A car manufacturer’s success in matching workforce supply to business demand has lessons that the NHS should learn quickly.

In the wake of recession, European car makers are scrambling to restructure or consolidate in response to over four years of falling demand and profits.

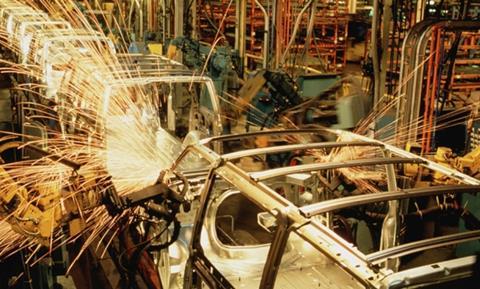

A little earlier this year, with declining sales and many of its factories running at partial capacity, General Motors agreed to a new workforce deal that means the Vauxhall car plant in Ellesmere Port will survive and its sister factory in Germany is likely to close.

A visionary proposal from management, staff and the union Unite tipped the balance in favour of a UK deal. An extra third production shift will be added at the Vauxhall factory to ensure 24-hour a day running, along with an agreement to introduce weekend working to guarantee the plant works at full capacity.

The workforce agreed a four-year pay deal, including a pay freeze for two years, followed by rises of around 3 per cent in years three and four based on increased productivity and market share.

More complex than cars

What can the NHS and particularly provider side leaders and managers learn from this? I can hear the siren voices already trotting out the line that this is comparing apples and pears and that delivering healthcare is far more complex than making cars.

Well yes, there probably is something in that argument but let’s be honest, it is a basic truth that workforce planning in the NHS has lacked rigour in matching clinical and general workforce supply to the ever-changing demand for a variety of healthcare and service needs.

We spend billions on healthcare each year and on average, close to 60 percent of that is spent on the clinical workforce, who provide patient care. Yet we are comparatively ineffective in estimating workforce needs accurately, or developing strategies at service or organisational level that dynamically keep supply and demand in balance.

This can often lead to suboptimal patient care, poor control of workforce costs and can also make service delivery inefficient.

This is the last place to be in a world of continuing austerity, with a number one priority to deliver on the QIPP mantra of providing high-quality, accessible, cost-effective care. Hackneyed though the phrase is, this really does mean that we need to have the right number of the right clinicians in the right places, like clockwork, every time.

Workforce planning in the NHS has traditionally been difficult because of the long lead times associated with changes to the workforce profile. Part of the reason for this is the oil tanker nature of professional education and training which never moves as quickly as the market does.

The workforce supply struggle

Furthermore, for a variety of political, professional and bureaucratic reasons, NHS trusts - foundations or not - have largely struggled to effectively match the ebb and flow of service demand to workforce supply.

No-one doubts that complex workforce planning is an inexact science - after all, it’s not that long ago that a decade-old planning decision to raise medical school enrolment by 50 per cent resulted in an over-recruitment of trainees for some specialist training. This leads to a second problem; an excess of qualified doctors in certain specialties. Because the NHS generally guarantees doctors employment for life, it has no easy way to eliminate the excess.

One consequence of this is to accept that, as in every other area of life we will never be able to forecast future needs perfectly. In practice this means that NHS organisations are going to need to work together and independently to be more in tune with the labour market and to respond to trends over shorter time frames. They will almost certainly also have to introduce much greater flexibility into their workforces.

Contentious nationally driven policies to differentiate workforce terms and conditions between different regions of the country, together with local innovation from trusts, are likely to aid this process.

Additionally, all over the NHS workforce flexibility is being improved by enhancing the skills and capabilities of health professionals who are not doctors. Refocusing the roles of specialist nurses, the deployment of nurse practitioners and physician assistants has broadened considerably in recent years. As the demand for high-quality outcomes of care ratchets up, it is likely that the demand for specialist services will be concentrated in fewer, larger centres of excellence and demand for routine services now provided by hospitals will increasingly be localised

Learning from Ellesmere

It’s not rocket science to assume therefore, that both legally and professionally the scope of practice for non-medical professionals will expand even more rapidly. What is safe and appropriate for nurse practitioners and physician assistants to do will vary, but because these health professionals can be trained much more rapidly than doctors they can offer an especially attractive way to increase workforce flexibility.

In this scenario, I would venture to suggest that there is a lot to learn from the Ellesmere Port car plant and its battle to win a future in a tough market environment. The path ahead for all trusts involves tough decisions about how to radically change the roles of professionals, control the pay bill and make the workforce super lean while flexing staff up and down in response to quality, service and environmental demands.

I would argue that an ability to combine strategy and agility in delivering workforce change is likely to be the single most important factor between success and failure in the years ahead. Any trust that does not take steps to tackle this challenge now is likely to find itself unable to manage almost two-thirds of its spending effectively.

Stephen Eames is chief executive of The Mid Yorkshire Hospitals Trust.

No comments yet