With specialised commissioning undergoing a major restructure in recent years, prompting a period of transition for planning, commissioners in Cheshire and Merseyside turned to the Cardiac Network. By Juliette Kumar and Claire James

NHS England has set out a vision for a clinically led system for commissioning, with specialised commissioning that is nationally planned and locally responsive. Over the last two years, specialised commissioning has undergone a major restructure and has been in a period of transition. As a result, specialised commissioners have been reluctant to leave planning legacy issues for the new NHS England.

Conversely, they also acknowledged that a planning blight in some services might realise undesirable consequences as district general hospitals press ahead with local plans, going “at risk” with a “build it and they will come” approach to the development of services.

Realising that a “do nothing” option would result in services developing ad hoc, and that any strategic changes to services would have more credence with the backing of the clinical consultant community across the region, specialised commissioners asked the local Cardiac Network if they would facilitate the development of an agreed clinical model for the region.

Innovation alert

- The new HSJ innovation and efficiency email alert sends the latest innovation news and best practice resources straight to your inbox every Thursday. Find out more.

The Cardiac Network is one of the strategic clinical networks. Its role is to provide the voice of the clinician, engage the cardiac community, agree and define best practice clinical models of care within the context of strategic priorities and to realise the benefit of network relationships in implementing quality improvements.

‘Strong, credible, clinical leadership is essential in leading the process of consensus on key strategic planning’

The Cheshire and Merseyside Cardiac Network covers a large geographical area, and includes seven district general hospitals and one tertiary hospital. The network had already established local district general hospital aspirations for the development of complex device implanting and follow-up services during a previous review.

These aspirations presented a challenge to the existing tertiary-centric model of care and posed the question: should the network support the devolvement of complex cardiac devices implanting and follow-up services to district general hospitals, or continue with a centralised tertiary model of care?

Complex procedures

Complex cardiac device procedures are relatively low-volume and are high-cost healthcare interventions that benefit patients with abnormal heart rhythms. As such, commissioning for these services falls under specialised commissioning functions.

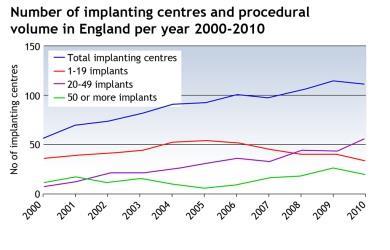

Historically, these services have emerged largely as a result of local enthusiasm. As a result, the last decade has seen a significant increase in the number of device implanting centres, doubling from 58 in 2000 to 114 in 2010.

In some areas across the country, devolvement has failed to provide or sustain the recommended minimum volumes of procedures required to maintain competencies for patient safety, with almost a third of centres failing to meet Heart Rhythm UK’s minimum standards, set at 10 per operator and 20 per centre (see graph below).

In January 2013, Heart Rhythm UK updated standards for implanting complex cardiac devices and recommended that new implanting centres achieved a minimum of 30 procedures per operator, requiring 60 per centre. The situation presents a challenge for commissioners nationally as there will be an expectation that established services begin to move towards the higher figures, so they can develop services that achieve best practice minimal procedural volume for maintenance of clinical competencies.

Intervention

The Cardiac Network was aware of the national picture in relation to the development of implanting centres and difficulties in maintaining procedural volume, and wanted to set out a robust strategy that provided assurance that procedural volume could be achieved and maintained.

To achieve this, the network set out and led a process of consensus development for the strategic planning of complex cardiac device services. This included a number of steps and a priority was the meaningful engagement of the consultant community, which at the outset held polarised views on the best direction of travel for CCD services. Steps included:

Stakeholder engagement

The process of engagement involved semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders including consultants, patients, managers and cardiac physiologists, a stakeholder event and facilitated workshop.

The stakeholder engagement process identified an initial mistrust of the process of strategy development. It acknowledged that current services are safe and of high quality but there was fragmentation within the pathway. It also acknowledged that the management of unscheduled care for patients could be improved and that patients valued care close to home, wherever possible.

Regional service review

A root and branch service review identified the local and national performance of implanting services, a deep understanding of the performance of the current service model, a review of patient satisfaction measures, impact on training for both cardiology trainees and cardiac physiologists and an understanding of the management of unscheduled patients.

Data and literature review

Current standards and guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the professional bodies were examined and services were benchmarked against national audit data on complex cardiac device procedures. A literature review identified the association between higher procedural volume and low complications, as well as an acknowledgement of a lack of systematic strategic planning and evaluation of these services nationally and the potential impact this could have on implantation rates.

Local device expert panel

A local device expert panel was convened that included device experts from each of the trusts within the region. This group identified a shortlist of model options for complex cardiac device implanting and follow-up services. In the absence of consensus at this local meeting, it was agreed that the final decision on consensus and recommendations be deferred to an external expert panel.

External expert panel

An external expert panel was set up, tasked with achieving consensus and providing final recommendations for a complex cardiac device implanting and follow-up service model for the region. Panel members included device specialists from outside the region, a GP representative, patient representative, a commissioning representative, district general hospital representatives and a cardiac physiologist representative.

Consensus development

The process of consensus development was approached during the expert panel meeting by using both iterative discussions and a review of options against agreed criteria.

‘Stakeholder engagement is key and necessary for strategy development’

An appraisal scoring tool had been developed; however, it was important for the panel that the process was not completely dominated by a solely deductive/rationalist approach. It was felt that such an approach would not be able to take into consideration some of the drivers for change that included more subjective elements of benefit. For example, access to care closer to home and the “halo effect” or benefit on the whole organisation of having a local clinical expert to champion services.

This led to a full consensus to devolve follow-up services to trusts able to demonstrate clinical competency, skills and a commitment to quality of care for patients. Full consensus was also achieved to devolve to one other trust that was geographically positioned. The panel agreed that strategy should be seen as the start of an evolutionary process of service model change that would be reviewed and monitored closely by the network.

Reflection and learning

The process of strategy development provided an opportunity for a comprehensive service model review and highlighted a number of issues in relation to the delivery of services for complex cardiac devices implanting and follow-up, and that will form the basis of quality improvement projects.

Strong, credible, clinical leadership is essential in leading the process of consensus on key strategic planning. The clinical lead does not necessarily need to be a subject expert but does need good leadership skills for engaging, constructively challenging, communicating, sharing a vision and managing conflict and relationships that are unproductive.

Stakeholder engagement is key and necessary for strategy development. Providing consultants, clinicians and patients with the opportunity to give their perspective and views enables meaningful debate and a better understanding of valid concerns.

Juliette Kumar is director at Improvement by Design; Claire James is senior service specialist at Cheshire, Warrington and Wirral Area Team, NHS England

Appendix

Table 1. Key drivers for change

| Key drivers | Description | |

| 1 | Fragmented care | It was perceived that patients would have better continuity of care if managed closer to home, and better access to unscheduled care. |

| 2 | Unscheduled care | Patients with unscheduled care episodes are compromised with limited access to device expertise at local district hospitals. |

| 3 | The “halo effect” (the effect on the trust of having in-house expertise) | Trusts are unable to benefit from the formal and informal enhancement of knowledge and education that is associated with a local expert and champion for device services. |

| 4 | Opportunities for better services for patients | There was a perception that there were opportunities to develop, improve, innovate and advance the quality of service provision for patients across the region. |

| 5 | Attracting talent to districts | The specialised focus of the training has meant that new consultants naturally seek work in hospitals that enable them to use and maintain competencies and skills gained. District general hospital report increasing difficulty in attracting consultants with specialist training to districts. |

| 6 | Financial impact | District hospitals seek to increase income and maintain viability in a healthcare market economy. |

Table 2. Agreed principles of service delivery

| Key principles | Description | |

| 1 | Critical mass of patients* | Model is able to maintain a critical mass of patients. This is paramount for developing and maintaining competencies of staff provision of training opportunities for junior staff and re-training consultant staff. Must meet Heart Rhythm UK standards as minimum. |

| 2 | High-quality services* | Model can provide high-quality care. Patient safety and quality of care, predicated on audit results from current permanent pace-making and measured prospectively by a future rolling audit of complex cardiac device clinical outcomes. Must meet Heart Rhythm UK standards as minimum. |

| 3 | Out-of-hours and emergency cover | Model can provide access to 24/7 emergency care with 24/7 on-call consultant rota. Adequate provision for out-of-hours/troubleshooting; end-of-life deactivation; and switch on/off for emergency surgery. |

| 4 | Care close to home | Model provides local access. Patients felt that having care at a local hospital would provide more continuity; improve coordination of hospital appointments; and allow better communication. |

| 5 | Ongoing care | Lifelong follow-up with access to remote services as standard of car. Access to psychology, arrhythmia nurses, heart failure nurses and local patient support groups. |

| 6 | Impact and risk | Model does not adversely destabilise the tertiary service. Development of the service does not significantly impact upon the tertiary centre or its ability to deliver care in other clinical areas. |

* Red flag = model must meet principle; if unable to meet principle then consideration of model will cease.

No comments yet