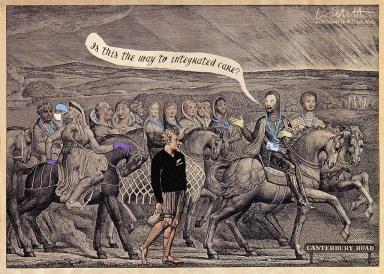

It’s one thing to advocate the idea of integrated care but quite another to make it work in practice − as Canterbury District Health Board has

Integrated care is an idea whose time has come. Norman Lamb’s pioneer programme will identify a number of areas that will be supported to develop integrated care at scale and pace. More importantly, the establishment of the £3.8bn Integration Transformation Fund in England means all parts of the country will be expected to develop plans for integrating health and social care.

‘The journey started in earnest when local leaders realised they needed to act urgently to avoid a substantial and unaffordable investment in hospital care’

Although the policy direction is clear, there is much less certainty about how to make a reality of integrated care in practice. Innovations such as those put in place in Torbay remain few and far between, showing how hard it is for organisations to work together on a sustained basis. All the more important, therefore, to learn lessons from areas that have achieved success.

A new report from the King’s Fund tells the story of Canterbury District Health Board in New Zealand, which has been on a journey of integration for nearly a decade.

The journey started in earnest when local leaders realised they needed to act urgently to avoid having to make a substantial and unaffordable investment in hospital care to meet the needs of a growing and ageing population. It was accelerated when the 2011 earthquake in Christchurch damaged hospital buildings, adding urgency to work already underway.

Enabler of change

Through many related initiatives, Canterbury has relieved pressure at hospital services and reduced the use of care homes. It has done so by increasing investment in services in the community, both to avoid inappropriate admissions and to ensure timely discharge from hospital. This is underpinned by a primary care system that has long performed well, and is now even stronger.

‘The mantra that has guided these developments is that of ‘one system, one budget’ − even though there is more than one funding source and several parts to the system’

As a result, although hospital services have not contracted, demand appears to have plateaued to the point where extra capacity will no longer be needed.

The mantra that has guided these developments is that of “one system, one budget” − even though there is, in reality, more than one funding source and several parts to the system. This served as a simple statement of the aspiration of local leaders to move from fragmented care to integrated care, joining up services around the needs of the population.

A key objective was to work across the whole system to enable hospitals to focus on those patients who really needed specialist care. Equally important was the desire to provide services to support people so they could be cared for in their own homes, and ensuring smooth and effective transitions of care between different settings.

Social care comes under the umbrella of health boards in New Zealand, and the existence of a single health and social care budget has been a further enabler for change. It has helped the board give effect to its plans without the complication of aligning funding streams from different agencies − although the board still contracts for many of its social care services.

Integration in action

The development of health pathways is a concrete example of how integration works. Pathways are local agreements or guidelines on how care should be provided, and are developed jointly by GPs and hospital specialists.

‘Canterbury’s story deserves careful study and adaptation if the commitment to integrated care is to be translated into practice’

The process of agreeing guidelines matters as much as their content because it increases clinical buy-in and, therefore, supports effective implementation. Almost 500 pathways have been put in place; they are reviewed and updated regularly to ensure they reflect changes in evidence and practice.

The Canterbury story is a powerful example of how improvements in care can be made by investing in staff and supporting them to change. Health board leaders put in place a number of development programmes aimed at training staff in quality and service improvement skills and techniques.

Over time, many hundreds of staff have taken part and this has resulted in many small changes, which together contributed to the transformation that is underway.

As an example of improvement occurring “from within”, Canterbury echoes experiences in organisations such as Jönköping County Council in Sweden and Intermountain Healthcare in the US.

The journey continues

A common characteristic in these organisations is a belief that a sustained and long term commitment to developing staff and equipping them with skills in quality improvement is the best way of improving performance. They have also benefited from continuity of senior leadership and have avoided the damaging effects of constant organisational restructuring.

Canterbury also offers lessons of particular relevance to the NHS, including scrapping its version of payment by results and developing a collaborative form of contracting known as alliance contracting.

It was able to do so because the organisational separation of commissioners and providers does not exist and, in any case, the scope for using contracting to stimulate competition is limited in a community where there is only so much that can be done to move contracts around. Care is provided by a mix of public and private providers, but always within the framework of “one system, one budget”.

The journey for Canterbury is by no means complete and not everything that has been tried has worked. Nevertheless, its progress was recognised recently by the New Zealand auditor general, who singled it out as an example of a high performing health board. The changes made seem to be sufficiently embedded to avoid further shocks, whether natural or organisational.

Canterbury’s story deserves careful study and adaptation if the commitment to integrated care in England is to be translated into practice.

Find out more

Chris Ham is chief executive of the King’s Fund

No comments yet