With previous hospital mergers apparently resulting in few significant improvements in clinical quality or financial performance, Penelope Dash and colleagues consider why hospital consolidation succeeds or fails

Across the developed world, pressure to deliver greater volumes of high-quality care at lower costs is translating into efforts to control, consolidate and reduce clinical activity levels in hospitals.

Consequently, we see an increasing number of hospitals planning to safeguard their clinical and financial viability − in the NHS, across Europe and throughout the US − by merging with other organisations to improve performance, reduce costs and ensure scale.

‘Hospital mergers are not doomed to failure − examples of success can be found’

Unfortunately, examination of the evidence from previous hospital mergers suggests very few have delivered significant improvements in clinical quality or financial performance. We therefore set out to develop a more nuanced understanding of why hospital consolidation succeeds or fails, and what lessons can be derived from history. We shared our thinking with 100 NHS chief executives, chairs and regulators.

Test of time

Of those attending our seminar, no one strongly agreed and only 19 per cent somewhat agreed with the statement “hospital mergers have delivered significant value to the NHS”. In England, 112 hospitals merged between 1997 and 2007.

‘The challenges of a merger should not be underestimated; many hospital mergers fail because of poor execution’

It is not always clear why so many mergers failed to deliver their anticipated benefits. Our research − an examination of more than 700 mergers around the world, combined with surveys, interviews and a literature review − suggested the primary reason was the absence of substantial changes in service delivery.

Delivering major improvements in care quality and productivity requires changes in how services are provided, and there is little evidence that the merged organisations implemented these. Failure to genuinely integrate the organisations also played a part. We have frequently found that, even long after a merger, leadership structures, performance evaluations and incentives continue to focus on individual facilities, not the combined entity.

Nonetheless, hospital mergers are not doomed to failure – examples of success can be found. University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust is the product of the merger of six local hospitals. After considerable service restructuring, it has achieved strong market share in several key specialties and scores highly in national rankings of care quality and patient satisfaction. Other successful examples include Tayside Hospital in Scotland and the Giessen and Marburg University Hospital in Germany. Comparison of successful and unsuccessful mergers suggests two factors maximise the chances of a good outcome:

- Compelling strategic rationale: successful mergers are based on a deep, objective appraisal of the economic and clinical value that could be generated for either the combined institution or the broader health economy through service rationalisation, cost reduction, and new service development.

- Effective pre- and post-merger management: although a compelling strategic rationale is necessary for a success, it is not sufficient on its own. It must be accompanied by sustained focus on how economic and clinical value can be created, as well as by excellent preparation and rigorous execution.

Compelling strategic rationale

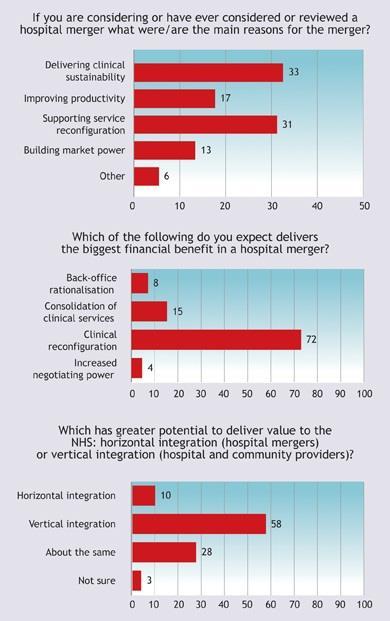

Our research showed that the most-cited rationales for a hospital merger were to improve or sustain clinical quality, reduce operating expenses, increase revenue or reconfigure service delivery. The responses from the seminar attendees reflected these results:

Quality

To overcome clinicians’ resistance and win public support, a successful hospital merger requires a persuasive argument for how both the quality of and access to care will improve. A well-executed merger provides multiple opportunities to enhance patient outcomes. Consolidation, for example, can improve care quality by eliminating subscale service provision, increasing transparency in care quality and/or improving performance management processes so that problems can be more easily identified. Mergers can also enable organisations to invest in new services and/or develop centres of excellence, both of which can provide better access to higher-quality care.

Reduce operating expenses

The most frequently cited financial rationale for hospital mergers is cost reduction via economies of scale. In theory, significant potential to cut hospital expenses exists − about half of hospital costs are indirect. Although most mergers do not reduce costs to anywhere near this potential, hospital chains are often able to increase efficiency and raise operating margins by 2.5-3.0 per cent in acquired facilities. This success is likely to result from a combination of due diligence in hospital selection, experience in managing mergers and the cost benefits of larger scale.

Individual hospitals can still achieve savings if a merger is well executed. Key to this are strong performance management, including adoption of new processes that capture shared benefits, and a focus on standardising and integrating work processes, support functions, suppliers and investments. More radical changes, such as integration of clinical services, can substantially reduce costs. For example, if two UK hospitals (one of which operated two sites) merged, savings would be 1.0-2.5 per cent with no consolidation − but 12-14 per cent with consolidation across sites.

Increase revenue

A merger provides an opportunity to enhance hospital revenue in at least three ways: increased market access; strengthened revenue cycle management processes; and greater market power.

Reconfigure service delivery

The growing mismatch between needed health services and the way service delivery is configured has made it necessary to reduce and consolidate certain hospital-based services. Restructuring service delivery is a major challenge that often encounters substantial stakeholder resistance and political involvement. Hospital mergers can sometimes ease the challenges involved in reconfiguration. For example, trade-offs may be easier to arrange if two sites are in the same organisation.

Seventy-two per cent of seminar attendees believed that the greatest value from a merger comes from reconfiguring services. The majority of attendees also thought that vertical integration had much greater potential to deliver value than horizontal integration did.

Pre- and post-merger management

The challenges of a merger should not be underestimated; many hospital mergers fail because of poor execution. Seminar attendees identified the failure to commit sufficient resources to integration efforts as the single greatest factor in failed mergers.

As well as committing the appropriate resources to the integration programme, we suggest merging organisations follow four simple rules to maximise their chances of success

- Get stakeholders aligned: all key internal and external stakeholders (such as clinicians, commissioners, and regulators) need to support the merger from day one.

- Focus on clinical and economic value creation: understand and quantify the benefits the merger will deliver (both clinical and economic), and then anchor your merger-management approach around capturing those benefits.

- Prepare well: define a comprehensive approach to integration and stick to it, invest in the management team overseeing the integration (mergers are difficult and will require your best people), and do not underestimate the challenge of aligning different organisational cultures.

- Execute rigorously: maintain a tight grip on performance, provide vigorous, high-profile leadership; track integration metrics with the same energy and focus you track hospital-acquired infection rates, cost improvement programmes, and other organisational priorities; and communicate as we have never seen a merger in which the senior team communicated too much.

Conclusion

So, are mergers the answer to the acute problems of the NHS? Well, maybe. The service is facing a whole series of problems that acute sector consolidation and vertical integration could solve. There are undoubtedly big gains in productivity that might be gained from mergers, and there is clear evidence that consolidating the delivery of at least some acute services would improve care quality.

‘The gains on offer require changes in the way services are delivered and, most likely, extensive service reconfiguration’

Greater scale in teaching and research should allow England’s academic health science centres to compete more effectively in an increasingly global marketplace. Vertical mergers between hospitals and community or even primary care providers offer the prospect of genuinely integrated patient pathways, the potential to reduce use of the acute sector and the possibility of lowering fixed costs by consolidating services on to fewer sites (in some cases, making greater use of underused assets).

But we should be realistic about what it will take to realise those benefits. Almost without exception, the gains on offer require changes in the way services are delivered and, most likely, extensive service reconfiguration and site rationalisation.

Service reconfiguration is difficult: it is contentious and inherently political, and takes a long time to deliver benefits. Managers, commissioners and clinicians must be willing to stand behind controversial decisions and invest the resources required to deliver them.

If mergers are to deliver real value to the NHS and to patients, the merging organisations will need to focus on delivering value with a capability and intensity not seen before. In addition, the broader healthcare system will need to ensure that the incentives facing those organisations are strong enough to ensure that the promised benefits are delivered.

Penelope Dash is managing director, David Meredith is a principal associate and Paul White is an external advisor at McKinsey & Company

1 Readers' comment