The NHS plan will set a direction of travel which looks set to create integrated care systems across England but there has been relatively little public debate over these bodies, notes Niall Dickson

A long-term plan for the NHS in England is imminent and it will set out how the health service should spend the extra £20.5bn – and the rest of its budget – over the next five years.

The scale of the health challenge has been well rehearsed – a doubling of over 85s in the next 15 years, those with more than one disease rising by 8 per cent a year and the prospect of having to build 60 new hospitals in the next decade just to keep up with demand.

There is a general agreement that the system will collapse without radical reform and that we must change the way services are delivered to relieve pressure on hospitals and make the NHS sustainable.

Yet as many in the service can testify, reorganising healthcare seldom achieves what its architects intend. The reorganisation in 2012 was aimed, like the First World War, to be the one that ended all others. Instead it has proved to be a bureaucratic nightmare, with even its early supporters acknowledging it is not fit for purpose.

As many in the service can testify, reorganising healthcare seldom achieves what its architects intend. The reorganisation in 2012 was aimed to be the one that ended all others. Instead it has proved to be a bureaucratic nightmare

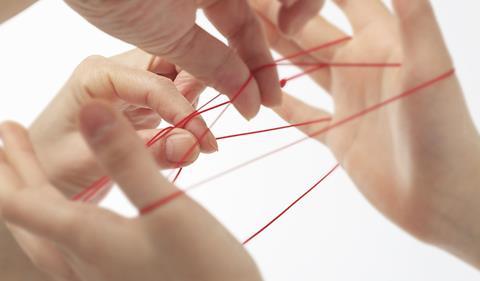

The driving force behind all this is the conclusion that only by joining up services and bringing teams of professionals together will it be possible to give people the right treatment in the right place at the right time and make the service sustainable.

The new buzz words are integration and “place based care” and there is certainly evidence both in this country and overseas that integrated services are at least a prerequisite for tackling the inexorable rise in demand.

The NHS has already embarked on this journey. Rather than thinking about organisations, it is being told to think about places. Rather than organisations focussing on their own interests, they are being urged to join with others to work out the best way to spend the local NHS pound in a way that generates the greatest health benefit for patients.

Seamless supply chain

But what will this mean in practice? Evidence from around the world suggests the key is to create a seamless supply chain – to develop new services which as far as possible prevent patients from becoming acutely ill and enable them – and the information about them – to move easily from one service to another.

That means encouraging and incentivising different physical, mental and social services not only to work more closely together, but at times to form single teams. It means knocking down the very real barriers that exist now between GP, community, social care and hospital services.

This is not as straightforward as it may seem. A survey of NHS Confederation members, the leaders of the service, suggested 86 per cent felt they had made little or moderate progress in taking integration forward over the last few years. (Letting Local Systems Lead NHS Confederation November 2018)

A survey of NHS Confederation members, the leaders of the service, suggested 86 per cent felt they had made little or moderate progress in taking integration forward over the last few years

There is concern at too much regulation and day to day interference from the centre and queries about how we make sure these services are accountable at local level. Thus far there has been little discussion about accountability.

There is a recognition too that other vital partners in this endeavour are not always fully involved in the new order.

The NHS plan will set a direction of travel which looks set to create integrated care systems across England covering around 1 million people each (though with variations, for example where there are metropolitan elected mayors). They will have responsibility for allocating health (and perhaps social care) spending and for agreeing local priorities.

Thus far, there has been relatively little public debate and less public understanding of these bodies which currently have no statutory powers and are in effect coalitions of the willing. But that will change, and these will or should be the engine rooms driving new ways of delivering care in every part of the country.

Tests for integrated care approach

Three tests need to be applied to this new approach.

First, to whom will the new structures be accountable at local level? Thus far, there has been little mention of this but if we are to achieve major changes in the way services are run, it will be vital that they command local support.

Second, will the government make sure that all providers of NHS and care services, whether they be from the statutory, independent, voluntary or community sectors have an equal place around the table? We need the capacity and creativity of these groups to complement and challenge NHS organisations.

And third how do we make sure that integrated care systems do not become cartels or “airless rooms” in which local providers carve up the money between themselves.

At the moment, we have clinical commissioning groups which are separate from providers, and everyone accepts we need to move to something which is more strategic, and which involves more of a partnership between commissioners and providers.

We must get this right – the plan is a once in a generation chance to shape an NHS for at least the next decade.

No comments yet