How can the NHS tackle impotent leaders and expel underperformers, asks Michelle Russell

As Sir Dan Moynihan’s example shows, when we’re talking about turnarounds in schools and hospitals, the parallels in approach and philosophy - everyone deserves access to good education and healthcare - are compelling.

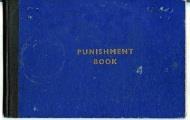

One of the keys to Sir Dan’s turnarounds is that underperforming teachers have been required to leave - a feat perceived by most as nearly impossible in the NHS.

I was with the NHS Leadership Academy in Leeds last week with a cohort of senior nurses and midwives - seasoned, pragmatic, inspiring women and men from across the NHS who, above all else, think about, talk about and care about the patient. I heard a story after story of how seemingly impossible it is to remove underperformers, especially those who behave badly.

At best, leaders seek to ringfence and neutralise toxicity. Sometimes HR supports the leader. More often they unwittingly collude, perpetuating the norm that it’s almost impossible to deal decisively with bad performance or behaviour.

It’s as if a sort of learned helplessness has taken hold. This pervasive sense of powerless is surprising in the post-Francis report era, where most trusts are focusing on leadership and values.

‘For every 10 seemingly impotent leaders, one does speak up with their story of staring down the orthodoxy’

For every 10 seemingly impotent leaders, one does speak up with their story of staring down the orthodoxy. They tell of their journey to “we’re not putting up with not ‘good enough’ anymore”.

The success stories show that leaders must model positive behaviours and hold each other to account, or values simply remain words on a page.

They describe what values such as compassion, safety, and excellence look like in practice.

They invest in coaching for managers, and they embed values and behaviours into everything they do: how they attract and hire; how they induct new employees; how they hold up and reward good behaviours; and how they manage those whose values - expressed as behaviours - are not aligned to the organisation’s.

‘It is little wonder it is almost impossible to dismiss staff who don’t or won’t embrace organisational values’

They do so without apology and so the impossible becomes possible - not easy, but possible. And it’s a little easier the next time too. After a while, the written standard becomes the cultural norm, which in turn allows the organisation to raise the bar from good to excellent. People engage and sign up emotionally - an upward spiral of sorts has begun.

Without values expressed in behavioural terms, embedded in expectation setting and factored into employee appraisals, it is little wonder it is almost impossible to dismiss staff who don’t or won’t embrace organisational values.

A final note is the federation’s use of chain schools to drive efficiencies. Within the NHS, where competition has been encouraged and local autonomy has become sacrosanct, fragmentation is the norm. Hospital chains are rare. However, Sir David Dalton is looking at getting trusts to group together into “chains”.

Our experience tells us two things: form should follow function and, at the heart of a successful healthcare group must be a set of healthy relationships between collaborating parties - just as in Moynihan’s academy experience.

Michelle Russell is director at GE Healthcare Finnamore

Topics

Lessons from a school master

Sir Dan Moynihan is a maestro of turning around failing schools

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

How Sir Dan Moynihan's stance on bad behaviour could work in the NHS

- 3

No comments yet