Contrary to popular opinion, the NHS has not been cut to the bone, our latest leadership survey suggests. Meanwhile, managers continue to be concerned about quality, safety and the forthcoming election – and are still waiting for the ‘Simon Stevens’ effect. Alison Moore reports

NHS managers are experiencing Groundhog Day, with the same issues and solutions dominating their agenda as last year.

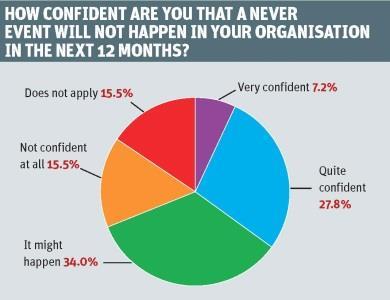

‘Around half the respondents were not confident that a never event would not happen in their organisation’

That’s the conclusion from the second HSJ/GE Healthcare Finnamore leadership survey with answers to a range of questions showing a remarkable continuity with last year.

There is no sign of a “Simon Stevens” effect with changed priorities among our respondents – the majority of whom classify themselves as senior managers, with around one in four who are board members. “Having a new NHS England chief executive has an obvious disruptive effect but there is no sign that this is affecting managers,” says GE Healthcare Finnamore partner Jonathan Pearson.

This year has been marked by the focus on quality and safety with the continuing impact of the Francis report, and the Berwick and Keogh reports. Is that having an impact on the ground with managers feeling more confident about the services they provide?

Apparently not. “Both years, around half the respondents were not confident that a never event would not happen in their organisation in the next 12 months,” says Mr Pearson. “It’s quite remarkable that it is consistent two years running, which shows last year’s response to this was not a quirk.”

Top priorities

But improving patient safety and minimising harm is still top priority for our respondents. “It is right up there. Lots has been going on – Mid Staffordshire, Francis, Berwick and all the fallout from them, not to mention the board assurance process, the Care Quality Commission’s new approach – lots has been happening but nonetheless people feel that a never event might happen,” says Mr Pearson.

“It raises the question in my mind that this is a top priority; but what are the barriers? All of the things that have happened may not have tackled those barriers. Are we tackling the right things? And do we need to better translate the intent – respondents say quality and safety is a top priority - into reality?”

And he points out that the views of survey respondents - many of whom would be closer to the “shop floor” than board members - on this suggested there may be a “board to ward” disconnect on this. “The consistency across the two years does make it more compelling,” he adds. “My guess is that there won’t be a magic bullet which will improve this. It won’t be just about processes and systems. My feeling is there is quite a lot of culture in there.”

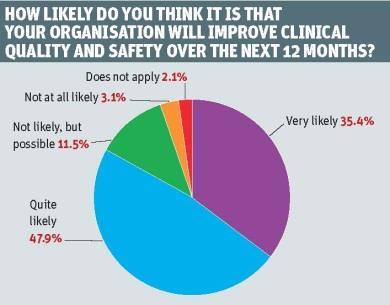

But there is great optimism that organisations will improve clinical quality and safety within the next year – even though this will cover the general election period. Overall, the proportion expecting to improve had shifted up slightly compared with last year with five out of six saying it was very or quite likely.

Surprising opportunities

Mr Pearson has doubts about this optimism. “I don’t know that people have really thought about the period covered by this question including the general election. It does seem optimistic to expect to improve operational clinical processes and safety through a general election period.

‘People seem to be saying they are not at the end of the road with these savings’

“Some improvements in quality and safety will be dependent on reconfiguration of services – and that is something the general election campaign, and the purdah period beforehand, will have an impact on.” However, other improvements – for example in clinical care – may still go ahead unhindered and the balance of where the improvements are likely to come will vary between different organisations. In some health economies, reconfigurations will have already been made or are a long way in the future and the focus will be on other means of improving quality and safety.

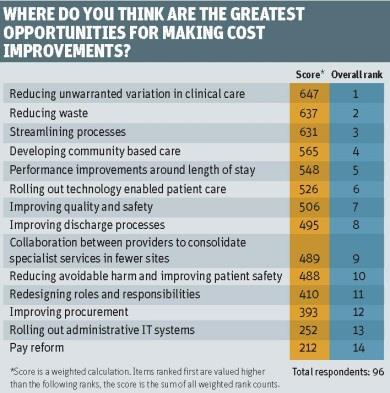

But all health economies will face challenges around making savings and there were some surprises in where our respondents thought the opportunities for this lay. Reducing waste moved to second spot, from sixth last year, behind reducing unwarranted variation in clinical care. Mr Pearson points out this comes despite years of trying to save money through the Nicholson challenge and reducing waste (of all types) being seen as an easy win, involving relatively little pain for organisations.

The top three answers were all things which could be done internally, without necessarily having to cooperate with other NHS or other organisations. This may reflect the perspective of respondents – predominately managers below board level.

“But it is contrary to the view that what is left to do to make savings is across the whole health economy – that all the savings which could be made just by reducing waste have already been delivered. People say they have cut to the bone but that is not coming out in the survey, people seem to be saying they are not at the end of the road with these savings.”

Fat to lose

That managers feel there is still fat to be cut does suggest that the NHS had substantial efficiencies to make before the Nicholson challenge was introduced, he says. Relatively few felt that they had exhausted all available options on cost savings and this would now limit further improvements.

Increasing demand was seen as the main constraint to cost improvements, with lack of capacity among middle managers to deliver changes a relatively close second.

‘I suspect that two or three years after the election a lot of service change reviews could work through to trust mergers’

“There is a consistent message that middle managers are key to change but often overlooked. You don’t hear a lot about support programmes for middle managers,” Mr Pearson says. But he points out that, with another question on what would help to deliver change, middle manager capacity was towards the bottom, as it had been last year, making the results “consistently inconsistent”.

Integration had risen on this question while clinical leadership had gone down – perhaps suggesting managers felt they now largely had this in place.

Cultural barriers were still seen as the main barrier to developing integrated care – despite the need to remove barriers between different parts of health and social care having been talked about for years. Does this suggest that work on this is very slow or that the cultural issues are so intractable that progress is stalling?

And there was also consistency in the proportion of respondents who expected their organisation to be heading towards a merger in the next three years. Mr Pearson points out that the last year has seen mixed messages on mergers: the Bournemouth-Poole one was rejected, making some people nervous; some planned mergers have been abandoned or delayed for other reasons, but on the positive side the Dalton review has raised the possibility of hospital chains.

Appetite for change

“There are a number of whole system reviews around the country involving service changes and post-election may give rise to organisational change,” says Mr Pearson.

“There is quite a lot happening, I suspect that two or three years after the election a lot of that could work through to trust mergers. The interesting thing will be the appetite of a new government for these changes.”

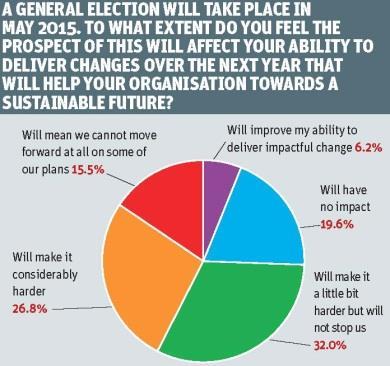

But there is a sting in the tail with the approaching election. Close to 75 per cent of respondents felt that the prospect of this would make it more difficult for them to deliver change over the next year. Around 20 per cent felt it would make no difference and an optimistic few felt that an election campaign would make it easier for them.

“The race is wide open which will create a lot of uncertainty,” points out Mr Pearson. “How does that play out into health policy, especially hospital reconfiguration and organisational change?”

Politicians often find themselves caught between promoting access to local services and a trend towards larger centres which may offer better outcomes and enhanced safety - but will involve some people travelling further.

“I think it is potentially quite an uncomfortable position for politicians,” he adds. “The instinct for health service managers is to centralise to make things easier – but does that give enough thought to keeping things local?”

Disruption in 2015

The run-up to an election and the period immediately after are often disruptive – in 2010 in particular, as the change of government led to many work programmes being stopped.

“Our NHS middle managers are saying that next year will be harder than this year. There will be more uncertainty,” he says. He suggests that some areas will now delay controversial changes until after the election. “People have been rushing to try to get some of the particularly sensitive things done,” he says.

But as Mr Pearson points out, the NHS does not always behave as planned in an election period.

“Undoubtedly there will be chief executives out there who will experience an event in their organisation that attracts the focus of national media.”

There can be unexpected events that cause political difficulties or even individual cases that end up being highlighted – as in the notorious “war of Jennifer’s ear” in the 1992 campaign when a young girl’s ear operation dominated headlines for several days.

Whatever happens, the next year looks like a challenging one for NHS leaders

No comments yet