NHS Virtual Ward models are a necessary solution for today’s challenges and the right investment for the future. The decisions trust and ICB leaders must make today can turn pioneering home care options into permanent operational improvements to the NHS hospital experience

Virtual wards are necessary and visionary

NHS England’s call for a national rollout of 25,000 virtual ward beds is a direct response to the capacity challenges faced by hospitals up and down the country, as the lingering effects of covid, coupled with difficulties many trusts have in discharging medically fit patients, has led to record occupancy levels. The current system simply cannot continue to care for the volume of patients needing acute and chronic care.

Sponsored by

This call to action is also the impetus to innovate. The NHS is embracing a vision for hospitals to invest in digital technology to provide better care to patients in a place they would much rather be, at home.

Virtual wards will not be a quick fix for all of what ails hospitals now, but we believe the NHS is on the right track in its push to turn innovative virtual ward programs into a routine part of NHS service.

Why the spotlight on virtual wards?

The total number of NHS hospital beds in England has halved over the past thirty years, while the number of patients being treated for chronic disease continues to rise. At 2.3 beds per 1,000 persons, the UK’s hospital bed capacity utilisation rate ranks among the lowest in the world—34 out of 37 countries in the OECD’s most recent assessment.

As bed occupancy reaches historic high levels, it is evident that the health service is hitting a tipping point – evidenced perhaps by the drop in productivity the NHS faces in terms of throughput and length of stay. The NHS sees virtual wards – as opposed to growing physical bed base – as the right step for delivering care in the future.

Whilst the concept for virtual wards, and digital technology applications in the patient journey, was seeded in the mid-2000s, it has been only in the last two years that NHSE has encouraged a rapid expansion of virtual ward capacity, with ambitious plans to deliver 50 virtual beds per 100k population.

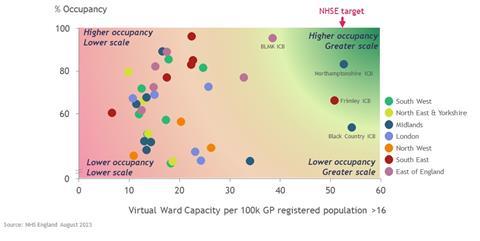

So, where do we find ourselves today? As of August 2023, there were nearly 10,000 virtual beds in England – a world-leading effort – with an impressive pace of adoption: between March 2023 and August 2023, the NHS was adding nearly 14 new virtual ward beds per day.

However, the NHS has struggled with consistent implementation: the rate of deployment has been variable across the country, and occupancy – a good metric to measure the clinical acceptance of the model – has remained stubbornly low at or below 65 per cent.

There are success stories: Northamptonshire has built its virtual ward programme over a number of years, with trusts working in partnership with Doccla since 2020 to both prevent admission and speed discharge. Norfolk and Norwich Universities Hospitals Foundation Trust have also demonstrated the potential to operate an acute virtual ward model at scale, with a model that covers 15 pathways across specialties such as respiratory, stroke, and cardiology, and with ambitious plans to continue to scale further.

However, part of the difficulty facing many integrated care boards and hospitals is that they do not have the experience yet to know which model is optimal. NHSE have shared case examples and guidance, but it can be difficult to navigate the different model choices to know what can work at scale, and in particular, it can prove particularly challenging to get clinicians to accept and use virtual wards.

What are the models of virtual wards?

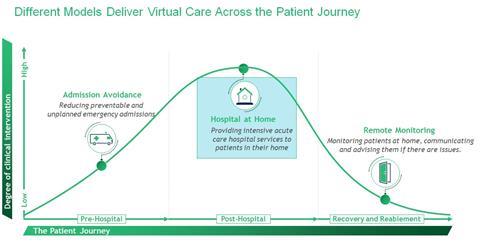

The term, virtual ward, has become a catchall phrase to describe a range of technology-enabled remote care for patients. Broadly, these can be categorised into three types:

- Admission avoidance- focusing on patients most at risk for emergency, unplanned, and recurring admissions. Qualification for virtual care is determined by predictive modelling and clinical decisionmakers, including the virtual ward team and the patient’s primary doctor.

- Hospital at home- The core elements of this model are remote monitoring, telehealth or home visits from clinical staff to deliver care, allowing specialist clinicians to frequently check patients, and intervene quickly, if necessary. NHS analysis of hospital admission data suggests that a virtual ward of 50 beds could deliver the equivalent of 31 additional secondary care beds through more effective utilisation of staff.

- Remote monitoring is a component of the Hospital at Home, although it is sometimes a stand-alone model. Remote monitoring conducted by clinicians, patients, or both makes it possible to release a patient who would otherwise need to remain in the hospital.

Based on the review of best practices for most systems, we believe the hospital-at-home model is the best solution to address current and urgent operational challenges. This is because it is easier to identify appropriate candidates who have been admitted and are candidates for shorter stays. In addition, it requires fewer resources to build out than the admission avoidance strategy, which can be followed by more remote monitoring over the medium term.

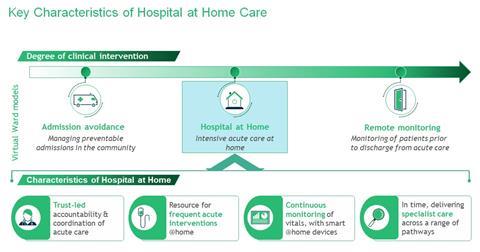

The key elements to implement for a hospital-at-home model are presented in the below exhibit:

- Hospital leadership is responsible for staffing and accountable for processes and results. This is clinically led with consultants maintaining ownership of the patient’s care.

- The model is designed and resourced for frequent acute-level interventions in patients’ homes and equipped for continuous patient monitoring with smart devices.

- At roll-out operators and clinicians work together to identify a limited number of patient pathways to prove the value

- Hospital at Home models deliver specialised care across a wider range of pathways, and with scale, the model can take on even more complex care

Five critical questions for NHS leaders

We have identified several key elements that have been most useful to work through with hospital and integrated care system leaders thinking about how to scale Hospital at Home implementation and ensure high utilisation. These are articulated in the six critical questions below:

1. Who are the right clinicians to engage and champion the right models?

- Executives and operational leads must work closely with supportive, engaged, and innovative clinicians to identify the best patient pathways and solutions to include in an initial rollout.

- Transparency is the most effective way to engage clinicians. This includes sharing consultant-level data on the utilisation of virtual wards and length of stay, at a pathway level.

2. How should we promote wider clinical buy-in and leverage their expertise? Operational leads must focus on designing processes which ease, rather than add to the day-to-day burdens of clinicians in the hospital.

- An effective way to do this is by using virtual ward nurses – who are well-positioned to proactively identify patients who are appropriate candidates for virtual wards and can engage consultants responsible for their care.

3. How can healthcare leaders quickly unlock sufficient Virtual Ward funding?

- Early engagement of all ICS partners helps to position hospital at home at the top of the wider virtual ward funding agenda. Take a pragmatic view to coordinate providers so that incentives are aligned across the pathway and ensure the short-term value for the system is clearly articulated.

- Detailed planning should leverage evidence from studies and learning from other rollouts nationally. This will strengthen virtual ward proposals when they’re evaluated against alternative initiatives vying for funds.

- Performance metrics such as average length of stay, readmission rate admission avoidance, backlog reduction and release of acute bed capacity strengthen use case arguments.

4. What are the ICS partnership opportunities?

- Hospital clinicians should retain governance control to ensure virtual wards reach desired levels of utilisation. However, community providers can lead the delivery of remote monitoring and interventions.

- Articulating the longer-term vision for cross-system virtual care will be key to winning a broad base of support.

5. What are key virtual ward staff-related challenges and opportunities?

- Specialist clinicians should maintain ownership of their patients as they transfer to the virtual ward. This is important to reduce perceived risk and other concerns.

- As the model scales, there must be recognition in job plans to ensure sufficient time to care for patients in a virtual ward.

Virtual care needs to scale; failure is not an option

This is a critical moment: Virtual wards have demonstrated their potential but have not yet scaled up. To deliver on their promise of more sustainable care, that offers improved working conditions for staff, and a better experience for patients, Virtual Wards have to use the right model delivered in the right way. This has proved to be a Gordian knot for many. The answers to the questions we have posed above provide some direction to untie the knot.

Now is the time to work faster and smarter to make virtual wards the norm.

Dr Ben Horner, managing director and partner, Boston Consulting Group

Stephen Sutherland, managing director and partner, Boston Consulting Group

Cassandra Yong, partner, Boston Consulting Group