Collaboration between the NHS and higher education institutions is often hindered by differing perceived demands and values. Kate Springett and colleagues explain the tensions and why we must resolve differences

Surgeon/doctor, shaking hands with corporate person

Many UK-wide NHS documents reflect requirements for research education to enhance practice and improve patient care. They outline the benefits of research to patients and service delivery.

Managing this at the same time as providing an excellent service can be challenging.

‘Managing the benefits of research to patients and service delivery at the same time is challenging’

One route to increase research capacity is to boost collaborations between the NHS and higher education institutions (HEIs), particularly in developing the clinical academic careers of nurses, midwives and allied health professionals (NMAHPs).

The NMAHP clinical academic careers development group, initiated by the Department of Health and hosted by the Association of UK University Hospitals, comprises of NHS and HEI representatives, and aims to promote support for clinical academic career pathways for NMAHPs.

We knew anecdotally that there are some tensions for research collaboration between the NHS and HEIs.

- Making research nurses feel part of the team

- The new way for trusts to improve staff engagement

- Ready for researchers: modernising the NHS’s scientific workforce

Potential tensions

Through the Bristol Online Survey in November last year, sent out via the 31 members of the career development group, we enquired about the differing demands on HEIs and the health service. We asked about issues they were facing including efficiency of services, performance measures and value given to research activity.

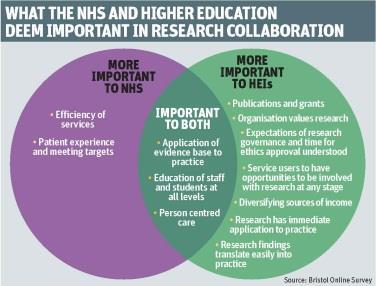

We received 323 responses. The NHS and HEIs agreed on the importance of evidence based practice, staff development, education of students and staff at all levels, and person centred care.

Performance measures, patient experience and meeting targets were also generally agreed, although they are seen as more important to the NHS than to HEIs.

Clear differences and potential tensions for the NHS and HEIs include:

- efficiency of services (very important to the NHS);

- grants and publications (very important to HEIs); and

- diversifying income (important to HEIs).

Responses from those in joint appointments indicate they have some further and different tensions.

The vast majority of respondents’ comments expressed frustration and even anger, but this was possibly not surprising as the survey focused questions on “tensions”. However, these pessimistic views were not universal.

NHS respondents spoke about the lack of time for research and the frequent lack of connection between senior management strategy and what happens on the ground.

There was also a sense that medical research was supported much more actively than for NMAHPs.

‘Respondents noted changes in attitudes and a step-change on the focus of research within trusts’

However, with some optimism for the future, respondents noted changes in attitudes and a step-change on the focus and standing of research within trusts.

These differences could explain the challenges HEI and NHS colleagues face in conducting research and in developing joint clinical academic posts. It appears important to acknowledge these differences and find ways to work around them as they are unlikely to go away.

The importance of research findings being easily translated into practice, and research being immediately applicable to practice were asked as separate questions.

It is curious that both issues were seen as less important to NHS respondents (42.7 per cent deemed it very important) than those in HEIs (62.5 per cent said it was very important) given the NHS focus on clinical practice.

Of the 323 respondents, 114 added comments. Many talked about the lack of time for research in the NHS because “immediate clinical work takes priority”, and that there was disconnect between senior management’s commitment to research.

They also highlighted what managers actually allow and value in clinical areas which leads to a “lack of infrastructure for research, lack of culture that values research activities, and a lack of support for nurses to engage in research activities”.

Some felt medically led studies were the only type of research supported.

Optimism about the future

There were relatively few comments from HEIs.

Some joint posts generally work well but with their own procedural tensions.

‘The immediacy to deliver on the NHS agenda often creates tension in HEIs’

One respondent said: “There are quite different tensions that I experience as an incumbent of a joint role, and between the two organisational cultures… The tension is where the grant is actually located in order to count in organisational metrics.”

Respondents noted “the immediacy to deliver on the NHS agenda is often a tension with the comparatively slower delivery in HEIs”.

There was some optimism about the future. One person wrote: “I am seeing some improvements with a modest, yet growing culture of clinical academia.”

Well founded fears

However, people expressed concern about re-integration into the workplace after completing a research course. They were also concerned that their hard work, new knowledge and acquired skills were largely wasted.

“It is essential to address the tensions for clinically based researchers between service delivery and clinically based research,” one respondent said.

Many felt that “in working with [National Institute for Health Research] funded projects early in their career, upon completion of their master’s or PhD no one in the trusts knew how to use their skills and expertise”.

The focus was placed on service delivery and this happened time and time again.

‘If we value evidence based practice, we must value the time and skills needed for it’

The anecdotal impression of tensions existing around research collaboration between the NHS and HEIs appear well founded.

We need to acknowledge these differences and the continuing pressures on service delivery as they are unlikely to go away. We need to adapt to find ways to work with and around these challenges.

Support for NMAHPs to attain and sustain research activity in the NHS needs to be part of every trust’s research strategy.

This support seems generally clear at board level, but responses indicate difficulty at the ever-pressurised clinical front line.

Research activities need to be integrated as an essential component of NMAHPs’ clinical practice.

When staff come back into clinical practice after research training, we need to harness their skills in addressing clinical problems.

We need to consider what can be gained from clinical academic posts – research to improve patient care and patient experiences, funding, implementation of evidence – rather than what is lost, such as less time in clinical practice.

If we value evidence based practice, we must value the time and skills needed for it.

One route to increase research capacity is to boost collaborations between the NHS and HEIs, particularly in developing the clinical academic careers of NMAHPs.

Find out more

- For full report of the Bristol Online Survey email Siobhan Fitzpatrick

- Read the Finch report

Kate Springett is professor and head of the School of Allied Health Professions at Canterbury Christ Church University; Christine Norton is Florence Nightingale Foundation chair of clinical nursing practice research at King’s College London; Sue Louth is North West AHP workforce lead for the North West Centre for Professional Workforce Development; Christi Deaton is a Florence Nightingale Foundation professor of clinical nursing research at University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine; and Annie Young is professor of nursing at the University of Warwick

No comments yet