of mental wellbeing and prevention of mental ill health.

Welfare reforms are shifting support towards those in lower paid work while placing limits on entitlements for those not working at all. This places greater responsibilities on individuals to find work, but must surely also result in increased responsibility for employers, especially public sector employers, to ensure equality of access to work for those most disadvantaged.

The demographics tell us that the NHS workforce will increasingly need to attract and retain staff with disabilities. But, in addition, by improving its performance as an employer of people with disabilities, the NHS also has a vital opportunity to directly contribute to improving health and society.

Dr Kirsty Licence and Professor Marion Bain both work for NHS National Services Scotland

2 Readers' comments