The 29 ‘vanguard’ sites developing new models of care for the NHS will face huge scrutiny. Ingrid Torjesen reports on an HSJ roundtable that debated their merits, flaws and chances of success

How much impact will the new vanguard sites for developing new models of care have on the NHS? On 9 March, the night before the successful vanguard sites were formally announced, HSJ gathered some of those involved in the bidding process to address this crucial question.

‘Twenty nine have been selected as vanguards’

The discussion, sponsored by Celesio UK, focused on the potential for the sites to improve health and care services to an ageing population with complex health conditions.

NHS England received 269 vanguard applications, 63 of which were taken through to workshops. At the workshops, applicants were asked to present their vision for what they were trying to achieve, including the services involved, the patient population targeted, how success would be measured and what support they would need from the national programme.

A total of 29 have now been selected as vanguards.

There are two main models in the vanguard programme: Integrated Primary and Acute Care Systems (PACS) and Multispecialty Community Providers - plus another model focused on enhancing health in care homes.

The participants:

- Professor Rob Darracott chief executive, Pharmacy Voice

- Fiona Edwards chief executive, Surrey and Borders Partnership Foundation

- Sir Sam Everington London GP and chair, Tower Hamlets CCG

- Chris Gordon chief operating officer, Southern Health Foundation Trust

- Alastair Henderson chief executive, Academy of Medical Royal Colleges

- Sam Jones director, New Models of Care, NHS England

- Dr Barbara King Birmingham GP and clinical accountable officer, Birmingham Cross City CCG

- Michael Macdonnell head of strategy, NHS England

- Alastair McLellan (roundtable chair) editor, HSJ

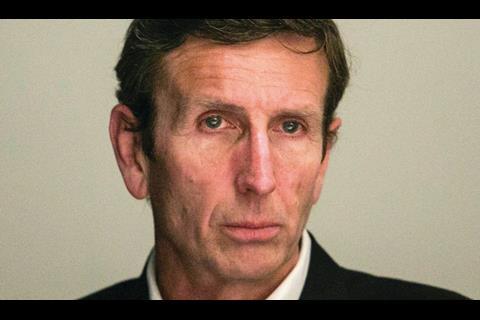

- Dr Keith McNeil chief executive, Cambridge University Hospitals Foundation Trust

- Sally Morris chief executive, South Essex Partnership University Foundation Trust

- Professor Ian Philp chief medical officer, Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals Trust

- Dr Gavin Ralston chair, Birmingham Cross City CCG

- Dr Dan Roper chair, Hull CCG

- Dr Derek Thomson, medical director, Northumbria Healthcare Foundation Trust

- Cormac Tobin managing director, Celesio, parent company of LloydsPharmacy

- Wendy Wallace chief executive, Camden and Islington Foundation Trust

- Dave West commissioning bureau chief, HSJ

- Rob Whiteman chief executive, Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy

- Andrew Willetts public sector and healthcare services director, Celesio

Sam Jones, director of New Models of Care at NHS England said the workshops had shown the huge amount of positive work going on and the need to share this. Impressive partnership working and “strength and breadth” of leadership across primary care, secondary care, community, mental health and social care was also evident in some, although not all, of the areas, she said.

“We still probably have some work to do around citizen and patient engagement,” she added. While some applicants had talked about having conversations in town hall meetings, “what we were looking for and we will be pushing quite hard through the vanguards programme is how patients and citizens are really truly involved in their care, in shaping the care”.

Ms Jones said not everyone had given enough thought to how the changes would be delivered including, for example, what would be needed in terms of contracts. “People spent a lot of time looking at what,” she explained, “not so much as I would have hoped to have seen on the how and the leadership and the organisational development part of it.”

What had impressed NHS England head of strategy Michael Macdonnell was the way applicants had approached the process with a real sense of what they could do as a peer group. “That is really collective leadership in action,” he said. However, he had been disappointed that applicants had not put more emphasis on workforce.

“They talked about buildings or fancy names, but didn’t really describe how people would work differently together,” he said.

Dr Keith McNeil, chief executive of Cambridge University Hospitals Foundation Trust, had sat in on one workshop and been impressed by the enthusiasm for change. “It was good to see clinicians at all levels stepping up to take the lead on this, which I think is something that is desperately needed,” he said.

‘Not only do the vanguards need flexibility, they also need time’

“In terms of the models I don’t know which one will work best,” he added. “Form should always follow function,” so it was important not to be too prescriptive and to allow flexibility, he said.

Not only do the vanguards need flexibility, they also need time, because transformation of this sort takes years, said Rob Whiteman, chief executive of the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy. The vanguards are striving for systemic or strategic productivity - spending money in the right place in order to get productivity from the system overall, as opposed to targeting the easier win of more efficient procurement.

“Reform movements start off with the right intentions, but then circumstances take over a bit,” he said. With growing financial pressures on both the NHS and local authorities, there was a danger that that could take over the agenda.

“On the whole if you put two overspending systems together, it doesn’t instantly save money,” he explained. “My worry is that in six months’ time they’ll be another set of vanguards.”

Dr Derek Thomson, medical director of Northumbria Healthcare Foundation Trust, said it was important to see vanguard sites not as pilots but as part of the journey. Although Northumbria applied to be a vanguard, its integration journey had begun 14 years ago, he said. “If the organisational forms change, absolutely everything can be done if you’ve got the right relationships and spend long enough developing and fostering those relationships.”

- Vanguard sites will not access full £200m transformation fund

- NHS England reveals new care model ‘vanguard’

Integration possibilities

HSJ editor Alastair McLellan, who chaired the roundtable, asked what felt different about the vanguard process and its aims compared to what had gone before, and whether it was likely to be more successful.

Sir Sam Everington - chair of Tower Hamlets CCG, a GP at Bromley by Bow health centre, and one of the national leads for the new models of care - responded that, this time, it was about partnership working that looked at things from the patient’s perspective. “They’re aiming for a partnership across the whole of the patient pathway.”

Alastair Henderson, chief executive of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, said feedback from clinicians and medical colleges was that the vanguards made sense, although perhaps earlier iterations had not and therefore had not got the necessary engagement.

People from the acute sector recognised they needed engagement in mental health and primary care, partly because the problems they were having were only going to be solved by thinking outside what happened in the large shiny hospital, he said. “Surgeons are saying ‘well actually I need that to be sorted because otherwise I’m never going to get off this treadmill,’ that seems to me as being different.”

“One really interesting thing that I’m picking up from various colleges is what we actually need to do is to concentrate as much on the relationships as on the set of structures,” he said.

One of the reasons why vanguard sites were more destined to succeed than initiatives that had come before was that general practice could not recruit doctors, said Dr Dan Roper, chair of Hull CCG. GPs would like the programme because it was the only way they could deliver care with a shrinking resource, he said.

“The change in the workforce is actually driving innovation.”

There had been a move towards intermediate care in the early 2000s and it had been developing well, said Professor Ian Philp, chief medical officer at Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals Trust - and a former national clinical director for older people. But then a policy decision had cleaved the healthcare system into two: the NHS and social care.

‘It really feels like there is a social movement happening’

“The structural and functional mechanisms for integration were lost,” he said. “The tragedy is that two more years would have done it, because Hong Kong took the English intermediate care model and implemented it and got rid of delayed discharge completely.”

There was a big risk that integration had been “the flavour” for about five years but a big policy shift could again destroy the work that had been done, he warned. Wendy Wallace, chief executive of Camden and Islington Foundation Trust began working with social care in the 1990s when it was called “jointness” as opposed to “integration”.

“At the moment it really feels like there really is a social movement happening, and that there is a policy popped on top,” she said. “I’m slightly bothered by having just these two models,” she said. “The form should follow the function.”

However, on a positive note, she said: “It is the first time that you are actually hearing primary care and mental health actually talked about at senior level and it’s not being entirely acute dominated. The reason that things haven’t joined up before is because I think that primary care and mental health are the glue to make some of the other pieces work better.”

Cormac Tobin, managing director of Celesio, the parent company of LloydsPharmacy, emphasised that technology would have a vital role in determining the success of the vanguards. It was vital to have robust information and fast communication systems to enable the vanguard areas to function, and to monitor and control them, he said.

Technology revolution

He acknowledged that patients’ expectations had changed, meaning they were ready for a technical revolution in healthcare and this could also ease the pressures on a limited workforce.

So, Mr McLellan asked, what was happening on the ground already?

In Birmingham there had been a widely held assumption that University Hospitals Birmingham Foundation Trust (UHB) would want to pick up the PACS model and dominate the market, said Dr Barbara King, a GP in Northfields, Birmingham, and clinical accountable officer for Birmingham Cross City CCG.

However, against expectations, UHB had seen it as an opportunity to work more closely with general practice in a collaborative way. “At the moment they’re not taking the approach of looking to move right out into the market to take over the general practices and set up their own primary care system.”

The workforce had been squeezed in both primary care and the acute sector, said Dr King. There were also increasing patient demands for urgent care on UHB and that had impacted on the trust’s tertiary work.

‘Patients were ready for a technical revolution in healthcare’

“Anything they can do in partnership and collaboration to manage patients better in the community is to their benefit,” she said.

Sally Morris, chief executive of South Essex Partnership University Foundation Trust, said that it had had integration discussions with CCGs, local authorities and some acute providers and that the biggest challenge was linking with GPs in primary care.

“Everybody recognises that to work we need to have the primary care absolutely signed up and involved,” she said. “I’m really jealous of the people saying that they’ve got good primary care involvement.”

South Essex Partnership had been involved in a number of vanguard applications but had not got through the first round. The integration work would go on in spite of that, Ms Morris said. “It’s the only way we’re going to move forward.”

Chris Gordon, chief operating officer at Southern Health Foundation Trust in Hampshire, said: “If we’re not a vanguard we are going to do this anyway. Finally we have found a language, a terminology that we can use that brings the different parts of the health system together,” he said.

“It’s speaking a language that we all understand, a currency that we can share, that’s where the opportunities lie.”

Fiona Edwards, chief executive of Surrey and Borders Partnership Foundation Trust said that, in terms of mental health, the trust worked in partnership with the person who used the service, but increasingly it would be delivering supportive education to partnership organisations. “We have people already in schools educating teachers around behaviour,” she said, so that mental health issues were spotted sooner to enable early intervention.

But getting staff to shift from caring for an individual to a “public health ethos” and having the confidence to share their expertise with other services would take real work.

Integrating pharmacy

One aspect that is often talked about is how to better integrate with and make use of pharmacists in primary care, said Mr McLellan. He asked attendees whether we were finally going to get a system where the pharmacy sector was treated as an integral part of local healthcare delivery team.

Professor Rob Darracott, chief executive of Pharmacy Voice, said the system needed time. He suggested leaving things alone to develop for long enough so bits of the system that might not be centre stage could get engaged. “There were some encouraging signs that finally some PCTs ‘got’ pharmacy, then we got rid of them all and we started again. We had a whole new set of structures where we had a whole range of arguments from my sector about how do we get engaged with that, we’re not included.”

With more than 438 million patient visits per year to community pharmacies, pharmacy was well placed to be involved in prevention, he said.

Mr Tobin said that the main focus of Celesio’s business was moving stock from manufacturer to distributor to pharmacy and finally to patients but the company expected this to evolve as the role of pharmacy changed.

‘With this change would come a huge responsibility’

Mr Tobin said that he expected the company to move towards greater service provision as a partner of the NHS. He acknowledged that, with this change, would come a huge responsibility and the need to keep a patient-centred approach while new ways of working were established.

To prepare for this, Celesio was running pharmacy-led innovation pilots across the NHS to establish new ways of integrating pharmacy into care.

Considering the healthcare landscape as a whole, Mr Tobin emphasised the need for vanguards to set clear timescales for progress, with clear performance indicators. Crucially, any doubters must be overcome, he said, to ensure that pharmacies working in collaboration with other providers were fully on board.

Wider workforce

The right workforce was the secret to making the new care models a success, Mr McLellan said. He asked attendees what they expected their workforce to look like in five years.

The consensus was that there would be a more generalist workforce, but specialist input into community. GP practices would become larger, and the workforce would widen to incorporate patients, their families, the community and volunteers.

Dr McNeil of Cambridge University Hospitals Foundation Trust said that, given his was a specialist academic trust, he expected more focus on that and on a more specialist workforce. “We will have been able to reduce demand for the less specialised services, we will have faster pathways of care to get people back out into the community,” he said.

He expected that the specialist workforce would be working in both the hospital setting and within the community.

Mr McLellan asked whether the trust would still be the employer. Dr McNeil replied: “My personal view is that if we have a system, we should have one budget and people are employed by the system.”

Alastair Henderson warned vanguard areas not to go straight into employment contracting. “If you do want to derail things, try renegotiating or moving everybody to local contracts,” he said. “It will divert attention.”

‘Staff would go into the community for a few days to support community services’

Southern Health Foundation Trust was looking at keeping some unwell patients normally admitted to hospital at home, said Mr Gordon. Staff would go into the community for a few days to support community services. If that happened, every member in those wider teams would be working to the top of their capabilities, he said.

Dr Roper said he expected many more health workers to be trained locally. “I think workforce planning is still on too big a footprint. There’ll be much more local workforce planning in the regions.” Organisations would also need to develop some of their own workforce to meet their needs because they would not find staff with the required skills anywhere else, he said.

To cope with a blending of professions, Ms Wallace said, training would need to become increasingly generic with competency models. “We’ve not got time for everyone to be dual trained in everything,” she said.

“What we really need is to be focused on the competencies that need to be built on top of what people already have.”

“Some medical schools still train doctors in the way I was trained 25 years ago,” Sir Sam said, but a more inclusive approach across disciplines to produce generalists was needed.

There also needed to be “parity of esteem in academia”, he said. “Look at actually how many professors of general practice there are compared to the acute sector and you realise it is a serious issue.”

New roles

As well as roles changing, there would be new posts, such as physician associates, in secondary and primary care, Sir Sam said, and healthcare coordinators who were local people knowing the system. In this challenged environment, patients, their families, the communities they live in and the voluntary sector would need to be seen as part of the workforce, he said.

Social prescribing by GPs to the voluntary sector was absolutely critical, he added: “We have got social prescribing around Bromley-by-Bow. You can prescribe to the health trainers, legal advisers or job creators,” he explained.

His practice’s work with young people also showed how they existed in a different world of instant access to everything, and wanted Skype consultations and clinics at a time and place to suit them, he said.

Andrew Willetts, public sector and healthcare services director at Celesio, said vanguard success would depend on the financial model. Was it short term financial gain or long term outcomes being targeted?

“Look at some experiences in the Hospital Corporation of America market. Some early vanguards there failed because they just looked at it as a short term gain, it was not about longer term outcomes,” he said. “It will be fascinating to see how that comes out in the next few years.”

Sam Jones said she was struck by the point of needing to be employed by a system rather than an organisation in order to feel engaged by that system.

She also said there was a way to go in improving “cross fertilisation” - or the communication and sharing of ideas - across service sectors, which would be vital to the success of the vanguard areas.

Ms Jones agreed with other panel members that patients needed to be seen as part of the workforce and that technology was an issue: children now communicated in a completely different language. If these issues were not taken into account in workforce training and patient pathways, there was a danger the system would end with a workforce trained to provide a service for the past rather than the future, she warned.

Topics

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges

- Alastair Henderson

- CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS NHS FOUNDATION TRUST

- CAMDEN AND ISLINGTON NHS FOUNDATION TRUST

- Community services

- East of England

- HULL AND EAST YORKSHIRE HOSPITALS NHS TRUST

- Integrated care

- London

- Mental health

- NHS Birmingham and Solihull CCG

- NHS Hull CCG

- NHS Tower Hamlets CCG

- North East

- NORTHUMBRIA HEALTHCARE NHS FOUNDATION TRUST

- Pharma

- Primary care

- REGIONS

- Social care

- SOUTH ESSEX PARTNERSHIP NHS TRUST

- SOUTHERN HEALTH NHS FOUNDATION TRUST

- Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

- West Midlands

- Workforce

- Yorkshire and the Humber

No comments yet