The King’s Fund’s Hugh Alderwick and Chris Ham learn the lessons from overseas on integrating care for local populations

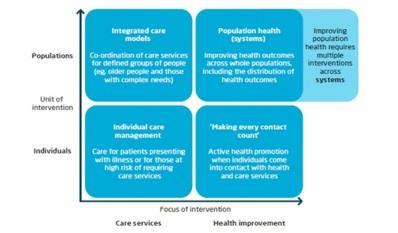

Integrated care has become part of everyone’s agenda in the NHS. Overcoming the fragmentation of services, both within the NHS and between health and social care, is commonly articulated as a key aim by policymakers and local leaders.

The better care fund, integration pioneers and the care models described in the NHS Five Year Forward View - and its resulting vanguard programme - are all examples of integrated care in the spotlight.

‘We need to think differently about what integrated care is trying to achieve and where it is heading’

Some areas are making progress in coordinating care services for older people and those with complex needs who are already or at high risk of becoming ill.

Although this is the right place to start, these efforts rarely extend into a concern for the broader health of local populations and the impact of the wider determinants of health.

Rather than seeing the argument for integrated care as coming to an end, we need to think differently about what integrated care is trying to achieve and where it is heading.

This means thinking about integrated care as part of a broader shift away from fragmentation and towards an approach focused on improving population health across local systems.

This reflects what we already know: that health and care services on their own can only do so much to improve population health, which is influenced by a wide range of social, economic and environmental factors.

- The independent sector can help the NHS invest in new care models

- Mapped: The new care model ‘vanguard’ sites

- New care models explained: How the NHS can successfully integrate care

Take a Bow

Elements of this type of approach are already happening in parts of the country.

A well known example is the Bromley by Bow centre in east London, whose work is based on collaboration across services and sectors to improve the health and wellbeing of vulnerable young people, adults and families across the community it serves.

Elsewhere, initiatives have been developed that recognise the links between people’s health and their living environments, as well as the impacts of poverty, deprivation and lifestyle.

‘In many parts of the country, the paths of integrated care and public health have rarely crossed’

One example is the Healthy Homes Programme in Liverpool, which has achieved positive results, such as reductions in the number of winter deaths and financial savings for the NHS.

Yet the challenge for local areas remains how to build on and join up these often small scale initiatives to create more systemic approaches to improving population health. In many parts of the country, the paths of integrated care and public health have rarely crossed.

Nuka options

Lessons can be learned from other parts of the world, where organisations and systems are beginning to make these connections as part of a single approach. They go beyond the integration of care services for patients to explore how they can improve the broader health of the populations they serve.

One example is the Nuka System of Care in south central Alaska, which serves a population of around 60,000 people.

Nuka combines integrated health and social care services with a broader approach to improving family and community wellbeing across the population - for example, through initiatives aimed at tackling domestic violence, abuse and neglect through education, training and community engagement.

The Native and American Indian population in Alaska are seen as “customer owners” of the system and play a central role in designing services.

‘The Native and American Indian population in Alaska are seen as “customer owners”’

Since it was established in the late 1990s, Nuka has achieved reductions in hospital activity, high performance in the US healthcare effectiveness data and information set and high levels of user satisfaction.

Teutonic shift

Another example is health consultant Gesundes Kinzigtal in south west Germany - a joint venture between a network of local GPs and healthcare management company OptiMedis.

Since 2005, it has been responsible for organising care and improving the health of about half of the 71,000 population in the region.

‘Gesundes Kinzigtal collaborates with traditional health and care providers, as well as with gyms and sports clubs’

Gesundes Kinzigtal collaborates with traditional health and care providers, as well as a range of community groups such as gyms, sports clubs, education centres and local government agencies.

It runs health promotion programmes in schools, workplaces and for unemployed people, and a range of targeted care management and prevention programmes for particular high risk groups.

Evaluation shows that Gesundes Kinzigtal’s approach is improving health outcomes, as well as slowing rises in healthcare costs.

American model

A third example is Kaiser Permanente in the US, whose longstanding efforts to integrate health and care services are likely to be known to many.

Key features of its approach include its model of multispecialty medical practice, extensive use of technology and population data, and a focus on prevention and disease management for different population segments.

Kaiser Permanente has also been involved in efforts to improve the “total health” of the wider communities it serves for several years. This includes supporting food stores in deprived areas to stock fruit and vegetables, working with schools and food banks to offer nutritional food, and promoting healthy living in a variety of other ways. It also works with local government agencies through a range of initiatives to ensure that health is considered in local plans and policies.

Common ground

In particular, the approaches of emerging population health systems such as these can be described across three broad levels: macro, meso and micro.

At a macro level, they involve organisations working together to improve health outcomes for defined population groups, as well as targeting specific interventions in the most deprived parts of their populations. This is often supported by:

- population level data to understand need and track health outcomes;

- population based budgets to align financial incentives with improving population health;

- community involvement in managing their health and designing local services; and

- involvement from a range of partners and services that have an impact on population health.

At a meso level, they develop different strategies to improve the health of different parts of the populations they serve (like older people with complex needs, or children), depending on people’s need and risks to their health.

This is often supported by population segmentation and risk stratification to identify the needs of different groups within the population, targeted strategies for improving the health of different population segments, and the development of “systems within systems” with relevant organisations, services and stakeholders to focus on different aspects of population health.

At a micro level, they deliver a range of interventions aimed at improving the health of individuals within their populations.

This is often supported by:

- integrated health records to coordinate people’s care services;

- scaled up primary care systems that provide access to a wide range of services and coordinate effectively with other services; and

- close working across organisations and systems to offer a wide range of interventions. Professionals also work closely with individuals to understand the outcomes that matter to them and to empower people to manage their own health.

Home run

Achieving this kind of approach in England will require action and alignment across a number of different levels, from central government and national bodies to local communities and individuals.

‘Achieving these approaches in England will require action and alignment across various different levels’

For public services, this means “joining up the dots” between the range of activities that are too often treated separately.

With the emphasis on new care models described in the forward view taking hold across the country, local leaders in the NHS will need to ask themselves the question of what business they are in - are they running healthcare services, integrated health and social care services, or focusing on broader population health and wellbeing?

Hugh Alderwick is integrated care manager and Chris Ham is chief executive of the King’s Fund

Downloads

Flow Chart

Word

No comments yet