The announcement about the NHS funding settlement can be interpreted in two ways, says Ben Gershlick

In 1887, Friedrich Nietzsche wrote “there are no facts, only interpretations”. Back then we didn’t have NHS funding announcements – the NHS was still 60 years away.

But fast forward 180 years, it still rings true. You will have heard some very different numbers over the weekend depending on which newspaper you read, which radio station you listen to, who you follow on Twitter – even what time of day you woke up.

There has been a glut of announcements and analysis about health funding as Jeremy Hunt and others – perhaps eager to set an example by working weekends to provide a seven day a week health policy service – set out a funding settlement for the NHS.

Luckily, there are also some facts. The announcement is that NHS England’s main budget will be £20.5bn larger in five years’ time than it is now (just less than £400m a week), growing at 3.4 per cent a year on average.

NHS England is the organisation in charge of distributing money to the NHS and so its current budget is £115bn of the Department of Health and Social Care’s total budget of £129bn. (This assumes the additional £800m cost of the new Agenda for Change pay deal is added on top of the DHSC’s current budget, rather than found from elsewhere in it.)

Some of the other numbers can be dismissed quite quickly. £600m per week is not a very helpful number. It is in “cash terms”, which means it can’t be compared with current spending as it is essentially expressed in 2023-24 prices, which is obviously not meaningful as it is currently in 2018.

Another red herring is the idea of a “Brexit dividend”. There have been good and thorough analyses of why, but in short, the UK never paid this much money to the EU. The payments it does make will continue for now, and the government’s official forecasters – the Office Budget of Responsibility – and others have made clear that the cost of Brexit will outweigh the benefit of not making these payments.

It is worth noting that this money is “frontloaded” – in the first two years, the budget grows by 3.6 per cent, and then by lower amounts. There is also £1.25bn in cash terms a year extra (on top of this money) as a result of pension revaluation – although this is also a cost for the NHS so it’s not really an increase in funding, and may change depending on what the pension costs end up being.

In the spirit of Nietzsche, there are two interpretations of these facts.

A generous interpretation

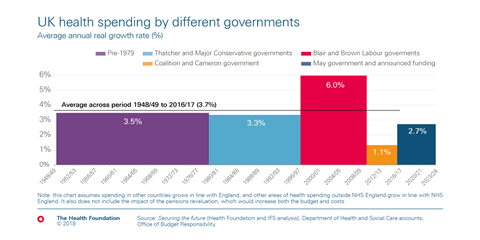

The first interpretation is that this is the end of a period of historically low funding for the NHS since the financial crisis – a “change of gear” according to Simon Stevens, who leads NHS England. NHS funding has risen by just 1.5 per cent over the last eight years – the lowest period of growth in the NHS’s history.

The new announcement of 3.4 per cent a year growth for NHS England should mean the budget as a whole grows by at least double this low rate (NHS England accounts for about 90 per cent of the total health budget).

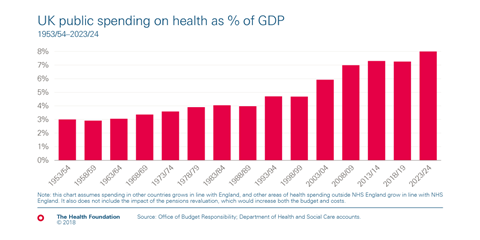

With national income expected to only grow by 1.4 per cent a year over the period this will mean that health spending as a percentage of GDP could grow to around 8 per cent – a historic high

On top of this, as set out in our recent report Securing the future, these increases should allow spending to keep up with the pressures that come with a growing, ageing, and increasingly multimorbid population – as well as cost pressures that come from things like medicines getting more expensive and pay growth.

With other areas of public spending still facing cuts, it is impressive that the NHS has made the case for increased spending in the current fiscal climate.

With national income (GDP) expected to only grow by 1.4 per cent a year over the period this will also mean that health spending as a percentage of GDP could grow to around 8 per cent – a historic high. This could be a little higher or lower depending on parts of the budget which haven’t been announced yet, as well as choices made by Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

A system creaking under pressure

The second interpretation is less positive.

The result of eight years of remarkably low growth in health spending is that providers are in deficit to the tune of £960m. (This would likely be higher if not for one-off funding increases and accountancy changes meaning that the finances of NHS providers are even more precarious than it seems.)

Likewise, staff engagement and retention has fallen, waiting times have deteriorated, and there is a backlog of maintenance required to the NHS’s buildings.

Funding between 2015-16 and 2023-24 is likely to be about a percentage point below the historical average of 3.7 per cent

Under this interpretation, the money goes into a system creaking under pressure – and these cracks will need to be papered over. While the additional funding over the next five years may be enough to keep up with spending pressures, the funding over the last eight certainly hasn’t been.

Funding between 2015-16 and 2023-24 is likely to be about a percentage point below the historical average of 3.7 per cent. This again depends on decisions on spending which have not been made yet, in particular around the rest of the DHSC’s budget, and spending in the rest of the UK.

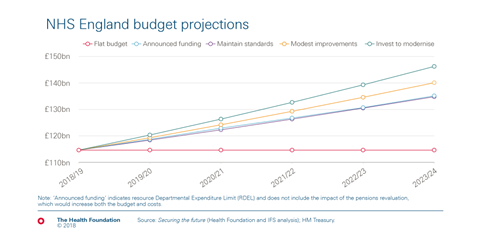

Similarly, our analysis in Securing the future shows that this money is nowhere near enough to modernise the NHS and make serious investment in areas like mental health treatment and spending on buildings and equipment. This would require about 4 per cent a year over the next 15 years, and would likely need frontloaded investment of around 5 per cent a year over the next five years.

Does that settle it?

The temptation is to think that, at least for now, some really tough conversations have been headed off. But the announcement is only the start.

For one, we still do not know what the settlement will be for areas outside of NHS England. If this increase does not include increased spending in other important areas of the DHSC’s budget – for example much of public health and training of staff, as well as social care – then it will fail to maintain current standards of care.

The “change of gear” Simon Stevens refers to may well be into reverse. If the rest of the budget does not grow in line with NHS England’s budget, then the increase may be around 3 per cent – below the level required to keep up with spending pressures.

We might not have these issues resolved until the Spending Review next year, which means the pressures will not be easing off anytime soon.

If the rest of the budget does not grow in line with NHS England’s budget, then the increase may be around 3 per cent – below the level required to keep up with spending pressures

On top of this, money is only as good as what it is spent on. This new money does not allow the NHS to run Supermarket Sweep-style through the aisles of the health policy supermarket.

At best, it should help stem some of the deterioration of the last eight years in areas like waiting times, staff engagement, and NHS provider deficits. The Treasury will be expecting these improvements, which means there will be no shortage of tricky conversations around the “10 year plan” the NHS has been tasked to come up with.

And so, for what was advertised as a funding settlement, there’s an awful lot yet to be settled. While we at last have some facts and some certainty, two interpretations remain true: it is welcome relief after the last eight years, but a missed opportunity to modernise the NHS.

No comments yet