New research from Edge Health shows that London is better prepared than other regions to cope with covid-19, but all regions will face substantial pressures in coming weeks, writes George Batchelor

The NHS currently has in the region of 150,000 beds (102,000 are overnight acute beds). Our modelling has shown that even under a mitigated growth scenario with vulnerable people being isolated, doubling that capacity may not be enough to meet the additional demand generated by covid-19.

To put it another way, even if the entire NHS bed capacity were recreated in just six weeks we would still have patients in need of a bed by the middle of May. This pressure is most significant for patients that need critical care beds with ventilation support, which if not met will likely result in increased mortality rates.

Regional variations

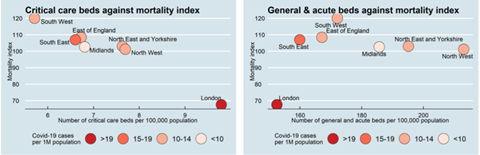

Behind this macro challenge, there are significant regional variations in terms of the number of hospital beds and critical care beds that are currently available. There are 30 per cent more critical care beds per head of population in London than the south west, although it is lower in terms of hospital beds.

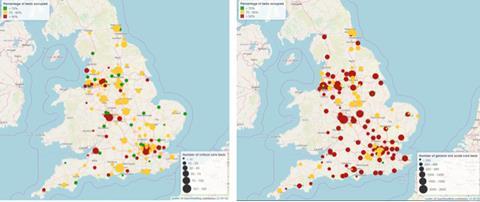

Arguably this existing bed base may be adequate for “normal demand” based on existing demographics. The unique challenge from covid-19 is that it appears to result in significantly higher mortality rates for older people who tend to be based in areas where there are fewer beds per head of population. For example, the maps below show that existing bed capacity, much of which has high occupancy, is located away from rural communities where the age profile is older.

In the short term, available bed capacity is important to manage the initial wave of severely and critically ill people. In England critical care beds were reported as being 83 per cent occupied in December – this starkly contrasts to Italy which had reported occupancy levels pre-Covid-19 of 33 per cent, although this may in part be due to different reporting methodologies.

Regionally it appears that more beds are available in London compared to the south west. This may be due to challenges in being returned home in rural communities.

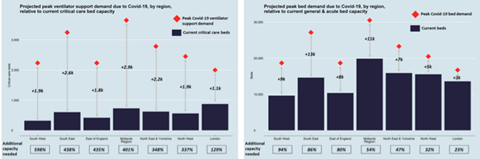

Even if this capacity were available, estimating the expected demand from people that will get ill from covid-19 at its peak suggests there is a significant gap across all regions.

Based on our analysis, the shortage is largest for critical care where between 130 per cent (London) and 600 per cent (south west) additional beds are required to meet expected demand in the coming weeks, even without considering the demand from patients without covid-19. For hospital beds, the shortage is less significant with an additional 23 per cent (London) to 94 per cent (south west) additional beds required to meet demand, although far more of these are required in total.

One aspect of the unfolding crisis not yet fully understood are regional differences in the growth rate of cases. Currently, reported cases (which may be a fraction of the total) are highest in London where there is a younger population that is less likely to need a bed – it is also the region with the largest number of beds. This and the relatively higher number of unoccupied beds in London may have made coping with covid-19 to date relatively less challenging than it will be in coming weeks and across other regions.

This contrasts with other regions where we would expect the higher number of older people to translate into higher mortality (based on an age-weighted mortality risk index for covid-19, which is based on data from Italy and Korea), but there are fewer critical care beds.

Creating additional capacity (staffing, beds, etc), taking measures to reduce the level of overall demand and identifying solutions to get and keep people home as safely and quickly as possible should be a national priority.

5 Readers' comments