HSJ’s 25 Rising Stars will be at the core of the networks that will make NHS transformation happen. What are their prescriptions for making radical change a reality? Claire Read reports

As 2013 drew to a close and a new year dawned, HSJ named its first ever collection of Rising Stars – 25 individuals judged to be the healthcare influencers of today and the healthcare leaders of tomorrow.

In March, many came together at a special seminar, joined by a number of today’s senior leaders. The overarching theme on the agenda was one of the most critical in today’s NHS: driving change.

Opening the seminar, HSJ deputy editor Emma Maier suggested there could hardly be a better time for such a discussion. “It feels particularly fitting to hold this event now, a few days after the budget and a few days before Simon Stevens begins his new role as chief executive of NHS England,” argued the chair for the day’s proceedings.

“In changing times, all organisations rely on rising stars to bring new perspectives, new approaches, and make new decisions - to challenge and change traditional attitudes and approaches.”

It was a theme echoed by Cormac Tobin, managing director at event partner Celesio UK, whose presentation opened the event. He drew comparisons between his own company and the NHS, arguing it is vital in any organisation to bring the approaches of new leaders to the forefront.

“A year and a half ago, we realised we weren’t future proofed as an organisation,” he explained.

‘It feels particularly fitting to hold this event as Simon Stevens begins his new role as chief executive of NHS England’

“Driving change is fundamental to what we do, and driving a lot of change in our organisation was youth; new ways of thinking, people who didn’t suffer from yesterday’s experiences. The notion that how things were done in the past was how they should be done in the future was not held by our young leaders.”

The case study presentations from HSJ’s Rising Stars suggested this is similarly true in healthcare: a new generation is driving change because it is not willing to simply accept the way things have been done before. It was a point perhaps most powerfully illustrated in a speech from Helene Donnelly.

She explained how a refusal to accept what had become regarded as conventional practice led her to become a whistleblower of the biggest NHS scandal of recent years - and then a driver of cultural change in another organisation.

“I qualified in 2002 and very soon after I went to work at Stafford Hospital,” she told delegates. “I settled in A&E and I became immediately concerned by what I was seeing; by the behaviour of staff and the treatment of patients. It got to the point that I started to write formal statements.”

Her concerns were largely ignored by managers, driving her to leave the trust and take up a nurse practitioner role at Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Partnership Trust. She says it was when the chief executive of the organisation saw her speaking on television about the problems at her previous trust that a unique role as ambassador for cultural change developed.

“Having seen me on BBC Breakfast one morning, my current chief executive realised I actually worked for him and that perhaps he should have a chat with me,” she joked. “He invited me in and we had a two hour conversation.

“He said: ‘I’ve got an idea; I like to think we haven’t got a problem in our trust in terms of raising concerns, but I’m not naive enough to think there won’t be pockets [where there are challenges in doing so] so we need to make sure staff can raise concerns - would you take on a role to encourage and promote that?’

“So we developed the role of ambassador for cultural change. And it really is a culture thing. It encompasses patient safety but it’s about making sure people are accountable and that staff are educated in terms of raising concerns. We didn’t just want it to be defined in terms of raising concerns,” explained Ms Donnelly.

Data shows that, as well as having an impact on patient care, Ms Donnelly’s role is leading to cost savings for her organisation. “Having me in post has directly reduced staff sickness resulting from stress. So we’re saving money in terms of that. And we have been able to avoid disciplinary processes and hearings because we get involved in issues at early stage so they don’t escalate, again saving money.”

Unsurprisingly, the issue of cost savings and patient care improvements was touched on by many speakers: it is, after all, the reason that the NHS so desperately needs the sort of changes its young leaders are driving.

ebastian Yuen, a consultant paediatrician at George Eliot Hospital Trust and another of HSJ’s first Rising Stars, argued that it was an important way that everyone working in healthcare was united.

“We all face pressures and we are all trying to understand what we need to do now,” he argued. “There are great challenges now around money; the need to do more with less. We are all connected [to that].

‘Somebody who is happy to give you your information is likely to be someone ready to work collaboratively with you’

“I think the NHS really needs transformational change,” he continued. “I spend a lot of time in networks and inspiring people inside and outside healthcare, and there’s a sense that there’s an enormous pressure coming.

“We have to radically improve processes and pathways and networks - but none of this is enough. The key to making the change we need is the cultural change which Helene has spoken about.”

In the same way as Ms Donnelly, Dr Yuen outlined how his personal experiences had driven the desire for that change.

“My mother came from Ireland,” he explained, “and ran away from a well to do family to become an art student. My father came from China - his family escaped the Mao revolution. It was a tough upbringing - we were homeless and then moved into a derelict council house - and my father’s idea of discipline came from China.

My brother said we had a bad life; I said I would work my socks off to do something better and different. At school I was called a disruptive influence,” he added with a wry grin.

“At the time I was upset by that. I’m quite proud of it now.”

He explained how he chose to become a doctor but how his first application to medical school was rejected.

“So I became a healthcare care assistant for a year. I remember consultants and medical teams walking around, and the patients just passively receiving care. That stayed with me: I felt it was really important to help people understand what was going on.

“If we have problems in healthcare, we created that system, we need to own that and change that,” he argued. “We need to learn how to lead change across NHS.”

Dr Yuen said his own education in that area had come largely from the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, where he was a fellow. “It was there I learnt how to lead process improvement,” he said.

“I also learnt a lot about me - and I learnt I had to learn to listen. Halfway through my fellowship, they had a big meeting to decide whether to kick me off because I hadn’t yet achieved anything. What I had to do was to go back, and to learn to listen.

“My project involved developing a way to better spot when sick children deteriorate,” he continued. “I went to lots of hospitals with good paediatric early warning score forms [early warning scores are calculated from data based on vital signs observations, and provide a good indication of how unwell a patient is]. But the patient died because the staff didn’t trust the form. So [I learnt] how to engage people to use and believe in tools.

“I listened to teams, listened to human factors experts, and we reduced crash calls on the paediatric ward from one a month to one in nine months.”

It was a story which spoke to the power of networks in driving change, a theme explored in depth by three other HSJ Rising Stars: Pollyanna Jones, operational manager at King’s College Foundation Trust; Jeremy Tong, a specialist trainee in paediatric intensive care at Birmingham Children’s Hospital Foundation Trust; and Damian Roland, NIHR research fellow in paediatric emergency medicine at the University of Leicester.

Building connections

Each has been heavily involved in NHS Change Day, the frontline-led movement to improve health and care.

Now in its second year, it is an initiative which has garnered widespread attention - not least since, as a social media-led movement, it is seen as a groundbreaking example of the power of new methods of building connections.

“We asked people to come together and say what they were going to do to make a change and a difference for patients, and then to report back on what they had done,” explained Ms Jones. “Change Day is not just about talking. It is about doing something different. But it’s also about creating networks, learning about leadership in a new way, and learning about how to do things differently.”

“We’ve had a lot of success with Change Day,” continued Dr Tong. “We have had half a million pledges - and 1.3m work for the NHS. Of course, some people have made more than one pledge, but it’s still a pledge for every two to three people in the health service.”

The extent to which NHS Change Day has captured attention is impressive and undeniable. Arguably even more interesting, however, was when the three presenters spoke of some of the criticisms they had encountered during the second year of the movement: not least the suggestion that it was not actually talking about change.

“About two weeks before this year’s Change Day, we started getting constructive criticism,” reported Dr Roland. “People were saying that these are pledges saying I’m going to give great care today, and that is frankly ridiculous because you’re pledging things which are the very construct of healthcare itself.

‘Can you keep the language you have now and be very different leaders when you get to the top’

“It was a reasonable challenge and in order to counter it I wrote a blog explaining my experience that during a very busy shift I had forgotten to introduce myself to some patients. I was ashamed, and wrote a blog about it arguing that if you are going to criticise you need to be 100 per cent confident that what you are doing is right 100 per cent of the time.

“For me, Change Day has been transformative. It met an unmet need: people wanting to voice some of the concerns that Francis and Berwick have made publicly acceptable to voice. It has taught me a lot about leadership and about networks.”

Dr Tong agreed. “We used to talk about hub and spokes networks, people telling people what to do,” he said. “But that is not going to work anymore. I believe the future is networks and nodes. Nodes have the same power as a network, the network are the facilitators.

“This is where the power of Change Day comes in - everyone’s equal. It’s about bringing everyone together who has done Change Day and giving them a methodology. They already had the ideas [of change], they know what’s wrong, so give them the tools to make that action happen. Just imagine what that could do.

Rise of the connectors

“I believe the leaders of the future are going to be the connectors,” he continued. “The people who bring networks together.”

And while social media might be a powerful way of making connections, those behind Change Day say they are learning it cannot be the home of a genuine network.

“We are in an electronic [world] now and words like network, collaboration, communication, communities and friendships have different meanings,” suggested Dr Roland.

“But you don’t get networks through LinkedIn, communication through Twitter, and a friend is not just someone whose Facebook wall you check. When you think about networks you have to think about individuals, and touch those individuals with stories.

“Change Day itself is about people making their own individual stories. I often think about the narrative I give, the stories I tell, and I know many people in this room here today who have their own personal narrative.

“But I wonder if our networks are aligned to that story. Is the story you have the same as your network’s, and are those networks’ stories cross-transferable?

“If I want to disseminate a story, it’s not as simple as sending it to Dr Yuen and asking him to distribute it to his network. Because the story that comes to me may be different to the one that goes out via Sebastian. We can’t just rely on the electronic networks on which we seem to have become so dependent.”

“We have learnt about engagement, about showing people what they can do, allowed them to say it’s possible to change if they want to - even in this environment, in this climate,” continued Dr Tong.

“That’s important because I think the NHS has lost a bit of its self confidence in the last few years with the pressure it has been under and the media scandals.”

Amir Hannan, another of HSJ’s Rising Stars who spoke during the event, had particular experience of facing the media spotlight.

In 2000, as a newly qualified doctor, he took a job at 21 Market Street - the GP practice previously run by Harold Shipman. “Patients were saying: ‘How can I trust you? How can I know you’re not Shipman?’” he told delegates.

It was an experience which led to a revelation. “I began to realise that the patient in front of me is the expert,” said Dr Hannan.

“It is the patient who knows about their symptoms and how those symptoms are affecting them, their family, their workplace.”

This has led Dr Hannan to drive for a major change: giving patients access to their medical records. The power of such a move was illustrated by his co-presenter Ingrid Brindle, chair of the patient participation group at his current GP practice.

She explained how, since 2006, she has had full electronic access to her GP records. “Just think how powerful that is,” she urged delegates.

“I can access all my GP information from anywhere in the world at any time using three passwords that are in my head and all I need is access to a computer or I can use my mobile. If I’m taken ill, all the information is available for people who need to help.”

She had come up with the term “empowerlution” for the change she felt the NHS needed - not evolution, not revolution, but empowering patients, clinicians and managers to make a change.

“Somebody who is happy to give you your information is likely to be someone ready to work collaboratively with you,” she suggested.

“If I turn my computer screen around so the patient can see the same information I’ve got, then we move to a very exciting a place - a partnership of trust between patient, clinician and computer,” Dr Hannan said, adding to the idea.

But he pointed out that the irony that, while demanding change, the current environment can also threaten to stifle it.

“[Young people] come in to healthcare with bright new ideas and yet it can feel really scary - like a gun is being pointed us, and we’re being told you’re not doing this, you’re not doing that.”

It was a theme expanded on in the keynote address of the day, given by Dr Keith McNeil. The chief executive of Cambridge University Hospitals Foundation Trust argued that bravery is crucial to change.

“Innovation is thrown around as a word, but what does it actually mean? It’s not about doing the same old, same old day in day out, harder and harder wishing something would change. It’s about using our intelligence to do something different.

“And that is partly about courage; having the courage to try things and fail. As rising leaders, you have to be prepared to put your head above the parapet and say this is not right - and then do something different.

Importance of courage

“We would be nowhere in medicine if people didn’t have the courage to change,” he reminded the audience. “The people who did the first heart transplants were labelled as murderers on the cover of Life magazine.”

And he argued that, with increasing demand and decreasing resources, there was no time to lose. “We can’t afford to wait. We have to start right here, right now,” Dr McNeil said.

“We can no longer afford to work at the speed of government - it’s too slow. We have to change the mindset when it comes to seizing opportunities: we can no longer take six to 12 months to take decisions; we have to be flexible and agile to take opportunities.”

The key question, then: how do we do that? How can we enable change and encourage flexibility and bravery? Moving away from command and control would be a good start, Dr McNeil suggested.

“Command and control systems stifle innovation, prevent engagement, and grow and grow and grow because each time a command is sent out it has unintended consequences,” he suggested.

“We currently have a system designed to deliver exactly what we get, and we have got to change that mindset to do it differently.

Sebastian Yuen on a new generation

We are entering a period where the pace of change is becoming exponential and a new social era is emerging. This is a world without hierarchy and where influence comes through your connections. Small, agile companies can change their core strategy rapidly to take advantage of new opportunities. Permission to fail is the first rule of innovation. Participation by everyone is key.

For these reasons, we need a new group of leaders. People who look out, not in or up; who are open and collaborate; who are comfortable with the messiness of life and continuous change; who learn from failure. An understanding of communication, particularly social media, data and how to build communities and social movements are important skills.

These leaders will not revert to command and control as there may not be large organisations to command and control. The question is: will the NHS evolve quickly enough to keep the Rising Stars? Will the climate they need to thrive only be offered by third sector or private companies?

Sebastian Yuen is a consultant paediatrician at George Eliot Hospital Trust, Nuneaton

“We have got to create the right environment for people to flourish. We’ve got fantastic people right across the NHS and we do everything we can to shut them up and bury them away rather than let them flourish.”

He was particularly keen to see greater clinician involvement in change.

“21st century healthcare should focus on effectiveness and productivity and outcomes, and clinician engagement is critical to this. If they are not engaged in delivering high quality care, we will get nowhere.

“In most businesses, the brains trust sits in the offices and the worker bees are on production line. But in health, the brains trust is at the coalface - performing the operations. That is a very different paradigm to most businesses. The clinicians are the rocket scientists out there doing the work.”

The day’s event, and the Rising Stars list in general, clearly showcased some young clinicians getting keenly involved in driving change. But one of the more experienced leaders present on the day posed an interesting question - would that last?

“It’s been a brilliant set of presentations,” said former chief executive of the NHS Confederation Mike Farrar during a question and answer session.

“But I have a question for anyone who’s presented. Earlier this week I was at a meeting of the Shelford Group [the informal network which brings together 10 of the most powerful English NHS trusts] and that group speaks about structures and money but has an entirely different way of framing the situation.

“Is there an inevitability that by the time the people who have presented today are chief executives, you will speak about structures, acquisitions and managing change in a very different way?” he asked. “Or can you keep the language you have now and be very different leaders when you get to the top?” In other words, perhaps, does the new generation not in fact represent change but simply youth?

It was a question which continued to be pondered after the event (see Sebastian Yuen’s article, below) but it was also addressed on the day.

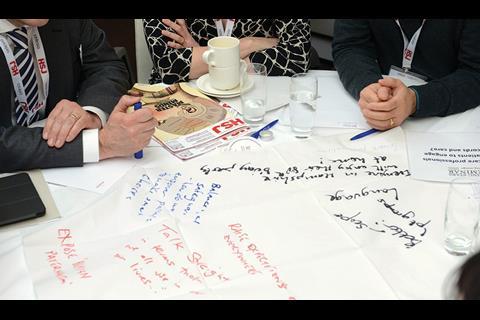

During an interactive “world cafe challenge”, delegates were invited to brainstorm answers to some key questions raised by the day’s presentations.

‘We are in the social media era - it is flat, with no hierarchy’

Eight tables were set up, complete with paper tablecloths on which thoughts could be scribbled. One of the questions: is the new generation really different? Yes, suggested some.

“We are in the social media era - it is flat, with no hierarchy.”

True, perhaps, but do organisations and attitudes yet reflect that? Possibly not.

“The blame culture - both internally and from external sources like the media - is a challenge,” said one group when considering whether the new generation would ultimately conform to more traditional models of leadership.

“We need to change performance management to reward discussion of and learning from ‘failure’ as well as ‘success’. Transformational change involves innovation, involves risk - we have to be willing to take risks and fail.”

Delegates had little doubt such change was needed, however.

It was striking that, when asked to describe the sort of leaders the NHS would need in five years’ time, the words they used could equally have been employed to describe HSJ’s Rising Stars - and particularly those Rising Stars who spoke at the event: strong values, embraces patients, intolerant of hierarchy, listens, goes above and beyond, holds people to account in both directions, enables others to achieve, purpose, passion, humility, courage.

Summing up the day’s proceedings, and drawing on discussions during her own participation in the world cafe challenge, Emma Maier suggested there were lessons for both existing and younger leaders.

“On the part of those already in senior leadership roles, they need to recognise the need for change and empower new generations to take calculated risks,” she said.

“And for the new generation of leaders, there are two words that rise to the top above all others: resilience and integrity; the idea that they can carry on challenging and pushing back against existing ways of doing things.”

Generation Why – HSJ Rising Stars Supplement

The new leaders questioning how the NHS works

- 1

- 2

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Rising Stars seminar: Change Directions

No comments yet