The well-led framework, while designed to review foundation trusts and focus on development of board governance, reviews emerging themes that help trusts move from an organisational to a system leadership perspective. By Isobel Gowan and Michael West

While the public sector grapples with the emergence of sustainability and transformation plans and NHS boards find themselves facing an array of tough choices it is difficult to keep a focus on good governance.

Yet as organisations tackle change and new organisational forms emerge it is important for governance to be seen as an enabler rather than a necessary evil.

A focus on governance which has built from Cadbury through Nolan to the Healthy NHS Board and the subsequent well-led framework alongside the Care Quality Commission Well Led Domain (both recently subject to consultation following a heralded change in the Single Oversight Framework) the evidence we have collected from conducting well-led reviews provides an interesting snapshot.

We have worked with many NHS and other public sector organisations to support their boards in reviewing their governance over the last 10 years.

That privilege has allowed us to witness substantial good practice and a few areas of concern. The well-led framework was designed to review the governance of foundation trusts through the lens of the board.

Initially designed by Monitor, the well-led framework has become embedded though the approach to it has subtly changed. In the early years it was seen as an important measure which chairs and chief executives valued highly; now it is more of a mix.

It hasn’t quite become a tick box exercise but in some trusts it has felt like that – rather than a key component of good board practice and subsequent development.

Additionally, whilst the well-led framework focuses on board governance, issues often emerge about governance substructures below board level needing to be reviewed or aligned, particularly where in a trust the detail of issues (for example risk management) is handled.

We have been able to collect and collate data for 22 trusts who have commissioned a well-led review. This data set is unique and valuable, providing as it does a rich picture of how foundation board members see themselves, their board and their organisations.

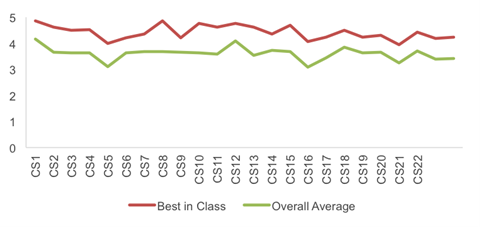

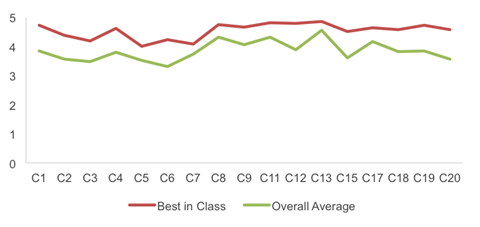

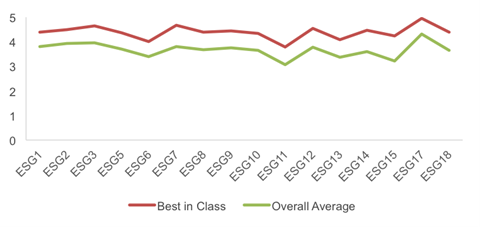

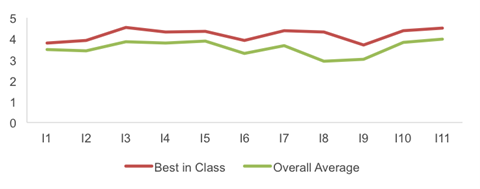

We explore below key emergent themes in each of the four well-led domains. These are illustrated graphically from the surveys we use as part of our well-led reviews: each data point represents the overall averaged opinion of all board members, and so is essentially a summary of a wider range of considerations.

Strategy and planning

Increasingly our reviews find that boards know that it is vital to hold on to their own organisational strategy but they find it hard to get time to do so. Often strategic planning is put aside for operational planning and performance monitoring.

Boards are not only grappling with what it means to be a foundation trust today, they are also endeavouring to work out how their strategy fits with those of partner organisations, locally and regionally.

We have found that quality assurance is still more of a focus than quality improvement –though high performing trusts are addressing this.

We are finding that board members, especially non-executive directors, are not only feeling frustrated at what feels like a curtailment of their powers but a sense that it is hard to provide sound strategic leadership to staff in such an ambiguous environment.

There are two particular aspects of this domain to note: first the lack of an overarching people strategy in a number of trusts to complement the organisational or system strategy (CS16 in graph below) and second what many boards regard as insufficient involvement of patients, carers and communities in developing strategy (CS5).

Given the critical importance of both of these issues, this is an area where boards will wish to pay more attention.

Context and strategy (1 is low and 5 is high)

Capability and culture

In high performing trusts we notice that detailed attention has been paid to the skills required for a successful board; that there is an explicit recognition that board behaviour sets a tone for organisational culture; and that this is borne out in how board members work with each other and with staff.

A number of trusts we reviewed had done in depth work on their organisational culture led by the board.

We have found that quality assurance is still more of a focus than quality improvement –though high performing trusts are addressing this.

Interestingly, where quality sub committees have a broader agenda - for example quality, performance and safety or quality and finance - NEDs in particular tell us it is difficult to keep their focus on quality.

Boards are not only grappling with what it means to be a foundation trust today, they are also endeavouring to work out how their strategy fits with those of partner organisations, locally and regionally.

Whilst we would accept that having additional sub committees can mean extra work it is vital that sub committees have a realistic agenda where members feel that they have a good chance of getting a grip and really understanding the issues.

Within this domain, learning and development strategies can be hard to discern. As highlighted above there is an increasing need to focus on workforce challenges and workforce planning so some boards have created a new sub committee to focus more strategically on the people aspects of their business.

Other areas where board members are less confident in their own organisations include:

Perhaps not surprising given the pressure on boards in relation to formal governance through attendance at meetings, we also note consistent feedback and a lower score in relation to board visibility (C15).

Culture

Processes and structures

Reviewing board and sub committee papers as part of a well-led review provides a snapshot of both efficiency and decision making. Looking at current papers and those from a year ago is a useful way of discerning the attention paid to board process and the expertise of the company secretary.

Often now it appears that boards are not making decisions but are presented with a vast array of data to provide them with assurance.

More critically for trusts is the volume of information presented to boards and sub committees and the exhortation that the board must have sight of and sign off an increasing number of submissions-this has the risk of board members not being able to discern the critical issues/hotspots in the services and not being able to give sufficient time and scrutiny to the delivery of performance. The desire to increase assurance runs the risk of reducing it.

Good boards have invested in systems to deliver business intelligence and predictive analysis. So often boards are looking back rather than forward.

Engagement is a critical issue in this domain - with staff, patients, governors and key stakeholders. Indeed in our experience the responsiveness of stakeholders to a request to complete a well led survey is often a simple yet accurate indicator to the nature of local working relationships.

What is striking - given the current push for system leadership are board members’ lower scores in relation to ESG 15 “How would you assess the performance of the board in engaging local government and social care providers?” and ESG 9-11 which relate to engagement with governors and members. These are clearly areas for improvement.

Engagement and system governance

Measurement

Good boards have invested in systems to deliver business intelligence and predictive analysis. So often boards are looking back rather than forward.

It is of concern to see boards and NHS staff grappling with out of date and cumbersome IT and even manual systems in order to generate credible data for boards to be appropriately assured.

Of all the domains assessed and analysed as part of a well-led review this is the area with the greatest disparity. Some trusts have excellent systems of data intelligence with scorecards and dashboards which greatly assist boards to be assured.

Others however are grappling with long out of date systems and technologies which are both barriers to staff in delivering care efficiently also to board members looking for sound data and indeed predictive data.

Intelligence

Conclusion

In its current form the well-led review has been a useful tool for foundation trusts, particularly where they have used it as an integral part of the board development journey.

Nonetheless in reviewing the themes emerging from our work we note that there are areas where boards lack confidence – including many which will be essential in moving from an organisational to a system leadership perspective.

As organisations tackle change and new organisational forms emerge it is important for governance to be seen as an enabler rather than a necessary evil.

Finally, we suggest what boards can do to focus on the most common concerns

- People and learning strategies: ensure there is a non-executive working alongside the HR/OD director to ensure there is consistent board focus on this area with a dedicated sub committee and underpinning strategies which align with the trust strategy

- Getting committee structures right: ensure the director of corporate affairs/company secretary is enabled to establish regular reviews not only of board sub committees but also the governance structures below that.

- Streamlining information and keeping the board strategic: chairs should ensure that board meetings do not repeat the discussions already held at sub committees and in operational meetings. Trusts should invest in analytical capacity to ensure that boards and trust leaders receive predictive and current information not just data about what has already happened.

Isobel Gowan is director and Michael West is senior consultant at GE Healthcare Finnamore.

No comments yet