The mammoth task of sustainably hitting the four-hour emergency care target at North West London Hospitals Trust has required new, stronger relationships between clinicians and managers, as Dena Marshall explains

As we head into winter, many hospitals are beginning to struggle to sustain the emergency care four-hour target. This article describes the journey of transformation that has been taking place at North West London Hospitals over the last two years.

It reminds us that truly transforming emergency care, and sustaining this transformation, is a journey of enquiry.

There is no “magic bullet”. It is about paying attention to the patterns of relating and leadership culture that mobilise, align and direct the passion and energy of healthcare professionals, clinicians and managers alike, who devote vast amounts of their time in service to patients.

‘System problems do not lend themselves to a heroic model of leadership’

North West London is a district general hospital, with some specialist services, operating over two main sites, Northwick Park Hospital and Central Middlesex Hospital. The trust serves a diverse population of 500,000, has an income of £380m and employs 5000 staff.

Dealing with deficit

The health economy has been in financial deficit for many years. Financial stability and the safe and effective delivery of emergency care are the two strategic and operational challenges that the trust has been grappling with since its merger in 1999.

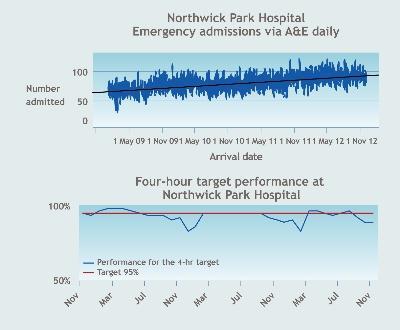

The Northwick Park emergency department is the third busiest in London for ambulance conveyances (See graph one). There are 150,000 combined accident and emergency and urgent care centre attendances and 25,000 emergency admissions to Northwick Park every year. Emergency admissions have increased by over 30 per cent over the last three years. There had been six external reviews of emergency care at Northwick Park from 2005-10, all of which highlighted challenges around leadership and culture as well as resources.

Performance against the A&E four-hour standard was fragile and shored up through short-term investment (see graph two). Repeated attempts to recruit to emergency department consultant posts had been unsuccessful. The physical capacity of the department had not changed since the early 1990s although activity had more than doubled.

Systems thinking

The quality of working relationships within the department and between it and the admitting specialties was poor. There was very little sense of the target to treat or admit patients within four hours of arriving at A&E being owned outside the emergency department.

The emergency department is one part of a system of emergency care. The system also includes acute assessment and admission to/discharge from a hospital ward. Seen in this context, the four-hour target is a measure of how effectively the whole emergency care system is functioning.

In August 2010, following a deterioration in performance, NHS Interim Management and Support’s emergency care intensive support team was invited to visit North West London Hospitals Trust. This visit and the resulting set of recommendations, which pointed to blockages across the whole emergency care system, provided a platform for re-framing this as a whole hospital problem.

Flow

Linked to the concept of systems thinking is ‘system flow’. In this context, flow is defined as the combination of speed and quality (seniority) of clinical decision making. Much of the emphasis of the earlier reviews had been on flow at the “back end” of the hospital, speeding up discharge processes, reducing length of stay and so on.

Our experience has been that while back end flow is important, equally important is flow within the emergency department and within acute assessment.

Repeated observation and mapping of flow across the whole emergency pathway brought attention to the constraints to flow posed by lack of physical capacity to assess and care for patients and lack of senior doctors in both the emergency department and acute assessment unit to make the timely senior clinical decisions.

These observations and mappings of flow, backed up by data, enabled us to make successful cases for both more staff and capital investment required to address these constraints.

Leadership and culture

System problems do not lend themselves to a heroic model of leadership; it is impossible for any one individual, no matter how excellent they may be, to work on all the system wide issues alone. Because the whole system needs to change then leaders, clinical and managerial, are required to work on different problems across the whole system.

The nominated leaders are, in and of itself, not enough. Developing solutions to overcome system problems involves working across wards and departments, facilitating conversations with individuals and teams outside the leader’s direct sphere of control.

‘You need to bring clinicians and managers together, often across the line management structures, to work on shared problems’

Therefore, a collaborative leadership style is required set within a culture of enquiry and learning. You need to bring clinicians and managers together, often across the line management structures, to work on shared problems. For leaders, influencing peers across the system becomes as important a leadership skill as line managing staff in your team.

Following the intensive support team’s intervention, we set up an emergency care programme board, co-chaired by the director of operations and the clinical director for emergency care. This board brought together clinicians and managers from across the entire emergency care pathway to work on problems across the system.

The programme board had oversight for the implementation of our emergency care improvement plan that turned the team’s recommendations into an internal action plan.

Tough choices

In parallel, the operations team embarked on an individual and team development programme aimed at building our collaborative leadership skills. This involved facing some important questions about how we “showed up” as individuals and as a team.

The programme invited an inquiry about the changes that we wished to see in ourselves and in the way that our team worked. As a result of this intervention, two divisional general managers swapped roles without the need for any formal HR process and a deputy director role was agreed from within the team.

These were not easy decisions for the team to navigate. It is evidence of the calibre of individuals and the quality of the relationships within the team that we have been able to work through these issues and come out the other side much stronger as a team.

The trust board was instrumental in modelling the collaborative leadership style that we were expecting to be emulated across the organisation. The chair established a sub-committee that took board level oversight for the implementation of our improvement plan.

Each executive director became a sponsor for the major pillars of our emergency care improvement plan. Executive visibility in ED and across the emergency pathway was increased with each executive director making a regular visit to wards and departments as part of the executive walkabout that was already in place.

Resilience and staying power

Bringing about genuine and sustainable transformational change takes time. It is hugely reliant upon the quality of relationships, and trust, at all levels in the organisation. These sorts of relationships develop over years rather than months. Personal and team resilience and staying power are essential when things get tough and/or do not go accordingly to plan.

At about the same time as we embarked upon the implementation of our emergency care improvement plan, the trust started discussions about merger with Ealing Hospital. It is a real credit to all the clinicians and managers that have been involved in the emergency care transformation that they have carried on championing this work during a period of huge uncertainty.

It has become clear that a strong sense of purpose and a very good sense of humour are prerequisites for leaders embarking on this sort of journey when there is so much external change, outside of your control, happening at the same time.

Out of hospital

Clearly, the system of emergency care extends beyond the hospital. The intensive support team’s review in 2010 highlighted that change needed to happen across the whole health and social care system. As the system has started to see that we are grappling with our internal issues, the focus is starting to shift to include a forensic examination of what is happening outside of hospital as well as inside.

We are not out of the woods yet; overall our performance against the four-hour standard has remained relatively stable over the last two years, which is an achievement in itself given the growth in emergency admissions we have seen over the period.

Underlying the overall position we have seen a marked improvement against a number of other metrics, including ambulance turnaround times. These improvements are testament to all the work we have done around flow. Sustaining performance over winter will be challenging, especially if emergency admissions increase again.

However, we have come a very long way in the last two years. When things get really tough, we will be holding on to all that we have achieved in the last two years and looking forward to our brand new ED department that will open in Autumn 2013.

Dena Marshall is deputy chief executive officer/director of operations at North West London Hospitals Trust.

3 Readers' comments