The 2018 target of a paperless NHS is laudable in theory but is it realistic in practice? Alison Moore reports on an HSJ survey, in association with CCube Solutions, that suggests widespread scepticism, and reports on a lively roundtable in which experts wrestled over the factors that might help in hitting the 2018 goal

In 2013, health secretary Jeremy Hunt called on the NHS to become paperless by 2018, saving “billions” of pounds and catching up with the rest of the economy as it embraced the digital revolution.

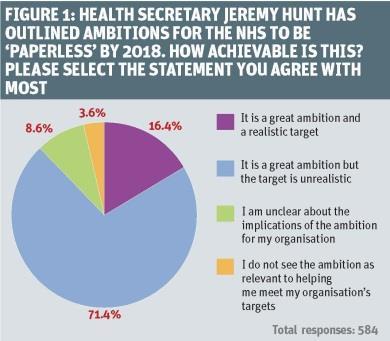

Two years on, that prospect can seem as distant as ever, and an HSJ survey has shown widespread scepticism that this deadline is achievable. As many as 71.4 per cent of those who responded to our recent online survey felt it was a great but unrealistic ambition and only 30.7 per cent felt that NHS leaders had enough knowledge of the clinical and efficiency benefits of better IT systems.

So what are some of the barriers to more widespread adoption of paperless systems in the NHS - and how have some areas managed to overcome them?

HSJ brought together a panel of policy makers, commentators and users to give their perspective on these and other issues.

There was a general acceptance that there were benefits to be reaped from going paperless - but these benefits partly came from the opportunities to change the way things were done when moving to a paperless system as opposed to simply replicating the paper system on a computer.

However, there were concerns about how such significant changes could be achieved by 2018 and what the constraints were - especially money.

The panel

- Adele Waters executive editor, HSJ (chair)

- Maureen Baker chair, Royal College of General Practitioners

- Matt Butler member, RCN e-health forum steering committee

- Saffron Cordery director of policy and strategy, NHS Providers

- Neil Darvill director of health informatics, St Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals Trust

- Jon Holmes head of informatics programme, Aneurin Bevan Health Board

- Candace Imison director of healthcare systems, The Nuffield Trust

- Vijay Magon managing director, CCube Solutions

- Paul Rice head of technology strategy, NHS England

- Tom Williams retired consultant paediatrician, Aneurin Bevan Health Board

NHS Providers director of policy and strategy Saffron Cordery said: “Money, in many ways, is the backdrop to so much of what we are grappling with but it is not everything. However, all of the operational and strategic planning would be hugely aided by longer term contracting and budget setting from the centre.

“How does any organisation manage to develop an effective strategy if they are looking at year-to-year funding?”

But all organisations were also operating in a time of austerity where pots of money like the technology funds - which would help organisations invest in the skills and technology needed to go paperless - had been raided to support the NHS through a difficult winter.

‘Only 30.7 per cent felt NHS leaders had knowledge of the benefits of better IT systems’

“We need to get buy in for this [going paperless] and that is absolutely fundamental,” Ms Cordery added. “To get buy in we need to make the clinical case and that is where the challenge will come.

“But I also think we need to create the strategic headroom for provider boards to be able to invest their operational and strategic time in this.”

She described the shift to paperless as a new way of working which was akin to the shift to seven day working.

“This is not just about not having hundreds of filing cabinets but about transforming the way we deliver care.

“It needs adequate investment in time and effort across provider boards to have the strategic headroom to look at all the challenges that arise.” This was particularly difficult with everything that was going on for boards at the moment, she added.

GPs lead the way

But Maureen Baker, chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, had a positive story to tell. General practice was largely paperless already, she said, and the rest of the NHS could learn from its example. “When I work in practice, I struggle to find a piece of paper in the room,” she said. “I usually end up taking it out of the printer!

“The big part of the NHS which struggles is acute services but I strongly feel that is not the [whole] NHS. It can be done and there are lots of reasons why it has happened in general practice and not in the acute sector.”

Key to these was clinical engagement - GPs had bought into paperless many years ago, whereas the National Programme for IT had not got this engagement. GPs’ status as independent contractors, able to make decisions for their practices, had also helped.

“GPs picked up on this very quickly, first and foremost for safety reasons largely around prescribing,” she said.

Now a billion prescriptions a year came out of general practice: to do those all by hand would be inefficient and unsafe.

But, she pointed out, the move to paperless systems had cost practices money. “When I was a partner and we bought our first system it cost us £20,000.”

She highlighted the value of the NHS number as a unique identifier - with strong safety reasons for its use - but added it is not universally employed when people come into contact with the NHS.

NHS England’s head of technology strategy Paul Rice said that the latest research showed that the NHS number was used more than 98 per cent of the time when care transferred between two organisations - although he agreed that it was not always universally used within organisations.

And he suggested that the NHS number had a crucial role to play in ensuring continuity of care - because identifying the right patient was important in preventing care breaking down. However, he suggested, there was a need to look at the inclusion of other links in the chain, such as ambulance services and hospices.

Dr Baker added: “Many clinical staff think that IT stuff is admin, it’s not what they do. But when we talk about the NHS number we are really talking about the right patient, right care and that is when it starts to make sense [to hem].”

Her arguments were strongly supported by John Williams, a retired paediatrician from the Aneurin Bevan Health Board.

He said that, in contrast to general practice, secondary care IT systems have tended to be about administration with little clinical engagement.

And Matt Butler, a member of the Royal College of Nursing’s e-health forum steering committee, said: “The kind of diktat we get - achieving a paperless NHS by 2018 - seems unrealistic. Let’s focus on the benefits.”

But Mr Rice insisted that the paperless NHS was not a diktat and was more “shorthand”. “What is it trying to evoke and how do we deliver what it is trying to evoke?” He referred to people’s experience in other parts of their lives and how digital technology has changed this.

But it was necessary to make and remake the clinical case for change - and to make the business case for change.

Vijay Magon on change from the bottom up

Health secretary Jeremy Hunt wants the NHS to be paperless by 2018. Mr Hunt wants digital records so patients’ information follows them.

But unlike previous large scale, top down directives, he wants this driven bottom up.

By 2018 any crucial health information should be available to staff at the touch of a button.

Cost effective solutions based on established electronic document and records management (EDRM) technologies offer the chance for the NHS to embrace a culture of compliant information management practice delivering healthcare which, if not paperfree, is paperlite.

There is no magic bullet solution - just a common sense approach which focuses on specific processes to ensure that the solution delivers what is expected of it.

The core technology has been around for over 35 years, and is in use across many industry sectors. Lessons have been learnt through careful application of EDRM technologies.

Systems have become more affordable and are delivering real and measurable benefits.

The key points to keep in mind are:

- Simply digitising paper records is not enough - through generation, management, and integration of electronic records, the solution must offer facilities to stop producing new paper.

- Patient information resides on many disparate systems within trusts. The electronic medical record cannot sit in a document management system that remains unconnected with other hospital systems and processes. Information must be exchangeable and shareable amongst all practitioners: interoperability is a must.

- To be optimally effective, the electronic record has to be delivered to key users when and where they need it. A solution which offers a standard interface for all will provide limited functionality to most.

A number of trusts took the bold step towards paperless healthcare some years ago.

By paying great attention to the underlying processes, these trusts have achieved paperlite healthcare using EDRM.

Given the bad press about large scale IT implementations, two valuable lessons must be learnt:

- Not all trusts are ready for the top end solutions - each must accommodate the technology and its implementation gradually to suit local conditions including budgets, IT infrastructure, user training etc;

- A core application cannot be driven top down without involving the people who will actually use it and who will be held accountable.

While it is good to see that the Hunt ambition is accompanied by money, each organisation must make its own case for improvement and demonstrate willingness to change. Simply throwing cash at a problem will lead to yet another IT failure. The bottom up approach means that the digital revolution in the NHS is achievable - gradually and without committing astronomical sums to large scale IT projects.

Vijay Magon is managing director of CCube Solutions

Mr Butler pointed out that GPs had had the freedom to make decisions on what IT they wanted. “That’s something where acute trusts are lagging behind. From my experience as a nurse, there is a kind of learned helplessness in hospitals.”

People were often used to doing things in a certain way and some tasks - such as using graphs - could be hard to do using standard packages, although touchscreen technology could help. “What people use paper for is not always replicable digitally,” he said.

Ms Cordery pointed out the setting that care was delivered in was very relevant to this debate - for example, the ambulance service had particular needs around mobile working. Community and mental health providers had challenges but also opportunities to deploy technology to best effect.

“We know that the public sector can lag in adopting technology which is needed,” she added. “I think the next three to five years is when we are going to see a real leap as we move towards the integration agenda.” This would rely on systems which were interoperable and connected to each other. Ultimately local authorities and voluntary bodies needed to be included in this so they could all communicate with each other.

She suggested it was a little unfair to talk about “learned helplessness” as some organisations had made significant steps forward, though there was a challenge to get everyone using technology. There was a need to understand the starting point before saying organisations were slow to adopt.

‘The next three to five years is when we are going to see a real leap’

Neil Darvill, director of health informatics at St Helens and Knowsley Teaching Hospitals Trust, said there were successes. Trusts could make a significant investment in technology with a small percentage of their turnover.

You need an organisational understanding of the kind of benefits you can get back from that investment,” he said.

Commitment from the top was important, so there was a need to influence boards so that this became a focus. “If a trust board decides to do something it usually pretty much succeeds,” he said.

But how could that be achieved, asked HSJ executive editor Adele Waters, who chaired the debate. What was needed to make boards put this higher up on the agenda?

Mr Darvill said targets could be the way ahead. “Organisations will absolutely focus on these things because of the high profile nature of these targets. Most boards are probably quite keen to engage and invest in the infrastructure agenda but struggle to find a way to do it that gives them the right assurance. You get a hiatus where there is an anxiety about how to proceed.” Some of this may be because past investments in technology in the NHS had been “black holes”, which concerned boards, he added.

Jon Holmes, head of the informatics programme at Aneurin Bevan Health Board, raised the question of how IT was represented on trust boards. At the moment there is a tendency to give IT as an additional responsibility to an executive director with other roles as well.

Mr Butler said the development of the chief clinical information officer was becoming increasingly important but there was a question around whether it was sufficiently valued.

Mr Rice said how it was reflected in job plans was very varied: “There are a number of places where best practice and experience are coming together. There is an increasing sense of the need to identify best practice and to celebrate it.”

Procurement parallels

Ms Cordery pointed out the similarities with procurement in the NHS. “It is a massive strategic issue. It needs to take high priority on any organisation’s agenda but it is often overlooked.”

She also drew a parallel with how procurement had veered between being centrally run and locally determined, being outsourced and being done in-house.

She suggested many people had been scared by what had happened with the National Programme for IT. But while IT investment was something people had been thinking very carefully about, it was now time to act because of its fundamental importance to how organisations would operate in the future. “It is right up there if you are going to make your business a success. But what we need to do is help people make the case for it. That really is fundamental. There are so many compelling cases we need to make.”

Mr Darvill said there needed to be more collaboration and sharing, with trusts learning from what others had done. “Sometimes boards don’t get enough information to make a wise decision. Informatics in a single organisation is often too small a service and struggles to attract people of the right calibre.” There could be significant cost savings if organisations collaborated.

Mr Holmes added: “The key thing is a champion: if that champion essentially has a clinical background that can really move things forward.”

One of the arguments for investment in IT systems which allow different organisations to share information is that it aids integrated care.

But Candace Imison, director of healthcare systems at The Nuffield Trust, said: “The evidence shows that you can get really good integration without a shared care record. It is the way that people relate to each other that drives really good integrated care. I would not pin integrated care on IT. Having said that, of course, it facilitates it.”

In the US, for example, access to hospitals’ records helped nurses provide telehealth services more effectively.

She pointed out how far IT had developed - when she had been involved in planning an electronic patient record at one site the key question had been where would the cables go.

‘The key thing is a champion: if that champion has a clinical background that can really move things forward’

And she warned procurement in the NHS can take so long that it is out of date by the time the equipment is installed.

Ms Imison hesitated about taking too much from the experience of GP practices, which were typically quite small. Acute trusts were larger organisations and had much more complex processes. This could explain why they might find it more difficult to go paperless. But she found it hard to understand why IT had not taken hold in community services.

Mr Rice pointed out there were relatively few free-standing community trusts. “Lots of community services are an element of very complex organisations - acute trusts.”

The integrated digital care technology fund would bring productivity improvements, which is why it had been embraced by applicants, he added.

Its focus was increasingly on capabilities rather than specific bits of kit, he added.

Ms Waters suggested that, by linking the technology to capability, organisations would be making the case for investment. Mr Rice said: “The vast majority of clinicians, when you talk to them, will bite your hand off for change.”

But Ms Cordery said: “You have to put your core infrastructure in place. That is a big procurement issue. But how you then tap into it and use it can be a local decision that is service led.”

Innovative solutions might help: one partner might have the ability to invest while another might have the ability to use the technology to the best effect.

Ms Imison suggested there was a capability and skills gap within many organisations when it came to IT. “We don’t tend to have the informatics skills within trusts and we have not developed them. It should be a skill set of all leaders. It is not helpful as a leader to have no insight into the opportunities and challenges that technology has for your organisation.

“My perspective is that we have informatics people who are deeply ignorant of the clinical processes that they are supporting.”

She gave the example of a common challenge in hospitals being the number of rapidly-changing medications some patients had. It could be very difficult for doctors to work out which prescriptions were current and this could be a safety issue.

Dr Williams said: “I think it is terribly important to look at this in a positive way. There is progress. I have seen some enormous benefits from the introduction of these systems.” Electronic discharge letters, for example, had put information in the hands of GPs much more quickly.

“This is not just something that Jeremy Hunt says we have to do - it is actually progress. The trusts that have moved in that direction appreciate that.”

He cited the example of growth charts used in paediatric departments. These were frequently impossible to use with standard packages but he had been involved in the development of software which allowed practitioners to easily input this information and update the chart.

This could improve clinical care and was responding to a clinical need - and clinicians had appreciated it. He had looked at using off the shelf solutions but in the end had decided to develop a dynamic growth chart - a growth chart for children that can be changed to incorporate new information over time as the child grows.

He pointed out some countries assigned citizens individual numbers which not only functioned like the NHS number but were also the gateway to other services, such as banking. In these cases, everyone knew their number.

Mr Holmes outlined some of the questions about going paperless in secondary care, which had to deal with a massive workflow. Should systems work on people’s own mobile devices? What about security in these cases? He said he actively encouraged clinicians to come up with ideas for improvements in the way systems worked and received many emails from those who wanted systems that could do more. The problem now was dealing with all these competing demands.

‘Boards need to sit down and understand the totality of their business and the money available’

Mr Darvill suggested that not enough was always done to get clinicians and “techies” in the same room. “Those of us that try that get success,” he said. Mr Rice pointed out that some of the processes around applications for funding did require people to get together and to start discussions about aspects such as interoperability.

Mr Williams said there was a contrast between Wales and England. “The [Welsh] infrastructure does make it easier for us. We all log into the same portal and can see the same records. Staff in Wales also have unique numbers.”

Ms Waters asked if a five year plan was needed to make certain the technology fund was shored up. “How can we protect funds for this? We agree it is an important agenda but there is not the security for people.”

Mr Rice warned that this was a “business as usual” agenda. “Boards need to sit down and understand the totality of their business and the money available. We should redouble our efforts to the next comprehensive spending review to point out to people the extent to which the NHS may need additional support around this agenda.”

But the NHS would need to present a case around the benefits spending would deliver. “That business case is not made by me at the centre but by those at the frontline.”

This was not about an IT agenda but a transformation one, he added.

Ms Cordery questioned the 2018 target, saying that 2025 might be more realistic and 2018 was a massive ask for the NHS. “If there genuinely is a push towards moving us there quickly, then we need more money behind it,” she said.

Mr Darvill added: “We have to be very mindful of what happened with NHS Connecting for Health. Most trust boards just had their feet up and waited for some organisation to give it to them.”

This meant they were not taking responsibility for what was happening. If boards were really serious, then they did need a business as usual approach and needed to make investment.

“You have to have a baseline position of 2 per cent of your organisation’s income being spent on informatics or you will not be able to do this,” he said, adding that transitional funding would be very welcome.

But Ms Imison pointed out it was increasingly important to realise that it was going to be hard for every trust board to deliver a balanced budget next year and there would also be a cashflow problem.

Ms Cordery added: “The first priority is to keep the ship upright and organisations would not be looking at transformation if they could not keep the ship upright. You can imagine the headlines - trust invests £xm while patients are turned away at the door.”

But Mr Rice stressed that the Five Year Forward View did not talk about 2018 as a target but does talk about the momentum which is needed.

Other documents such as Personalised Health and Care 2020 talked about 2020 for most care settings with 2018 mentioned for primary care, urgent and emergency care and key transition points.

“It [a paperless NHS] is a deliberately ambitious target,” he said. “It is an articulation in two words of what we have all acknowledged is a sophisticated and complex agenda.”

Drawing the debate to a close, Vijay Magon, managing director of CCube Solutions, said interoperability was one of the challenges that needed to be focused on.

Mr Magon pointed out that there was legacy information in many institutions which was not automatically interoperable. “Something has to be done to it to make it interoperable,” he said.

Each trust had to find its own money for this and it was necessary to fight for money because there were so many competing demands - and that was why it was not happening in the way they wanted it to.

But, asked Ms Waters, was this worth fighting for? Mr Magon said it was: “It is delivering tangible and measurable benefits.”

The survey

HSJ’s paperless NHS survey has revealed enormous scepticism among healthcare professionals that this transformation can be delivered by 2018 - but there is strong support for the concept.

The survey was carried out at the end of last year and was completed by 573 people - including healthcare leaders, clinicians and IT professionals.

More than seven out of 10 of them felt the paperless NHS was a great ambition but was unrealistic (see figure 1, above).

They identified several key barriers. The top one was seen as the lack of joined up working between different parts of the NHS, with lack of interoperability between different vendors and systems, and the variety and diversity of clinical systems next most important.

When the survey results were broken down by job title, managers also saw funding for systems as important.

But the survey showed concern about the understanding of NHS leaders: 69 per cent felt leaders did not have enough information about the potential benefits to efficiency and clinical working that improved IT systems could deliver. As many as 94 per cent of respondents felt this could undermine Mr Hunt’s ambition.

Forty per cent would support mandated extra training for leaders to improve their understanding while 70 per cent wanted to see more learning from other organisations with success in IT.

Three quarters felt that contracts should be used by NHS providers to drive interoperability and cooperation between different parts of the system.

But when it came to integrated care, there was concern this would be undermined by the lack of integrated electronic records.

‘CCGs and area teams were seen as best placed to oversee progress’

A total of 56 per cent felt that these were needed to deliver integrated care and almost three quarters felt that the delivery of integrated care would be held back because not enough attention and resources had been put into the technology which underpinned it.

Clinical commissioning groups and NHS England’s local area teams were seen as best placed to oversee progress towards integrated care records.

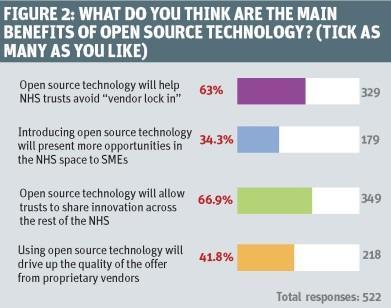

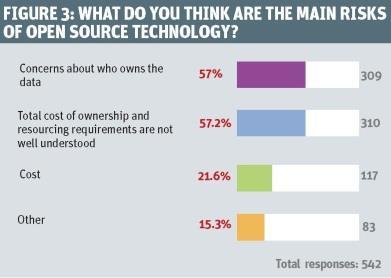

NHS England has suggested greater use of open source in the NHS. Almost two thirds of respondents backed this. Top benefits were seen as sharing innovation and avoiding “vendor lock in” (see figure 2, above). However, there were concerns (see figure 3, below). The two top ones were who owned data when open source software was used and lack of understanding of its costs and the resources needed.

1 Readers' comment