In the first of four articles analysing a survey of senior staff, Greg Pitcher reports on what motivates and demotivates the NHS’s chief executives - and the skills they feel are vital

This survey was produced in association with Hunter Healthcare

The NHS is the toughest yet most rewarding place to run an organisation, research has revealed.

A survey of 49 chief executives - run in association with recruitment firm Hunter Healthcare - found that, although 77 per cent regarded the health service as the toughest sector they had worked in, a similar proportion said it was the most enjoyable.

The results - part of a broader poll of 247 senior members of NHS staff - suggested that health chief executives thrive off challenges at work.

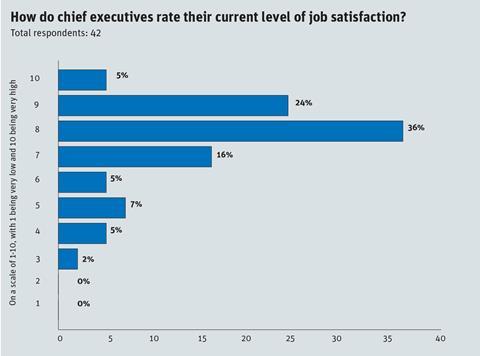

Almost two-thirds of chief executives in the health service rated their job satisfaction at eight out of 10 or higher (see below). This compared to fewer than half of the overall senior staff polled saying the same thing.

Sir Robert Naylor, chief executive of University College London Hospitals Foundation Trust and chair of the recent HSJ Future of NHS Leadership inquiry, said health service chief executives were a rare breed. “I think we are an extreme group in society,” he said. “There is a detailed selection process and I recognise the traits I display as consistent across chief executives at leading hospitals.

“They are challenging places to run but they are filled with highly motivated people with high IQs and excellent emotional intelligence”

“You have to be very committed - I work every hour I am awake, whether it be reading something or talking to someone. These are jobs for people who like challenges and having complex problems to solve.”

Making a difference to patients was cited by 86 per cent of chief executives as a reason for high job satisfaction. A similar proportion said their satisfaction rating was boosted by finding their work challenging and rewarding.

Fewer than one in two chief executives said their job satisfaction was boosted by their financial package, while fewer than one in three said the same about being supported by senior colleagues, the wider NHS or the public.

Sir Robert said chief executives could make more money for less onerous work by moving into the private sector. But people were still attracted to management careers at health service organisations in their droves, he pointed out.

“They are challenging places to run but they are filled with highly motivated people with high IQs and excellent emotional intelligence,” he said.

“It is very rewarding to help clinicians deliver care that makes a difference to people in incredible levels of physical and emotional distress.”

A high regulatory burden and external pressures were cited by 60 per cent and 58 per cent of organisation leaders respectively as negative pulls on job satisfaction.

External pressures and the burden of regulation remained the top two negative factors on job satisfaction when all senior NHS staff were questioned. However, they were cited as negative influences by fewer than half of respondents in each case, suggesting they weigh more heavily on chief executives than on other staff.

Sir Robert said recent legislation had ramped up the pressure on NHS chief executives.

“There is a huge process you have to follow so making change is really difficult,” he said. “If you have to make change to adapt to a new environment, but you are stopped by bureaucracy, then you have to be pretty powerful to drive that through.”

Revolving door hospitals

Mike Chitty, head of delivery at the NHS Leadership Academy, agreed that the conditions health service chief executives worked in were extreme.

“If you put people into jobs that are impossible to do - actually beyond the evolutionary capability of human beings - then you can only do so much to help with resilience before you have to give them a more humane environment,” he said.

But Mr Chitty questioned the wisdom of blaming external pressures for difficulties, saying they had to be accepted as part of the job. “Saying regulation is a burden is like a football manager blaming a referee,” he said. “You have to understand the real nature of the relationship between chief executives and regulators.”

Sir Robert said the constant churn of health secretaries and of chief executives themselves made the job very hard.

“It takes five years for a chief executive to make a difference but the average lifetime of a chief executive in a post is less than two years. You have revolving door hospitals.”

“Saying regulation is a burden is like a football manager blaming a referee”

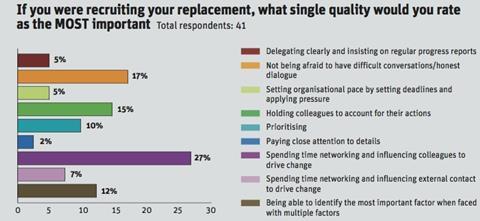

When health service chief executives were asked what skills were important for their job, a number of traditional management traits were given short shrift.

Prioritisation was selected as among the top three most important skills by 20 per cent; setting deadlines by 15 per cent; and close attention to detail by just 7 per cent.

Key skills

In contrast, people skills were highly valued, with 61 per cent choosing an ability to influence change as a top trait, and the same proportion selecting a willingness to have honest conversations.

The most important factor when recruiting a chief executive is ensuring the successful candidate can spend time networking with staff to drive change, according to the poll.

Sir Robert said the key focus of those at the top of NHS bodies should be to get the best people in and to get the most out of them. “I used to give a very detailed description of my job when I was asked about it at dinner parties,” he said. “Now I just say I do two things - motivation and reputation. I motivate my people and I worry about the reputation of the organisation to attract the best people.”

More than half of chief executives questioned said strong personal resilience was in the top three factors making them suitable for their job. Next on the list were an ability to inspire and a willingness to make decisions.

More than three in four chief executives described themselves as extroverts, with the remainder identifying as introverts.

The proportion of senior staff saying their workload was too high was greater than the proportion of chief executives.

But this sense of a “lighter” to-do list did not translate into lower stress levels for health leaders.

Finest leaders in the country

Just 18 per cent of senior staff described their jobs as “very stressful”, compared with 25 per cent of chief executives. As chief executive responses are included in the all-staff figures - in this case effectively dragging the former percentage up - this is a significant difference.

And chief executives seem to be less impacted by internal politics. Just 10 per cent said such matters got in the way of their work, compared to 25 per cent of senior staff in general.

Rob Webster, chief executive of the NHS Confederation, said the NHS had some of the finest leaders in the country. “These results show how rewarding and challenging roles are - as well as the negative impact of operating in a bureaucratic and complicated system,” he said.

“To be successful, the NHS must retain a generation of leaders who reflect the findings in the survey: leaders able to make tough choices and difficult decisions by being guided by their values; leaders who operate in a system and build partnerships; leaders who recognise that engaging staff at all levels is the only way to achieve good outcomes for patients.”

Downloads

What makes a top CEO

PDF, Size 1.13 mb

So what does it take to be a chief executive in the NHS?

The first of a four-part series analysing a survey of senior staff speaks to chief executives about their roles

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

So what does it take to be a chief executive in the NHS?

- 2

10 Readers' comments