Anita Charlesworth discusses the dilemma facing the government: improving the quality of the health service through a rise in healthcare spend or increasing the low level of taxes

In March, Theresa May announced that there would be a multiyear funding settlement for the health service this year. Speculation is rife about whether she might make an announcement before the 5 July celebrations for the NHS’s 70th anniversary.

That would clearly have political appeal. However, a new study from the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Health Foundation shines a light on why the government is apparently finding it hard to settle on a number.

On the horns of a political dilemma

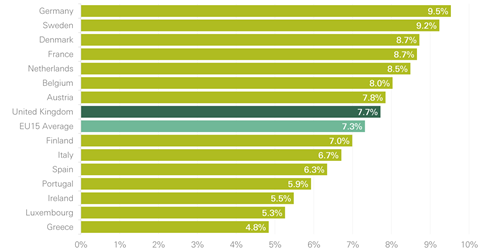

The problem is encapsulated in two charts. The first shows that compared to the EU25, the UK devoted an average share of GDP to health spending from public funds or where citizens are required to contribute. On this internationally consistent measure, the UK spends 7.7 per cent of GDP (it’s a bit different to how Treasury categorises health spending which gives you 7.3 per cent).

The trouble is that spending growth has lagged behind demand and cost pressures for eight years now; no one who looks at the evidence can see how that can continue without quality and access to care suffering further.

To get to the EU15 level of healthcare spending, funding grew by an average of 4 per cent a year over the first 60 years of the NHS; before the current round of austerity. IFS and Health Foundation research suggests that for the next 15 years the annual increases in NHS funding need to return to the pre-austerity average increases of 4 per cent a year in real terms if we are to see any improvement.

The problem for the government is that while this makes sense for the NHS, it’s a serious public finance headache. In the past, we have effectively paid for extra health spending by cutting other things – we spend 6 per cent of GDP less today on defence, debt interest and housing than we did 40 years ago. Health has gobbled that up. The result is an element of “have cake and eat it” for politicians and the public; NHS spending rose (very popular), but the tax burden didn’t (also very popular).

Those days are gone, it is extremely hard to see how we could repeat that trick over the next 15 years. There is nothing obvious to cut which would yield anywhere near enough money for the NHS. This leaves us with a conundrum; can we sustain a European standard of care in the NHS on current UK levels of tax?

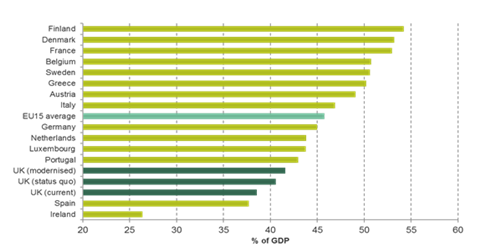

As the second chart shows, we are a comparatively low tax economy. Our analysis of health spending pressures would see health and social care together take 3 per cent more of GDP in 15 years’ time. If the money for extra NHS and care spending comes from tax – as surely it must – we face a big tax rise by UK standards. But while big by UK standards, it would still leave us a low tax economy by EU standards; 13th in the EU15 tax league.

The government’s dilemma is which should give; the quality of the health service or the level of tax? We are rapidly heading towards the point where we can’t duck this choice. Government, understandably, doesn’t find this easy to resolve.

Even more hospitals or can we finally transform services?

Big challenges aren’t the unique preserve of politicians. Over the next 15 years, the UK population aged 65 and over is due to rise by 4.4 million. For the NHS that in itself would be hard to manage; the healthcare costs of someone over 65 are about three times as much as someone under 65. But the pressure of an ageing population is hugely exacerbated by the very rapid rise in chronic conditions, particularly multimorbidity.

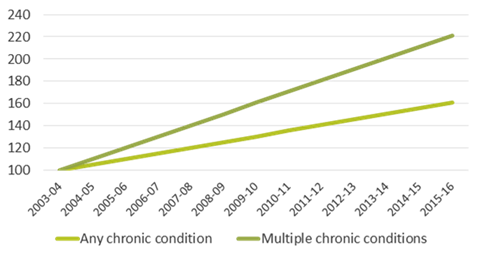

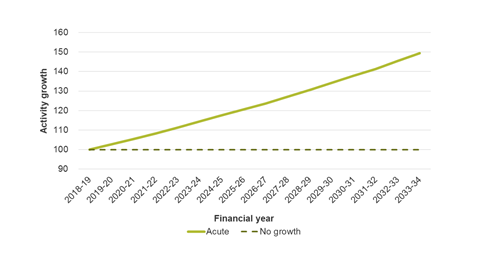

The third chart shows that the proportion of people over 65 being admitted to hospital with multiple chronic conditions has more than doubled since 2003-04. That rise in multimorbidity translates into a 50 per cent increase in the amount of acute activity, unless we radically change the way care is delivered (chart 4).

Talk of closing hospital beds in the medium term looks wildly unrealistic. The task will be to limit the growth in bed capacity.

For that we need to make a reality of the new models of care set out in the NHS Five Year Forward View. The scale of change required can’t be underestimated. It will need a balance of determination and realism.

Over the last 20 years, funding growth and workforce has been skewed towards acute care. Shifting the balance will need capital investment.

It also needs real clarity about what new, fit-for-purpose services in primary and community health care will look like. Crucially, we need a very well executed plan of action to scale those new services across the country. But most of all it needs the right workforce, and on that we are going backwards not forwards; GP numbers fell last year.

Change is always much easier to promise than it is to deliver. The temptation for both politicians and the NHS is inevitably to back away from these big challenges and lower sights to managing the day to day. Although that temptation is understandable, it would be wrong.

2 Readers' comments