Ali Raza, Vlad Kovach and Amanda Maunders make a case for kindling “non-clinical compassion” into healthcare policy thinking, citing examples of how Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation Trust is trying to integrate a compassionate outlook in non-clinical work

A reminder of the indispensability of compassion in healthcare

It is important to chart the history in order to remind ourselves of the importance of reconciling compassionate care with efficiency. This is no more evident than in the wake of the Francis Inquiry into Mid Staffordshire FT.

The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry Final Report (2010) highlights the fallout of pure “business style” management (Crawford et al., 2014) devoid of compassionate care.

Francis opines for “people to come before numbers” and for benchmarks to be used “as tools not ends in themselves” (Francis 2010, as cited by Crawford et al., 2014).

The Mid Staffs scandal issues an eternal lesson for leadership to strive to balance economic considerations of efficiency with ethical considerations of compassion.

The Department of Health and Social Care’s Compassion in Practice (2013) strategy sets out an essential framework for implementing compassion at an organisational level for nursing, midwifery and care staff.

Examples of “clinical compassion”

Clinical settings have a tendency to manifest the antagonism between compassion and efficiency. Consider for example the ethical regard for patient preferences, which underpins compassionate care, and how the respect for such preferences may need to override the cost implications of maintaining life saving treatment.

In the context of rationing caregiver time (Maxwell, 2009), the antagonism is framed as a conflict between the duties of fairly distributing clinical time and delivering attentive care proportionate to patient vulnerability (Maxwell, 2009). It is possible to align compassion and efficiency objectives.

Consider for example Anticipatory Care Planning, which supports an understanding of the wishes of patients (at risk of hospitalisation) in their care planning (Baker et al., 2012).

Clinical settings have a tendency to manifest the antagonism between compassion and efficiency

Baker et al. (2012) compared number of hospital admissions and occupied bed days between a cohort who received ACP against a control cohort, which did not receive ACP. The ACP cohort had significantly lower admission rates and occupied bed days post-intervention compared to the control cohort (Baker et al., 2012).

Leadership thinking should actively reflect on these “win-wins” as they represent the ultimate goal of policy making; to maximise the efficiency of care while enhancing quality.

The built environment; compassion from a non-clinical perspective

In our line of work in a non-clinical directorate delivering capital projects to Guy’s and St Thomas’ FT, compassion takes on an entirely different dimension. In this unique context, patient and staff preferences for new build aesthetics are given due consideration during the project life cycle, highlighting how we integrate a compassionate outlook in non-clinical work.

In Capital Development at Essentia, we have a dedicated stakeholder and engagement officer responsible for including patients in decision making for capital projects, supported by the trust’s overarching Patient Engagement Team.

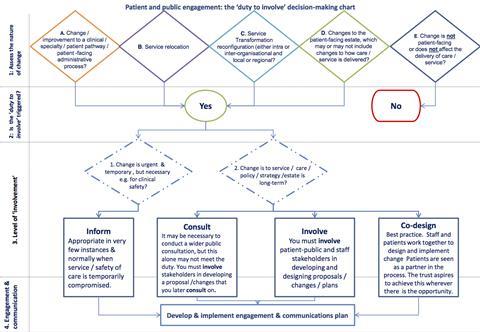

The Duty and Decision Making Chart (Diagram 1) (Putting Patients First: a policy for patient and public engagement and consultation, 2018), highlights the process designed to guide project teams for inclusion of patients in their projects.

The table shows the level of patient involvement across 23 live projects in 2017-18.

| Level of involvement of patients in capital projects in Essentia, 2017-18 [Data provided by Patient and Public Engagement (PPE) team, Guy’s and St Thomas’ FT] | |

|---|---|

| Level of involvement | Number of projects |

|

Inform |

2 |

|

Consult |

2 |

|

Involve |

6 |

|

Co-design |

13 |

This graded spectrum of patient inclusion reflects the reality that service changes can elicit a range of impacts upon patient care, and thus require appropriate levels of patient integration in project planning.

It also allows for competing values, such as patient safety, to take precedence where such values become paramount. This is how patients are both acknowledged and empowered as key stakeholders in the codesign of clinical spaces, examples of which are highlighted below.

The Guy’s Cancer Centre at Queen Mary’s Hospital Sidcup is a satellite service delivering treatment to our patients closer to home. During the design stage, a patient reference group was set up and chaired by a patient.

At Guy’s and St Thomas’ FT, patient and staff preferences for new build aesthetics are given due consideration during the project life cycle, to integrate a compassionate outlook in non-clinical work

The group was involved in developing design of the building and decisions about services delivered on site. The patients were actively involved in the development of the Dimbleby MacMillan Support Centre for cancer information and support, including its selection of artwork and furniture. The centre went operational in May 2017 and received, and still receives, positive feedback from patients.

Patients helped to develop the new Critical Care Strategy and to design the new Critical Care Unit at St Thomas’ Hospital. Patients provided feedback on certain design features and relatives were accorded an opportunity to input on the practicalities of the area, including access to information about local facilities, as they can spend many hours on the unit.

Taking this on board, patients and relatives were engaged in furniture selection and artwork for the interview and relatives’ rooms. The unit is due to go operational in early September 2018 and early indicators from site visits have all been very positive. Post-project feedback will be gathered during the first six months of occupation. Most importantly, patient and staff involvement helps ensure the facilities are fit for purpose when they come in to operational use.

Implications for policy drivers

It is all too easy to confine compassion to the clinical caregiver and patient context. Policy drivers such as Compassion in Practice (2013) focus primarily on this area, but a requirement exists for engendering “non-clinical compassion” into healthcare policy thinking, which is distinctly scant.

The piloting of “Always Events” (Compassion in Practice; Evidencing the Impact, 2016) in non-clinical pilot sites would exemplify this; a pilot of an Always Event in a department such as ours might include an audit of a sample of live projects to ensure that patients are always involved at the right level [guided by process (Diagram 1) and legal requirements], and may identify barriers to achieving this ideal.

History has a tendency to repeat itself. Lest we forget the episodes of the past, let us remain steadfast in our duty to empower our patients, but the commitment (and reward) for doing so must come from the top.

The authors would like to thank Amanda Maunders (stakeholder engagement officer at Essentia) for her support, and Andrea Carney and Fatimah Vali from the Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Foundation Trust Patient and Public Engagement (PPE) Team for their support and provision of data (table and diagram).

No comments yet