As the focus on NHS transformation intensifies, enabling bottom-up change is key, writes Jennifer Trueland

Top chiefs cropped

It starts with a provocation. NHS Improving Quality’s recent white paper says right upfront that “this is a time for radical change in health and care systems” and challenges leaders to open their minds to how this is achieved.

But change means different things to different people. On the frontline it can sound like a threat rather than an opportunity to do things better.

And at a time when the health service is struggling to cope with winter pressures, does anyone have the space to step back and think about change?

Challenge Top-Down Change

A different look

According to Steve Fairman, the managing director of NHS Improving Quality, this is precisely the time to take a fresh look at change, which is why he was keen to launch a campaign with HSJ and Nursing Times to challenge top-down change this month.

“I don’t think it could have been planned better,” he says. “There will be people who will look at this and say ‘what are they on about? We don’t have time for this’, but there will be other people who will realise that every movement has to start somewhere, so when is better than now?”

Mr Fairman believes that the climate is right to achieve the change that he, and others, believe health services desperately need. He was delighted when the NHS Five Year Forward View was published in October , articulating why change is needed, what change might look like, and how it can be achieved, because it chimed so well with the NHS Improving Quality white paper The New Era of Thinking and Practice in Change and Transformation.

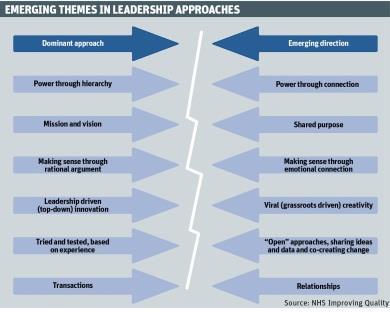

Published in July last year, this examines trends in change and transformation from multiple industries across the world, and makes it clear that change needs to happen faster, and become more disruptive.

“Change is changing,” he says simply. “It’s not enough to do change in the way we’ve always done it. NHS organisations are no longer isolated; they are part of a complicated system. For patients, there’s a single pathway of care, but lots of organisations are involved in this one pathway, which means we have to engage everybody.”

Forcing people to change by either carrot or stick won’t work, he adds. “You can’t just make people change; you can’t say ‘change and you’ll get more money’ or ‘don’t change and you’ll lose money’. People need to understand the benefits of change, not just the how, but the why.”

Make bottom-up the norm

NHS Improving Quality’s recent paper is aimed squarely at people who have the power to make change happen but it wants them to create the environment where bottom-up change becomes the norm. “What we’re saying to leaders is: are you up to the challenge because change starts with you. You can’t expect people to change if you don’t.”

Samantha Jones, chief executive of West Hertfordshire Hospitals Trust, admits that she has the same autocratic and hierarchical feelings as most of us, certainly those in traditional leadership roles.

But she recognises the importance of putting these natural impulses aside, and creating an atmosphere where any member of staff (or indeed, patient or carer) is listened to, and heard, in a meaningful way.

Her trust has the well regarded Onion project, set up as a daily forum to “peel back the layers” of issues with a focus on patient safety and continual improvement.

Those who attend, including the executive team, are open to hearing about what could be done differently today to make a difference for patients tomorrow, and everyone who raises an issue is asked for a solution to address it.

NHS Change Day

NHS Change Day started in 2013, and this year will take place on 11 March. The idea in the first two years was to encourage staff to remember why they had joined the NHS in the first place, and to give pledges for change.

NHS Improving Quality managing director Steve Fairman made a pledge in 2014 that involved learning more about what happens in frontline primary care. He said: “I made a reciprocal pledge. I said I would shadow a GP on the condition that a GP shadowed me. I had a great time - I went on home visits, spent a lot of time talking to staff, I was on reception for three-quarters of an hour.”

So did anything surprise him? On the one hand, he was a little shocked by how much was still done on paper due to “archaic” systems.

But Mr Fairman adds: “I was really impressed by the fantastic level of knowledge that everyone had about the people who walked through the door; the staff knew the patients and were able to ask them about their lives and their families.

He admits he was a bit apprehensive when the GP came to shadow him in return in case it looked like his job was “boring”. “I made a point of taking him to some interesting meetings so that he got to see decision making in action quite near the top of the NHS. I think he saw that people [in meetings] really care, and that there are real debates over decisions and that people want the best for patients.”

This year the aim is to ask people to talk about change they have already started.

More information, including how to take part, can be found at changeday.nhs.uk

Change is about people

While obviously an advocate of enabling bottom-up change, she is just as clearly a believer in finding the right language. “The concern that I have is that we’re very good at saying the NHS needs to change. We’re not so good at saying that there are areas where we are good and other areas where we’re not so good - change for change’s sake isn’t the answer,” she says.

“If I talk to clinical managers and ask them what’s going well, and what we need to do to make things better, then we can have a conversation. If I say ‘right, we’ve got to change’ they’ll just laugh at me.”

Ms Jones believes that change is about people and says that you have to trust and value clinicians to make the right change happen in their particular area. That means breaking it down to ward level or whatever else seems appropriate.

“When I was a staff nurse on a ward many years ago I could just about see what needed to happen on that ward. Some people need to take global change forward but it needs to be adapted and translated to make it meaningful for them.”

The messages are too often “do more, faster,” she says, but there has to be a way of engaging all grades of staff and others, from admin to non-executives, and talking in a way that makes sense to them.

To take her trust as an example, like many others, it has been “challenged”, she says, with significant governance risks and other issues to tackle.

‘People need to understand the benefits of change, not just the how, but the why’

Communicating the trust’s values and purpose to everyone involved - so that they really understand, and want to make improvement happen - is key.

“I can see all that but unless we can make sure that 4,000 staff think its worth getting out of bed for then there’s no point,” she says. “The more engagement, the better as far as I’m concerned.”

Ms Jones uses Twitter to communicate with staff and patients, and believes that all routes should be exploited to ensure that everyone is involved meaningfully in the work of the trust.

Although social media is important, it is not enough, she says. Her trust involved more than 600 members of staff and patients who volunteered to help create the trust’s values and behaviours. “We’ve got patients and staff side on every committee and every interview panel,” she adds.

Ms Jones concedes that it is challenging to find the time for staff to think about change, let alone make it happen. But for her it is not about coping with challenges like austerity and winter pressures, it is about ensuring sustainability. “If we’ve got 100 per cent bed occupancy, how do we give people the space to do it and still do the job we need them to do,” she asks.

Part of this is creating an environment where people feel they have “permission” (within the rules) to implement change, and making sure that those who want to do so have the right support, she says.

This helps to build an atmosphere where creativity and a constant striving for improvement are valued. “Some of my staff would say they’re not allowed to do anything [about change],” she says ruefully.

Taking the time

Mr Fairman recognises the challenge of freeing up staff to become agents of change; indeed, it is one that he has grappled with at NHS Improving Quality. He has set up an internal team of people whose job it is to be innovative - disruptive even - and who have been released from their corporate responsibilities to allow them to do this. “Not everyone saw the value in that,” he says candidly.

‘We’re very good at saying the NHS needs to change, but change for change’s sake isn’t the answer’

“But it’s about the way that leaders deal with organisations. I can see that if I’ve got someone working in [accident and emergency], it’s going to be difficult to find the time to let them think about how things could be done better in their area. But they are the people who know what needs to happen. Leaders have to have the courage to do this. If I didn’t do it in my organisation, how could I ask other leaders to do it in theirs?”

He is quite sure this idea will not come as a revelation to some healthcare bodies. “I’m certain that there are organisations in the NHS doing this already,” he says. “There are well performing trusts providing great services and they will have lots of improvement experts. That gives us models we can look at.”

Change as a movement

Real leaders recognise that continuous improvement cannot be achieved if the focus is maintaining the status quo, he says. But equally, it is important to recognise the value that different perspectives can bring, particularly if you can involve people who are passionate about a particular area of service.

‘Unless we can make sure that 4,000 staff think its worth getting out of bed for then there’s no point’

In that way, change can become a movement. Mr Fairman cites a national campaign to improve wheelchair services. “These are poor in a number of places, and there have been about 10 reports into the issues, but very little has changed,” he says.

Initially, the campaign involved asking for volunteers, which brought together a committed group of people who had particular skills and expertise, including people who were wheelchair users or who had relatives who used wheelchairs, he says.

From pledge to project

The project is engaging as many wheelchair users as possible including campaigner and Paralympian Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson. Action included developing a digest to bring together evidence on what is working well and not so well, backed by comments from users, carers and campaigners.

The campaign was officially launched in November last year at a summit attended by users, carers, clinicians, third sector organisations and others. A social media campaign has also been launched using the Twitter hashtag #MyWheelchair.

This event built on the findings from a wheelchair summit held by NHS England in February last year, which looked at the problems with wheelchair services and tried to identify what should be done at a national and local level.

‘Never doubt that a small group of committed citizens can change the world; it’s the only thing that ever has’

“The spirit in the room [at the summits] was almost overwhelming,” says Mr Fairman. “We were tapping into people’s enthusiasm and experience, and it was amazing.”

The idea, he adds, came from the “social movement” NHS Change Day. “It was [former NHS chief executive Sir] David Nicholson’s Change Day pledge to make a difference to wheelchair services. It was his personal pledge, and he asked Ros Roughton [director of NHS Commissioning] to take it on.”

While not exactly coming from the grassroots, a pledge from the boss has a certain influence. The campaign showed what can happen when an individual sees something that needs to change and does something about it.

He quotes US cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, author of Coming of Age in Samoa. “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

2 Readers' comments