Boston Consulting Group discusses how an approach that prioritises the engagement of frontline staff, and that leverages three key elements – data transparency, leadership, and empowerment and accountability, can lead to real and sustained improvements in activity, outcomes and staff engagement.

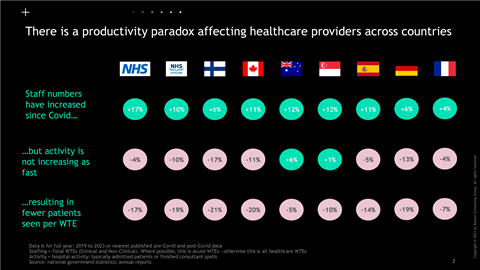

The NHS has seen unprecedented workforce growth, but – in line with many other countries – activity has not risen at the same pace. In a constrained healthcare system, this represents a challenge for the NHS. A challenge that, if poorly approached, risks disempowering staff and entrenching variation in delivery.

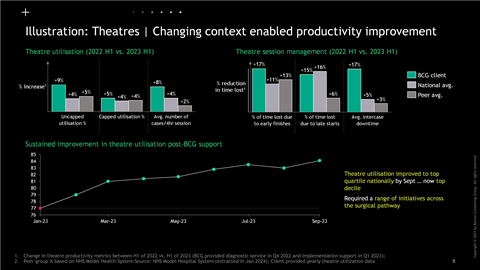

Finding ways to support the workforce to deliver the right activity in the right places is the only way to get to a more sustainable future. This requires an approach that prioritises the engagement of front-line staff, and that leverages three key elements – data transparency, leadership, and empowerment and accountability. Together, we have seen how this can lead to real and sustained improvements in activity, outcomes and staff engagement.

It’s the right time to take a look at workforce

The NHS in England is looking closely at its workforce. After nearly two decades of worrying about workforce shortages, the question that is now being asked is “what should we be asking our staff to do?”, and “have we got staff in the wrong places?”

Provided by

This year’s planning guidance requires every integrated care board area to “conduct a robust workforce establishment review” which includes a reconciliation of staff increases since 2019-20.

And this is right – there has been a notable increase in workforce in the NHS. Between Q3 2019-20 and Q4 2023-24, hospitals have seen an 18 per cent growth in nurses, a 19 per cent growth in doctors, and a 20 per cent growth in managers. But in the same period, those staff are seeing fewer patients in hospital – 2 per cent fewer elective admissions and 3 per cent fewer emergency admissions.

Or, to put it another way, if there were the same ratio of elective and emergency admissions per consultant today as in 2019, the NHS would be seeing more than 2 million additional patients in our hospitals per year.

Squaring the circle – the international picture

And this phenomenon isn’t unique to England. Whilst it is challenging to compare in detail across countries, if you look at healthcare workforce and hospital activity across Europe, North America and Asia, a similar pattern emerges.

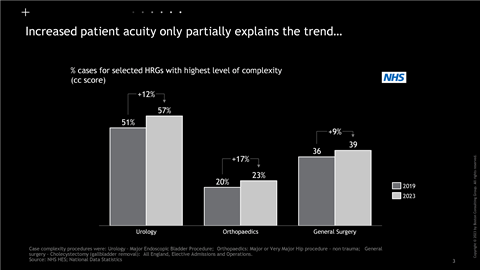

So, what is going on? Certainly, the world of healthcare is different today. Patients are increasingly acute – with accident and emergency departments, for example, dealing with more challenging patients, and surgeries being more complex. Beyond the change in physical needs, mental health challenges, multiple co-morbidities, and an ageing population are all catering to a different experience for healthcare workers.

It’s not all about the complexity of the work. Healthcare delivery itself can be complex – relying on a web of teams, processes and procedures – and so it can be challenging for individual staff members to re-establish pre-covid working patterns. And we should not underestimate the psychological impact that covid and the efforts to recover have had on a workforce.

What is needed is to ensure that we have the right staff, doing the right things in a planned and transparent way. And this is where the NHS has a problem.

How do you solve a problem like the workforce?

In one sense, the answer here should be simple: there needs to be clarity and transparency over what everyone should, and does, do.

For example, for medical staff:

- Every doctor (and allied health professional and advanced nurse practitioner) should have a job plan, that describes how many patients they will see in different settings during their direct clinical care time

- And the sum of the job plans for a given specialty should equal the trust’s annual activity plan for that specialty

- And the sum of trust’s activity plans should equal the ICB plans

- And at any point in the year, it should be clear how every trust, specialty and doctor is delivering against their contracted plans

Transparency and clarity top-to-bottom.

But scratch the surface, and you find that even where this approach ostensibly exists in practice, it cannot solve for two interrelated problems.

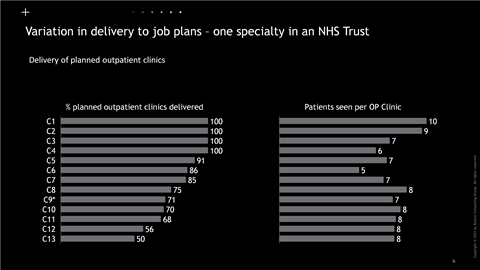

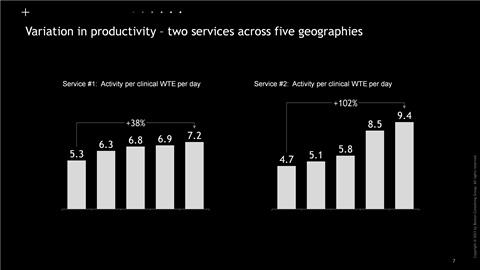

First, there continues to be unwarranted variation – but the magnitude is not always transparent to staff, or the implications clear (eg being able to clear waitlists and make the job feel more sustainable)

Partly, this challenge stems from a lack of definition: there is often no clear view of what activity should be expected of staff. How many patients should a doctor see in an outpatient clinic on average? What should be the throughput for a surgeon in a given specialty? And where will there be planned vs unplanned variation?

It also stems from a lack of transparency in data that can allow staff to have sensible conversations about what they are doing. Too often, this information is not visible, shared or examined.

The second problem is that it is rarely straight-forward for staff to change things to more effectively deliver their role.

For example, if you walk around a trust, time and again you will find that many doctors are not delivering their job plans. This is not necessarily through poor intent, but can be because the plans are not appropriate, or clear. It can also be because NHS organisations can make it incredibly hard for staff to deliver to their plans even if they want to.

Our work with trusts over the past year has shown us that many processes have too much “leakage”. Take outpatients; repeatedly there is a significant gap between the theoretical number of clinics you expect from job plans and the actual delivered number. This can often be attributed to leakage in scheduling – with wide variation within sub-specialties on patients booked per clinic – and in cancellations and did not attend rates. But without taking a de-averaged view it can be impossible to understand where the leakage occurs.

Staff can influence much of this leakage, but too often the prevailing culture disempowers and disengages the frontline. Hospitals are under immense pressure to deliver elective recovery, improve A&E performance, address cancer waits, and find efficiency savings. This often results in a “grip and control” culture that reduces freedoms and bureaucracy at the frontline and disengages the frontline. Behaviour is driven by context – and the NHS can be guilty of failing to give its staff the tools and incentives to help them work out how to be more productive in their roles.

We have used the example of doctors here, but this is the same story with nurses, AHPs and non-clinical staff. In the community too, we see huge variations in staffing and productivity, with significant differences in approach and delivery between community providers leading to very different patient access and experience across geographies.

We have staffing ladders, demand and capacity tools, and productivity approaches that can all help the NHS plan its workforce better – but only if we also get the transparency, processes and culture right.

It’s the how that kills you

This is not radical or impossible. Many of these approaches are increasingly being looked at by leading trusts in England to organise their staffing most effectively.

But it is hard – particularly when it is not part of an organisations existing ways of working. The challenge is in changing behaviours – and this requires a change in people’s context – messaging, tools, incentives and consequences.

In the matter of more effectively managing workforce, we have found three levers for changing context are key:

1. Data transparency: Data is the bedrock of effective workforce management. Having the right data allows you to have the right conversations – about service demand, about productivity, about priorities, and about resourcing. Data needs to be robust, understandable, and comparable. National dashboards are helpful here – but there is a need for local data combined with the right insights so you can see the “how” as well as the “what”.

But data on its own is not enough. The data needs to be combined with a transparency on the benefits that matter to staff – be it clearing backlogs, reducing clinic overruns, more time to train and faster access to care for patients.

2. Leadership: Workforce management is not a simple process. Too often, it is delegated down an organisation, with insufficient guidance or support. Leaders – and in particular medical directors and chief nursing officers have a key role here – have to be visible, prioritise workforce management, support their divisional and operational managers – and to put the time into having the right (and sometimes hard) conversations.

3. Accountability and Empowerment: Workforce management should not be a one-off exercise. Transparency in workforce resourcing, activity and focus should be a regular conversation, and all staff should be able to understand how they are delivering against their goals. But it is important that this is set within the right context. Staff need to have the tools and support to help them manage and deliver properly. There also needs to be positive consequences – staff should be rewarded for achieving their goals.

With the right data transparency, the right leadership, and the right accountability and empowerment, we have seen that is possible to set the context for improved performance and better outcomes – turning disempowerment into engagement.

Getting this wrong is not an option

The workforce is the bedrock of the healthcare system. Despite the growth in total workforce numbers, the NHS is not awash with resource, and remains in a fragile state. Getting the right staffing empowered to work in the right way is critical for the long-term sustainability of the NHS.

The good news is that this is possible. Supported by proactive and engaged leadership, we have seen trusts deliver rapid improvement in both their workforce productivity and satisfaction, built from approaches that change the context for staff by prioritising transparency, empowerment and accountability.

The prize is there – there is not a trust or integrated care system in the country that would not wish to reduce clinical variation, support their frontline staff to see more patients and improve utilisation – but it needs an approach embedded in a clear theory of change based on the three principles outlined above. This gives us the opportunity to enable transformation – and return us to a more sustainable way of working that is better for staff, and patients.