Steve Ford and Claire Read look at the changes at the top brought about by the Francis, Keogh and Berwick reports on failings in the NHS

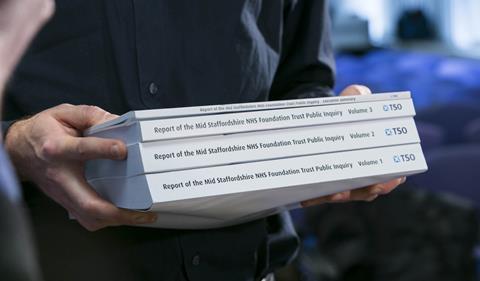

There have been a number of high profile reports in 2013 about quality in the NHS; Francis, Keogh and Berwick have all shined a light on care failings and made suggestions for change.

This has led to an increasing focus on the role played by non‑executive directors at healthcare trusts. According to Carmel Gibbons, partner and head of health practice at executive search firm Odgers Berndtson, “never before has so much weight been placed on the personal traits and behaviours of non-executive board members”.

‘Francis has significantly shifted the system’s focus from finance to quality’

“Chairs and non-executive directors are becoming increasingly aware of the responsibilities they hold around assurance,” she argues, “and this is impacting on the types of individuals who now put themselves forward for board roles in the NHS.”

It is an assertion borne out by a HSJ focus group of 18 trust chairs, carried out over the autumn. “The expectations are rightly very high,” said one member. “Some issues present particular difficulties − for example, getting the balance right between strategic leadership and operational oversight.”

When HSJ surveyed 60 provider trust chairs in March, post-publication of the Francis report, 30 per cent said they expected their boards to focus on quality to an increasing extent. When we spoke to the focus group chairs over the autumn, 10 members said they were now concentrating more on quality and two on operational issues. The remainder said there had been no change in the way they were operating.

One said: “Francis has significantly shifted the system’s focus from finance to quality.” However, another noted an example where he had spoken to a newly qualified consultant about the Francis report whose views, he said, “didn’t go beyond the focus on basic nursing standards”.

Revealingly, 15 members of our focus group - which was run in association with Odgers Berndtson − said they had felt it necessary to challenge an executive on issues around poor performance following the reports published by Robert Francis QC, NHS England medical director Sir Bruce Keogh and US patient safety expert Professor Don Berwick. Two said they had done so on one occasion and 13 more than once.

Confident culture

But this potential concern was countered by the positive fact that all of the focus group felt very confident that their board’s culture allowed them to challenge executives when necessary. Interestingly, half of the chairs said the make-up of their board had changed either significantly or slightly since the publication of the Francis report in February.

‘Non‑executive board members want to get about in their organisations and ‘kick the tyres”

Our focus group members also told us that they are engaging with the front line. Fifteen told us they visit clinical areas once a week, and the remainder of the group reported once a month. Ms Gibbons suggests this reflects that “non‑executive board members want to get about in their organisations and ‘kick the tyres’ to satisfy themselves that what they read on paper is replicated on the shop floor”.

That could lead to time challenges, as well as challenges when it comes to specific clinical knowledge. Ms Gibbons argues the time now needed to be an effective non-executive will “prove prohibitive for many, particularly those still in full‑time employment”.

She also suggests trusts will increasingly have to look to include board members with a clinical background: “Having a non-executive director who can offer challenge on a clinical level and champion patient welfare is now seen as vital.”

Positively, all but two of the focus group believed their access to information had improved, in terms of transparency and availability, since the publication of the Francis report.

However, the group suggested there was still a way to go regarding internal and external communication. None considered communication across their organisation or with the general public to be as good as it could be, and most said there was room for significant improvement in both areas.

‘Our focus group was divided on criminal sanctions − half were in favour, and half against’

Our focus group members were also quizzed on the pressures facing their organisations. Fifteen of our 18-strong group said they thought their trust was understaffed - either slightly or significantly − tying in with figures reported in October by HSJ that show many trusts are attempting to recruit more nurses at present. The other three chairs judged their workforce to be “about right” but none felt they had too many staff.

Regarding finances, 11 of the focus group considered their organisation to be “a bit” under-resourced, but four warned they were “dangerously” under-resourced. More than half of the group thought they were likely to breach accident and emergency performance targets this winter due to a lack of sufficient resources.

As well as looking at current pressure, we asked our focus group about some of the new policies stemming from Francis, Keogh and Berwick − most notably the duty of candour. Seven of our chairs supported the Francis report’s call for a statutory duty of candour to apply to all individual NHS staff, though the idea was rejected by the Berwick report and subsequently the government in its response.

Criminal penalties

However, the Berwick report recommend new criminal penalties be introduced for NHS leaders who had acted “wilfully recklessly or with a ‘couldn’t care less’ attitude and whose behaviour causes avoidable death or serious harm’”.

News that clinicians and managers found guilty of “wilful neglect” of patients could face up to five years in prison under a new criminal offence was the early story given to the national press by the government, ahead of its official response to Francis and the others. On this, our focus group was divided − half were in favour, and half against.

‘The variability of experience among governors and their wide range of backgrounds make it challenging to ensure real joint working’

There was a similar split on the Care Quality Commission’s new inspection regime, being led by chief inspector of hospitals Professor Sir Mike Richards. Four chairs thought the model would have a negligible impact on quality of care, compared with five who thought it would have significant improvements. The remainder were either unsure or believed it would lead to small improvements.

There was also uncertainty over the effectiveness of other new structures resulting from the government’s reforms. No one in the HSJ focus group thought the council of governors model for ensuring good accountability and governance in foundation trusts was fulfilling its role as well as intended. The focus group rated the model an average of five out of 10.

One chair said: “The variability of experience among governors and their wide range of backgrounds make it challenging to ensure the correct level of communication and real joint working.” Another described the role of governors as a “major issue”.

The group was slightly more positive when asked to rate how their trusts’ relationships with CCGs were developing. This could be affected by the fact that few chairs thought CCGs were the main source of pressure to change at present. Despite the intended local drive from CCGs and the creation of NHS England as a counterpart of the Department of Health, 10 out of the 18 chairs judged the most pressure to change as coming from government.

One member said they were looking at allowing CCGs to attend trust board meetings to “share thinking about our performance effect on their commissioning intentions”.

After all the reports, who’s in charge?

Looking at changes at the top of the NHS following Francis, Keogh and Berwick

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

After all the reports, who’s in charge?

- 2

2 Readers' comments